opinion - Wall Street Journal

advertisement

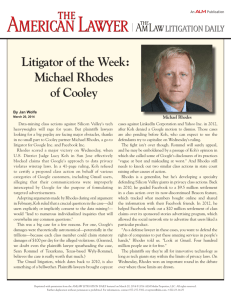

P2JW025000-0-A01100-1--------XA THE WALL STREET JOURNAL. Monday, January 25, 2016 | A11 OPINION Rhodes Must Not Fall W h i l e American universities cave to demands INFORMATION for “safe spaces,” AGE Oxford By L. Gordon UniverCrovitz sity issued an ultimatum demanding intellectual freedom. Chancellor Chris Patten this month told students to open themselves to challenging ideas or “think about being educated elsewhere.” Mr. Patten was answering demands that the university expunge its history with Cecil Rhodes, including removing a statue of its imperialist graduate and benefactor. Rhodes scholars last year insisted that their traditional dinner toast at Oxford to the founder—whose largess pays each student’s $100,000 in annual education expenses— exclude his name. “That focus on Rhodes is unfortunate, but it’s an example of what’s happening on American campuses and British campuses,” Mr. Patten told the BBC. “One of the points of a university, which is not to tolerate intolerance— to engage in free inquiry and debate—is being denied. People have to face up to facts in history which they don’t like and talk about them and debate them.” Mr. Patten, the last British governor of Hong Kong, is recalled fondly there for bolstering local freedoms. “You go to China, where they are not allowed to talk about Western values, which I regard as global values,” he said in the BBC interview. “No, it’s not the way a university should operate.” The “Rhodes Must Fall” movement wants to eliminate memories of a man the students say offends them. A true understanding of Rhodes acknowledges that the beliefs of his time differ from ours but recognizes that his ideals, including on racial issues, put him ahead of his times. This will outrage some of my fellow Rhodes scholars, but Rhodes should be celebrated, not vilified, for his imperial values. Soon after leaving England in 1870 for Africa, the 24-year-old Rhodes surprised dinner guests in a remote diamond-mining town by declaring: “Gentlemen, the object of which I intend to devote my life is the defense and extension of the British Empire.” He said the empire stood for “the protection of all the inhabitants of a country in life, liberty, property, fair play and happiness and is the greatest platform the world has ever seen for these purposes and for human enjoyment.” He aimed to promote ideals of liberty—common law, property rights and representative government. By his 30s, Rhodes was a mining magnate and prime minister of the Cape Colony, proudly expanding Queen Victoria’s realm. “We are the finest race in the world,” he said, “and the more of the world we inhabit, the better it Oxford’s sensitive students demand a statue’s removal. Time to stand firm. is for the human race.” In the 1988 Rhodes biography “The Founder,” Robert Rotberg concluded: “For him, England was both mighty and right. It was obligated to extend its grasp . . . to make the world a better, purer place.” The Cape Colony under Rhodes was liberal for its day. Africans could vote if they met the same property-holding or income requirements as whites. Rhodes might have bent too far to placate the Boers, the Dutch settlers whose support he needed to rule the colony. But at the end of his political career, Rhodes opposed a Boer plan to submit Africans to a literacy test before they could vote. Only after Rhodes left office did the Boers establish apartheid as official policy. When Rhodes created his scholarship in 1902, he in- cluded a clause far ahead of its time. His will specifies that no student will be “qualified or disqualified on account of his race or religious opinions.” The first black Rhodes Scholar, Alain Locke, was elected in 1907. Locke’s American peers shunned him; some threatened to resign their scholarships in protest. An official history of the scholarship explains why the Rhodes trustees rejected the complaints: “There was plenty of ‘color’ in the British Empire,” they said, and no one “was going to be debarred from a Rhodes scholarship on that ground.” Locke became a leading writer and scholar. Instead of trying to erase Rhodes, Nelson Mandela embraced him. In 2002 the South African statesman posed for a photo in Cape Town beside a portrait of Rhodes. Mandela wagged a finger at him and said: “Cecil, now you and I are going to work together.” The Mandela-Rhodes Foundation funds education for Africans. “Combining our name with that of Cecil Rhodes in this initiative is to sign the closing of the circle and the coming together of two strands of our history,” Mandela said. Rhodes must not fall. He put his wealth behind the optimistic conviction that free inquiry would make the world a better place, expanding an empire of liberty. For that he deserves to be remembered— and toasted. Cuba’s Democrats Need U.S. Support Miami Cuban dissident leader Antonio Rodiles has been harassed, AMERICAS beaten, imprisoned and By Mary may have Anastasia been injected O’Grady with a foreign substance— more on that in a minute—by Castro goons. Yet he is calm and unwavering: “They are not going to stop us,” Mr. Rodiles recently told me over lunch here with his wife, Ailer González. Soviet-style Cuban intelligence is trained to crush the spirit of the nonconformist. Yet the cerebral Mr. Rodiles was cool and analytical as he described the challenges faced by the opposition since President Obama, with support from Pope Francis, announced a U.S. rapprochement with Castro’s military dictatorship in December 2014. One of the “worst aspects of the new agenda,” Mr. Rodiles told me matter-of-factly, “is that it sends a signal that the regime is the legitimate political actor” for the country’s future. Foreigners “read that it is better to have a good relationship with the regime—and not with the opposition—because those are the people that are going to have the power— political and economic.” The Cuban opposition is treated as superfluous in this new reality. U.S. politicians vis- iting the island used to meet with dissidents. Now, Mr. Rodiles says, “contact is almost zero.” When the U.S. reopened its embassy in Havana last year it refused to invite important dissidents like Mr. Rodiles or even Berta Soler, the leader of the Ladies in White, to the ceremony. Mr. Rodiles said the mission of pro-democratic Cubans is critical and urgent: “We need to change the message,” making it clear that the regime is “not the future of Cuba.” And this, he says, is the defining moment. If the Castros hope to transfer power to the next generation—be it to Raúl’s son Alejandro or a Cuban Tom Hagen—as Russia’s KGB forced Boris Yeltsin to yield to KGB veteran Vladimir Putin, they need to do it soon. Yet at the same time, Mr. Rodiles says, “if they give the country to their families in the condition it is in right now, it will be like handing them a time bomb” about to go off. That’s why, he tells me, this is a unique opportunity for freedom to emerge: The odds of successfully passing the baton in the current economic meltdown are low. Or at least they would be if Mr. Obama were not offering the regime legitimacy and U.S. greenbacks while refusing to officially recognize the opposition. Mr. Rodiles has a master’s degree in physics from Mexico’s Autonomous National University and a master’s degree in mathematics from Florida State University. The 43year-old returned to Cuba in 2010 and is a founder of Estado de SATS, a project to “create a space for open debate and pluralism of thought.” Obama has helped the dictatorship but ignored the dissidents. The police state views this as dangerous and has come down hard on the couple. Amnesty International was among those that called for his release when he was jailed in 2012 for 19 days. In July a state-security agent punched him in the face while his hands were cuffed behind his back. On Jan. 10 he and Ms. González, along with other government critics, were again attacked by a rent-a-mob on the streets of Havana. This time they were left with what looks like identical needle marks on their skin. Those wounds are worrisome. More than once the former leader of the Ladies in White, Laura Pollán, was left with open wounds after being clawed and scratched by plainclothes government enforcers. After one such incident in 2011 she mysteriously fell ill and died in the hospital. The government immediately cremated her body and the dissident community has long suspected that she was intentionally infected with a fatal virus by the regime. Under normal circumstances, the Castro family would have reason to fear the future. Totalitarian regimes collapse, Mr. Rodiles reminds me, “when the people inside the system, not just the elite, but the people who are in the middle, the ones who sustain the system, start to go and look for another possibility.” They do this because they recognize the future is elsewhere so they “move or at least they no longer cooperate.” Today young Cubans are looking for that alternative. The regime’s promise to Mr. Obama of economic opportunity and growth through small-business startups is a farce because the Castro family operates like a mafia, “and always has,” says Mr. Rodiles. To do well in the current environment the young have to join the system, or else they flee. Those who join are not ideological but only seek power. “If we can show that we are the ones with the power to transform the country, then these people for sure are going to prefer to be with us.” Failure is unthinkable for Mr. Rodiles. “We cannot allow the transfer of power because if they transfer the power, we can have these people for the next 20 or 30 years.” Write to O’Grady@wsj.com. Trump Laid Out His Playbook 30 Years Ago By Ben Jenkins D onald Trump’s six-month stay atop the Republican presidential field has confounded political pros. Rather than follow the playbook that has long guided campaigns through the arduous primary calendar, the bombastic billionaire is charting his own path, filled with insults and vainglorious preening that theoretically shouldn’t attract voters. But Mr. Trump laid out how he would run his campaign 30 years ago in his best seller “The Art of the Deal.” Perhaps if more strategists had read the book, this race would be tighter. So let’s parse what Mr. Trump wrote. “I play to people’s fantasies” and a “little hyperbole never hurts.” Mr. Trump has proposed a 2,000-mile-long wall at the Mexican border, a “deportation force” to expel an estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants, and a ban on all noncitizen Muslims entering the country. Those pledges represent the extreme wish-list items of Mr. Trump’s most ardent fans. They are also completely unrealistic. But Trump supporters say they like him for two reasons: He isn’t afraid to tell it like it is, and he isn’t a prisoner to political correctness. He is an outlet for the hyperbolic fantasies of voters who believe that the economy and politicians are leaving them behind. His presidential campaign is ‘The Art of the Deal’ in action. Back to the playbook: “Sometimes, part of making a deal is denigrating your competition.” Mr. Trump’s campaign has been marked by personal insults that any other politician would shun—or that would get him shunned. He has derided former Hewlett-Packard executive Carly Fiorina’s looks; mocked the energy level of former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush; and insinuated worse about Fox News’s Megyn Kelly. Mr. Trump claims to be good to those who treat him well, but his reaction to criticism is nuclear. The more outlandish his assaults on anyone who challenges him, the more voters seem to like it. He doesn’t mind alienating people along the way. Another Trump mantra: “Controversy, in short, sells.” The media feed on controversy and Mr. Trump knows it better than any other candidate. Even harsh stories that hurt him personally can be valuable professionally. Which brings us to: “Good publicity is preferable to bad, but from a bottom-line perspective, bad publicity is sometimes better than no publicity at all.” In his business life, controversy is a theme. He’s happy to play the media to inflame that controversy—it can be good for business, helping him leverage lower prices for whatever he’s trying to buy. In politics, his love for controversy has bought him more media attention than other candidates could dream of. And then: “I like making deals, preferably big deals. That’s how I get my kicks.” The Trump campaign style has the freewheeling feel of a reality-TV show, and he’s getting plenty of kicks from addressing big crowds that have waited in line hours to see him. The deals that Mr. Trump closes, whether for Manhattan real estate or votes in Iowa and New Hampshire, are how he keeps score. Finally: “If you ask me exactly what the deals . . . all add up to in the end, I’m not sure I have a very good answer. Except that I’ve had a very good time making them.” Given the scantiness of his policy proposals and seeming indifference to the details of governance, it’s not exactly clear what it all adds up to or why Mr. Trump wants to be president. But he is clearly having a very good time along the way. Mr. Jenkins is a Republican strategist and a principal at the Locust Street Group, a publicaffairs firm in Washington, D.C. BOOKSHELF | By Matthew Rees Advice From the Anti-Steve Jobs A Passion for Leadership By Robert M. Gates (Knopf, 239 pages, $27.95) I t has become almost a ritual of American politics to ask officeholders and candidates to disclose what books they happen to be reading. The titles they offer can seem like political posturing even if, by chance, they are not. In 2014 Hillary Clinton told the New York Times that Maya Angelou’s “Mom & Me & Mom” was on her nightstand and John McCain’s “Faith of My Fathers” on her bookshelf. At the moment, more than one candidate may be (discreetly) thumbing through “The Art of the Deal.” But the book they should all admit to reading—and actually read—is “A Passion for Leadership” by Robert M. Gates. Mr. Gates is best known as secretary of defense, first under George W. Bush (replacing Donald Rumsfeld) and then under Barack Obama (until 2011). But his public service began in the 1960s, and in the intervening years he worked in several senior posts, including a stint as CIA director under George H.W. Bush. Drawing on his own experience and his observations of others at the highest echelons of power, Mr. Gates has compiled a list of recommendations for leaders of all sorts— from Boy Scout troop leader to branch manager to corporate CEO to cabinet secretary—with a special emphasis on the challenges of guiding a large organization. Many of Mr. Gates’s recommendations are common sense (as he acknowledges): set deadlines, don’t micromanage change, empower subordinates, cooperate with the media, be prepared to act alone. As obvious as such advice may seem, it bears repeating because it is so routinely ignored. Among the more surprising suggestions: Don’t focus on reorganizing staff or structure, since it is distracting to the organization; be wary of consensus (which “inevitably yields the lowest common denominator”); and set short deadlines (doing so will “focus attention on an effort and signal its importance, creating momentum”). Confronted with President Obama’s wish to end the ban on openly gay people serving in the military, Mr. Gates describes how he set up a task force, which surveyed 400,000 service members and 150,000 service spouses, and held multiple focus-group meetings. “The review group paved the way for successful incorporation of the biggest personnel policy change in the U.S. military since women were brought into the ranks in significant numbers,” he writes. Among the keys to success in this case, he says, were inclusiveness and open internal debate. Gates preaches the value of civility and of worklife balance. While heading the Pentagon, he says, he never went to the office on a Saturday. The same principles applied when he was faced with cutting dozens of major defense programs. Believing that leaks would undermine his proposals, he “led an intensive consultative process” with military and civilian leaders and asked all participants to sign a nondisclosure agreement. In the end, Congress didn’t block his proposals, which he attributes to getting “buy-in” from the senior officials who were consulted. Befitting the only cabinet official to serve in both the Bush and Obama administrations, “A Passion for Leadership” is refreshingly nonideological. Implicit in his recommendations is that there is no “Republican” or “Democratic” way of leading. Indeed, there is as much in the book for Mrs. Clinton as there is for Donald Trump. Mr. Gates appears to be the polar opposite of the leader who has been deified in recent years: the late Apple founder Steve Jobs. Where Jobs was often a petty tyrant who prized secrecy, Mr. Gates preaches the value of civility, internal transparency and work-life balance. (He boasts that, while heading the Pentagon, he never went to the office on a Saturday.) He praises the CEO of Starbucks, Howard Schultz, for communicating with all the company’s employees on strategy, culture and performance. But there are fewer compliments than criticisms in “A Passion for Leadership.” Mr. Gates indicts many of those charged with overseeing major institutions—Congress, universities, corporations—for their parochialism and short-term outlook. He asserts that, in the public sector, leaders “vary dramatically in expertise, diligence, understanding, and just plain smarts,” adding that many “haven’t got a clue about how to run anything.” Mr. Gates unloads on the former Republican governor of Texas (and two-time presidential candidate) Rick Perry. Mr. Gates recounts that, upon his being offered the presidency of Texas A&M, Gov. Perry privately pressured him to withdraw. (Mr. Perry had reportedly promised the job to former Texas senator and A&M professor Phil Gramm.) Mr. Gates stood firm and served at A&M in 2002-06 but says that he and Mr. Perry had an “adversarial relationship” for his entire tenure. “The governor was a pain in the neck.” But Mr. Gates kept his feelings about Mr. Perry private and emphasizes throughout the book that, in general, it behooves leaders to schmooze with the governing class, since small deeds can pay lasting dividends. He once wrote a letter to the Washington Post defending Sen. Robert Byrd following a critical editorial. “This small gesture,” he writes, “made Byrd my friend and personal ally on the Hill” when he was CIA director and, later, at the Pentagon. While Mr. Gates’s book may persuade some readers to take the rudiments of authority and command more seriously than before and even pursue leadership training— part of the multi-billion-dollar “leadership industry”—Mr. Gates notes that his only formal training came in 1959, when he attended a program sponsored by the Boy Scouts, an organization he now heads. He is skeptical that leadership qualities—such as devotion to duty, sincerity, fairness and good cheer—can be taught in a classroom. “How can any training program inculcate personal character and honor?” When it comes to office holders and office seekers, questions of character may be even more important than their reading lists. Mr. Rees, who served in the Bush administration in 2001-05, is president of the speechwriting firm Geonomica and a senior fellow at Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business.