Tense and Reality - New York University

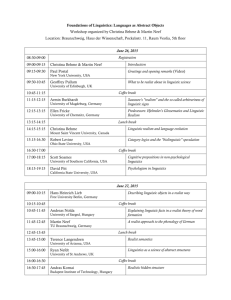

advertisement