MARKETING

Too many ad hoc pricing decisions

Key determinants: consumption expandability and brand equity

Consider competitors and channels last

ACKAGED GOODS COMPANIES have long recognized that pricing is a key

P

lever in managing brands for profitability. Even so, pricing is so

underleveraged in practice that improving price management can raise

margins by as much as 5 percent. Companies seeking to capture this potential

must not only make eƒforts to understand the behavior of consumers but also

find ways to apply this understanding to the thousands of front-line pricing

decisions they make every year.

This opportunity exists because of a widespread assumption that marketing

departments set prices and make them eƒfective. Yet any consumer’s shopping

experience will demonstrate that this is a misconception.

116

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1998 NUMBER 3

TELEGRAPH COLOUR LIBRARY

K. K. S. Davey

Andy Childs

Stephen J. Carlotti, Jr

Not long ago, an acquaintance bought a box of cereal for $3.79. He was

unhappy because he had paid $2.49 for the same brand in the same

supermarket just two weeks earlier, when he had also used a 75¢ coupon to

pay a net price of $1.74. To add insult to injury, he knew that a nearby

supermarket always sold this brand for $2.99. These variations in price

confused him. In fact, they are entirely normal, and centralized pricing

decisions are responsible for very few of them.

K. K. Davey is a consultant and Andy Childs is a former consultant in McKinsey’s New Jersey

oƒfice; Steve Carlotti is a principal in the Chicago oƒfice. Copyright © 1998 McKinsey &

Company. All rights reserved.

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1998 NUMBER 3

117

WHY YOUR PRICE BAND IS WIDER THAN IT SHOULD BE

In category aƒter category, the end prices consumers pay for the same goods

vary widely. Some variations result from promotions by manufacturers, such

as temporary price cuts, circular ads, coupon ads, end-of-aisle displays, preprice packs, and bonus packs. Within a channel, prices vary as a result of

retailers’ pricing and promotion strategies, such as EDLP or hi-lo,* doublecouponing (the process by which a retailer oƒfers to double the face value of

a manufacturer’s coupon for shoppers in its stores), and loyalty cards. In

addition, prices vary from channel to channel because of diƒferent value

propositions: convenience at a higher price or less variety and service at a

lower price, for instance. These variations apart, consumers themselves adjust

pricing by responding to consumer promotions, notably free-standing inserts,

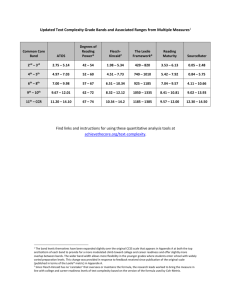

checkout coupons, and onExhibit 1

pack coupons. We call this

Consumer price bands

range of prices for an SKU

Example: Cereal

Weeks in store Units bought (stock-keeping unit) within a

at

each

price,

at

each

price,

Any promo price

percent

percent

market the consumer price

1.0%

$1.00–1.49 0.1%

Range band (Exhibit 1).

of prices 3.8

1.50–1.99

paid by consumers 2.00–2.19

1.1

2.20–2.39

1.4

27.5

5.7

At most packaged goods companies, the complex decisions

3.3

6.8

2.40–2.59

about list prices, trade pro2.0

2.60–2.79 1.5

motions, and consumer pro3.4

3.6

2.80–2.99

motions that drive the con1.2

3.00–3.19 1.6

sumer price band are made

10.6

6.1

3.20–3.39

19.9

13.9

3.40–3.59

by several diƒferent internal

16.4

10.1

3.60–3.79

organizations, each inspired

17.0

9.6

3.80–3.99

by its own goals or definitions

19.0

8.7

4.00–4.49

of success. Prices controlled

0.9

>4.50 0.5

centrally by senior management reflect a company’s revenue and profit aspirations, the level of inflation, and competitive pressures.

Trade promotion budgets are determined at the account level by salesforces,

and oƒten come into play to meet short-term volume targets. Consumer

promotions, on the other hand, are controlled centrally by brand managers,

and are frequently based on competitive dynamics. All these separate pricing

decisions usually create a wide price band.

3.4

Yet companies are seldom aware of this state of aƒfairs. Ask most managers

why their companies set prices at a given level, and they will tell you that this

is the highest price consumers are willing to pay. But if that is so, why do list

prices keep rising while a substantial portion of the increases go to finance

≠ EDLP (everyday low price) is a retail pricing strategy in which the retailer charges a constant,

relatively low everyday price with no temporary price discounts. Hi-lo retailers, by contrast,

charge higher prices on an everyday basis and run frequent promotions in which prices

temporarily fall below the EDLP level.

118

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1998 NUMBER 3

WHY YOUR PRICE BAND IS WIDER THAN IT SHOULD BE

trade and consumer promotion budgets? In any case, few companies can tell

how much product they sell at full price to end consumers.

Ask the same managers who actually makes their companies’ price decisions,

and the response is likely to be the “brand people” at HQ, who are specialists

with the necessary tools for the job. Both impressions are false. Roughly

12 percent of sales come under trade promotion budgets, more than half

of which (and growing) are controlled in the field. Frontline salespeople

therefore direct a good deal of the tactical pricing for any brand.

Yet few companies have taken the vital steps to hire and train the right

salespeople and to provide them with the data and analytical tools they need

to measure the profitability of their promotions. Even relatively simple

metrics like purchase cycles and pantry loading are rarely linked to tactical

promotional strategies. As with many other changes in the marketing mix,

variations in pricing are seldom based on an analysis of their impact in

specific consumer segments. Even leading packaged goods companies are

confused about the correct interpretation and use of price elasticity. As a

result, companies oƒten make major pricing moves that substantially reduce

their profitability.

Prices are set in an ad hoc way for several reasons. First, companies generally

use discounts to meet competition, an approach that their customers, retailers,

strongly encourage. Second, promotional spending is typically budgeted on a

highly unfocused “what we spent last year plus 5 percent” basis. Third,

customer (retailer) strategies oƒten drive pricing: EDLP accounts, for

example, may demand that manufacturers set an everyday price lower than

the list price plus average customer margin. For many manufacturers, this

not only forces down the top end of the price band but also reduces its

potential width.

Sensible pricing calls for a deep knowledge of consumer behavior and a welldefined process to translate this knowledge into local pricing decisions. An

understanding of consumers is the only basis for doing what companies claim

to do: price at the highest point consumers will pay. Although knowledge

about competitors, channels, and retailers is vital, it should supplement rather

than replace this understanding; everything else is secondary. In setting price

bands, the objective should be to increase volume from price-sensitive

consumers by lowering the price to them, and to increase profits from priceinsensitive segments by capturing the value inherent in the product oƒfering.

Determining the ideal price band

A wide array of consumer-related drivers can aƒfect pricing, among them the

dynamics of usage and purchase occasions, loyalty to product attributes, and

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1998 NUMBER 3

119

WHY YOUR PRICE BAND IS WIDER THAN IT SHOULD BE

local market preferences. Two consumer drivers are particularly important:

first, the extent to which consumption in a category can be expanded through

price/promotion policy; second, brand equity.

It is possible to raise sales volumes in expandable categories, such as salty

snacks, cookies, and soƒt drinks, by raising consumption among current or

new users through attractive prices or promotions. Pepsi, for example, believes

that as much as 50 percent of the incremental volume generated by promotions may come from increased category consumption. Wider price bands

are usually appropriate in expandable categories, since incremental volume

can increase total profits despite reducing profit per unit.

The second driver, brand equity, refers to a consumer’s relationship with a

product’s tangible or intangible benefits. Power brands – those with high

equity – command a price premium and also allow their owners great

flexibility over pricing.* Such brands as detergent Tide and snack food

Doritos capture consumer surpluses by oƒfering shallow price discounts

(narrow price bands) to encourage pantry loading by loyal consumers or to

attract switchers or formerly loyal consumers of competing brands. They

can also use periodic deep discounts (wider

price bands) to attract buyers who would not

Understanding consumer

normally buy products in the category.

drivers makes it possible

to determine the proper

width of a price band

Understanding these two drivers makes it

possible to determine the proper width of a

price band. If category consumption appears

to be highly expandable and a manufacturer has the strongest brand, for

example, it should adopt a very wide price band: that is, set the everyday

price high and promote heavily. This will capture the benefit of loyal consumers’ willingness to pay while simultaneously increasing volume among

occasional or new users through profitable promotions.

Suppose, however, that a brand in an expandable category lacks high brand

equity. In this case, narrower price bands, combining moderate everyday

prices with moderate levels of promotional activity, are appropriate. It is

unwise to charge high everyday prices for such a product, but profitable

promotions can still increase brand (and category) consumption.

Imagine that the expandability of a category is low but the equity of a brand

within it is high, as it is for leading brands of toilet paper and detergent, as

well as many luxury goods. The right policy is to deploy the narrowest price

bands and to use promotions sparingly. Such brands do not benefit from

promotions in the long run, because the sales thus generated are likely to be

≠ David C. Court, Anthony Freeling, Mark G. Leiter, and Andrew J. Parsons, “If Nike can ‘just

do it,’ why can’t we?,” The McKinsey Quarterly, 1997 Number 3, pp. 24–34.

120

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1998 NUMBER 3

WHY YOUR PRICE BAND IS WIDER THAN IT SHOULD BE

made at the expense of future sales of the brand or to come from switchers

who buy on a deal-by-deal basis. Reducing promotions of such brands (and

encouraging competitors to do likewise) will probably reduce the size of the

deal-by-deal switching pool.

Once the ideal width of a price band has been established, four issues must be

addressed before it can be implemented in the marketplace:

• What should the everyday price be?

• How wide should the price band be? In other words, exactly how far below

the everyday price should a company set the promotional price level?

• What mix of promotional levers is most eƒfective?

• How oƒten should a company promote?

Setting everyday prices

To determine the profit-maximizing everyday price for an SKU, a company

needs a good understanding of price elasticity, key threshold prices and price

diƒferentials, and company margins. Sophisticated econometric modeling

of sales and price data by such marketing information suppliers as Nielsen

and IRI can help companies estimate the price elasticity of their brands. In

some cases, it may be necessary to employ other methods, such as in-store

experiments and various forms of choice modeling (for instance, conjoint

or discrete choice).

Threshold price points – say, $1.99 – are levels above which consumer demand

falls sharply and below which consumer demand fails to rise in proportion.

They exist for key items in a category and for the brands competing in it.

Oƒten, threshold price points are specific to a market or region; in some cases,

they are specific to an account as well.

The price diƒferential is the point at which the diƒference between the price of

a brand and that of a key competitor becomes large enough to reduce the

brand’s sales velocity substantially. Detailed analysis of price diƒferentials

can be valuable: we found that one company aimed for a certain price

diƒferential against a key competitor nationally, but the key competitor and

the optimal price gap actually diƒfered from region to region. A national

analysis was not suƒficient to assess the appropriate diƒferential.

As a rule, companies undertake a systematic analysis for one major package

or size of a brand and then use judgment and conventional wisdom to

extrapolate the findings to other packages or sizes. But if small sizes appeal

chiefly to occasional users and large sizes to heavy loyal ones, prices should be

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1998 NUMBER 3

121

WHY YOUR PRICE BAND IS WIDER THAN IT SHOULD BE

proportionally higher on the large size to maximize the surplus, and lower

on the small size to bring in occasional users. In one documented case,

adopting this approach pushed margins up by 5 percentage points – an

extraordinary increase in profitability.

Setting the width of the price band

Once a company has identified appropriate everyday prices, it must set

the lower bound of the price band. Empirical studies suggest that price

reductions eventually cross a threshold beyond which further cuts fail to

attract more switchers and new users and add only slightly to incremental

volume (Exhibit 2). Although optimal promotional discounts are likely to be

Exhibit 2

Lo

ya

ls

Co

m

lo pe

ya ti

l s ti v

e

Sw

itc

he

rs

Finding the price reduction threshold

Example: Household product

Thousands of units

12.6

Everyday price

6.05

10% price cut with in-store display

0.5

6.05

35.0

7.7

20% price cut with feature advertisement

16.8

10.5

40.0

14.0

12.0

14.0

Source: A. C. Nielsen

Exhibit 3

Determining price bandwidth

Aggregate data

500

Feature

advertisement

and in-store

display

Price band

Sales index

400

In-store display only

300

Feature advertisement

only

200

Temporary

price

reduction only

100

0

10

20

30

40

brand specific and must be

determined empirically, an

analysis of 30 product categories across many US markets shows that consumer

responses flatten for price

discounts steeper than 30 to

35 percent (Exhibit 3). This

suggests a lower limit for

price bands.

Adjusting the price band

through diƒferent

promotional levers

Manufacturers should understand which promotions

appeal to which consumers.

Our experience suggests that in general, feature advertisements attract a

disproportionate number of brand loyalists, while in-store displays lure

switchers. We have also found that inserting coupons into flyers distributed in

stores targets price-sensitive consumers more eƒfectively than does cutting

prices at the shelf. Only about half of the shoppers who buy the promoted

Discount, percent

Source: A. C. Nielsen

122

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1998 NUMBER 3

WHY YOUR PRICE BAND IS WIDER THAN IT SHOULD BE

brand take advantage of these coupons; other consumers ignore them and

pay a higher price.

Although these findings cannot be generalized to all brands and categories,

manufacturers can use promotional levers in a fairly targeted way to attract

the price-sensitive segments that they seek. To do so, however, they must

undertake detailed analyses of the consumer data that is increasingly

available at market and account levels. Companies must be creative in

designing promotions, measuring their sales and profit impact on target

segments, and identifying those that will allow them to customize their prices

while generating profitable incremental volumes.

Determining the right frequency for promotions

Consumers’ responsiveness to the frequency of promotions varies by geography, category, and brand. Two key issues to consider are reference prices

and category dynamics. Reference prices formed by consumers help them

determine whether products give good value. Manufacturers should aim to

keep reference prices and the everyday prices consumers see when they shop

as high as possible, since evidence suggests that for most consumers, frequent

promotions can push the reference price of a product far below its everyday

price. By contrast, less frequent or random promotions make consumers feel

they are getting a bargain – a more desirable result.

Two kinds of category dynamics are important. The first is the category and

brand purchase cycle of the segment being targeted: if consumers purchase

a product in a given category once every two months on average, weekly

promotions are not likely to be productive. The second is the frequency with

which the brands in a category have been promoted in the past. Many categories are promoted excessively. If past practice has created certain expectations among consumers about promotions for a given category, it can be

hard to change them. It will be necessary to take a gradual approach, moving

steadily toward the optimal lower level of promotion.

Adjusting the price band

Although price bands should be based on a deep understanding of consumers, traditional concerns about competitors and channels cannot be

neglected. The study of consumer dynamics does implicitly take some of

these concerns into account, but it is worth keeping an eye on them directly

to fine-tune pricing strategy.

Competitors

Some companies react to the pricing and promotional moves of all competing companies in the same way, failing to realize that all competitors

are not equal. Consumer analysis suggested that one company’s brand

stole share from a key competitor whenever it was promoted. Yet when the

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1998 NUMBER 3

123

WHY YOUR PRICE BAND IS WIDER THAN IT SHOULD BE

competitor promoted its own brand, the first company’s sales were not

aƒfected. Asymmetrical competition of this kind is common, particularly

when consumers feel that brands vary in quality and a category is divided

into distinct price tiers. Consumers trade up relatively easily to better-quality,

more expensive brands, but resist trading down to lower-quality brands even

if they represent a bargain.

In adjusting price bands in response to competitors, there are several key

issues to consider:

• If a company wants to create a wide price band for its brand, how should

it respond if competitors do not follow its lead, or even take steps to narrow

their own price bands?

• If a company wants to narrow the price band for its brand, how should it

respond to competitors who buy market share by means of aggressive

unprofitable promotions?

• How does a company go about influencing its industry if it wants to lower

the level of promotional activity in an unexpandable category?

Companies spend large amounts of their money on trade and consumer

promotions that discount prices to competitive levels, thus widening the price

bands of their brands. They should think twice before doing so. The desire to

meet competition is rarely a sound basis for pricing decisions; indeed, it is

unlikely to raise the profits of any of the competitors. Why? Because retailers

hardly ever advertise or discount competing products at the same time; the

“meet the competition” philosophy means that one company’s product will be

discounted this week, another company’s next week. Since discounting is

oƒten unprofitable, this approach tends to depress a company’s profits twice:

once when its competitor discounts, and again when it takes its turn.

One company battled it out in this kind of promotional war with its only

major competitor in a certain region. Both players eroded shareholder

value by oƒfering attractive prices to retailers almost continuously. The

retailers, fierce competitors themselves, used this category to build traƒfic

for their stores. The two companies were trapped in a vicious cycle of

price discounting.

A thorough analysis of everyday price and promotional elasticity and consumer behavior persuaded the company to implement consumer-driven

pricing strategies. It narrowed its price bands, used targeted promotions

to reach specific segments in some channels, and increased margins by

4 percent. The competitor followed suit by narrowing its price bands –

presumably with positive results as well.

124

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1998 NUMBER 3

WHY YOUR PRICE BAND IS WIDER THAN IT SHOULD BE

Channels

Consumers purchase packaged goods from many retail channels, each with

its own distinct value proposition; even retailers within a given channel

have a variety of formats. Grocery stores, which oƒfer convenience and a wide

assortment of products, oƒten charge relatively high prices for items that are

not in the grocery line, such as diapers and toothpaste. By contrast, warehouse

clubs targeting price-sensitive consumers oƒfer the lowest prices, but have

only a limited assortment of package sizes, primarily large. Many brands sell

in multiple channels, with multiple positionings.

For some products, consumer price bands should be adjusted channel by

channel. Consider the pricing of beer. Category and brand consumption can

be expanded much more readily in supermarkets than in bars. This suggests

that a wide price band is more appropriate for supermarkets. (Happy hour

discounters beware!)

More generally, companies must answer three key questions:

• Is a given strategy suƒficiently flexible for all channels, and in particular

for the major accounts within them?

• Do consumers use a product to judge the

overall value proposition of a channel or

retailer? What role does the category play in

the retailer or channel value proposition?

Pricing strategies must be

flexible enough to accommodate

diƒferent retailers without

jeopardizing a brand’s overall

price positioning

• How can a pricing and promotion strategy

be tailored to work both for manufacturer and for retailers?

Bear in mind that retailers as well as manufacturers have price positions they

wish to project to consumers. If a manufacturer adopts a pricing strategy

that is based on heavy promotion, such as hi-lo, it can easily fail if the primary

channels for selling the product are oriented to EDLP. Pricing strategies must

be flexible enough to accommodate diƒferent retailers without jeopardizing a

brand’s overall price positioning. Companies should ask themselves what

price bands are appropriate for retailers whose maximum diƒferential between

high and low prices is as low as 20 percent. This approach to the overall

design of pricing programs may seem merely common sense, but in our

experience, it is seldom pursued.

Executing the price band in the field

Even well-designed pricing programs oƒten fail because of inconsistent or

weak execution. Since final prices reflect many local decisions, field capabilities and incentives must be aligned with a company’s overall pricing structure.

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1998 NUMBER 3

125

WHY YOUR PRICE BAND IS WIDER THAN IT SHOULD BE

Poor execution in the field has many causes. Some companies buy whatever

information they need to manage their top accounts and brands, but fail to

put all of it in the hands of the people who could really use it to improve

brand movement, volumes, and profits. Few companies go so far as to

measure their returns on promotions. If they did, many would find they are

negative. One manufacturer discovered that more than 10 percent of its

promotional spending on a particular food category was wasted, since

increases in consumption peaked at a discount level of 20 percent, yet many

of its promotions cut prices by 50 percent

or more. By adjusting price targets, this

Few companies go so far as

company gained almost an extra percentage

to measure their returns on

point in profits.

promotions. If they did, many

would find they are negative

The same account-level data that can be used

to determine whether a manufacturer and an

account have made a profit on individual trade deals can be mined even more

deeply to isolate the impact of price levels and price bands. But in order to

glean such insights, a company must make both its data and the right tools

available to its frontline salespeople, since input from them can help it build

a robust picture of what is happening in the real world. Discipline is needed

if a company is to create a suitable base of knowledge and synthesize it across

regions and channels.

Packaged goods manufacturers can boost their bottom line by taking several

steps to increase the eƒfectiveness of their salesforces:

• Recognize the critical role frontline salespeople should play in the pricing

process.

• Equip the salesforce to handle this role by giving it account-level pricing

and profitability data, easy-to-use tools, and support functions specific to

account-level pricing. (This might include data gathering, financial analysis,

or local marketing expertise.)

• Maintain pricing discipline by continually measuring the impact of price

levels on the eƒfectiveness of promotions, and intensively educating the

salesforce on best practices by account and by channel.

• Use a bonus program to reward salespeople for devising price levels that

build brand equity and increase the profitability of brands and accounts.

Easy though these steps may sound, most packaged goods companies have

diƒficulty taking them, largely because they entail an enormous change in

mindset. Field sales organizations must become more analytical and more

focused on profits. The marketing function must be willing to give the

126

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1998 NUMBER 3

WHY YOUR PRICE BAND IS WIDER THAN IT SHOULD BE

salesforce more flexibility to set pricing than it has previously enjoyed.

Finally, marketing and sales must agree on the level of sales they want to

achieve, and why.

Shiƒting the orientation of pricing strategies for packaged goods from the

current fixation with competition and channels to an approach that takes

fuller account of consumer behavior oƒfers promising opportunities to

improve profits. But a new mindset at headquarters, new techniques for

measurement and analysis, and new capabilities are needed before a company

can recognize and capture the profit potential of innovative pricing. Once

these are in place, it can turn to the diƒficult challenge of training frontline

salespeople, providing them with adequate decision support tools, and

adjusting their incentives. What lies ahead is no easy task. But a margin

improvement of 2 to 5 percent is quite an incentive.

THE McKINSEY QUARTERLY 1998 NUMBER 3

127