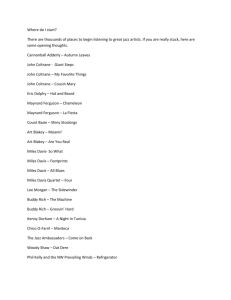

Abdullah, Luqman - eCommons@Cornell

advertisement