Civil High Court Guide - Bowman Gilfillan Inc.

advertisement

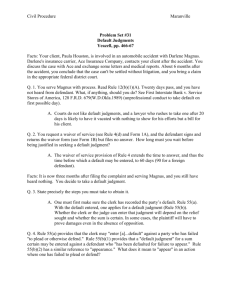

BASIC GUIDE TO CIVIL HIGH COURT L I T I G AT I O N You think outcome. We think process. Our horizons are as broad as your business vision. Overview The Bowman Gilfillan Africa Group Bowman Gilfillan Africa Group is one of Africa’s premier corporate law firms, employing over 400 specialised lawyers. The Group provides domestic and cross-border legal services to the highest international standards across Africa, through its offices in South Africa, Botswana, Kenya, Madagascar, Tanzania and Uganda. Differences in law, regulation and business culture can significantly increase the risk and complexity of doing business in Africa. Our aim is to assist our clients in achieving their objectives as smoothly and efficiently as possible while minimising the legal and regulatory risks. While reliable technical legal advice is always very important, the ability to deliver that advice in a coherent, relevant way combined with transaction management, structuring, negotiating and drafting skills is essential to the supply of high quality legal services. The Group has offices in Antananarivo, Cape Town, Dar es Salaam, Gaborone, Johannesburg, Kampala and Nairobi. Our office in Madagascar, has francophone African coverage in Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo Republic, Gabon, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal and Togo. We have a best friends relationship with leading law firm Udo Udoma & Bela-Osagie, in Nigeria, which has offices in Lagos, Abuja and Port Harcourt. We also have strong relationships and work closely with law firms across the rest of Africa which enables us to provide or source the advice clients require in any African country, whether on a single country or multi-jurisdictional basis. We act for corporations, financial institutions, state owned enterprises and governments providing clear, relevant and timely legal advice to assist clients achieve their objectives and manage their legal risks. Geographical and sector specific teams are utilized to provide clients with the highest standards of service. In the cross-border arena the Group has extensive experience in the resources, energy, infrastructure, financial institutions and consumer goods sectors. This booklet describes, in basic terms, the procedures for pursuing matters in the High Court. It is neither intended to be a detailed or authoritative exposition of those procedures, nor to deal with practice in the Magistrates Courts. Any questions that readers may have arising out of the contents of this guide may be raised with any of the members of Bowman Gilfillan’s dispute resolution department. A list of directors and senior associates is located at www.bowman.co.za. Contents Attorneys and Advocates 02 The Letter of Demand 02 Jurisdiction 03 Action or Motion Proceedings 03 The Action Procedure (Trial Procedure) 04 Trial Preparation 10 Execution of Judgments 17 Execution 18 Garnishee Orders 19 Enforcement Of Foreign Judgments 20 The Application Procedure 21 Recovery Of Costs 22 Bowman Gilfillan Africa Group’s South African, Kenyan and Ugandan offices are representatives of Lex Mundi, a global association with more than 160 independent law firms in all the major centres across the globe. This association gives access to firms which have been identified as the best in each jurisdiction represented. 01 Attorneys and Advocates The Letter of Demand Jurisdiction Like England, South Africa has a split bar system, consisting of attorneys and advocates. A letter of demand is generally the first step in the legal process. While a letter of demand is required in some instances, it does not need to be sent in all circumstances. It is, however, usual practice that a letter of demand will be sent before instituting legal proceedings. Jurisdiction refers to the authority or competence of a particular court to hear a matter and to grant relief in respect of that matter. The advocates’ profession is a referral profession, which means that advocates cannot accept briefs directly from clients. The attorney is approached by the client and it is the attorney who takes instructions from the client and briefs the advocate. An advocate (also called counsel) will generally provide strategic advice, settle pleadings and represent the client in court or in arbitration proceedings. Advocates are either senior or junior counsel. Senior counsel, or silks, are advocates who have many years of experience and who have had the status of Senior Counsel conferred on them by the President. They will be briefed generally for complex matters where they have specialised skills and expertise. Junior counsel are less experienced advocates and will charge substantially less than senior counsel. Where appropriate, junior counsel will be briefed alone but, where the matter is complex or the claim is substantial, it is often necessary to brief both a senior counsel and a junior counsel. Attorneys who have obtained right of appearance may appear in the High Court but in complex and substantial matters the tradition of utilising counsel remains prevalent. When counsel is briefed, the role of the attorney is to instruct the advocate on behalf of the client, and advocates may not consult with clients unless the instructing attorney is present. A letter of demand is, as its title suggests, a letter addressed to the other party demanding, for example, fulfilment of an outstanding obligation or payment of a sum of money. Generally a letter of demand will set out the cause of action on which the demand is based, and will give the other party time to comply with the demand. If the demand is met then no further steps will be taken. It is first necessary to determine whether the High Court or a lower court (i.e. Magistrate’s Court or Small Claims Court) has jurisdiction to hear the matter. Determining whether to proceed in a lower court or in the High Court will depend on the type of claim and the value of the claim. The Small Claims Court is competent to hear matters where the value claimed is below R12 000, and only individuals may bring claims in this court. The Magistrate’s Court is constrained to matters where the value claimed is R300 000 or less. The parties can, however, agree to the jurisdiction of the Magistrates Court in claims exceeding R300 000. There are certain matters which may only be heard by the High Court, regardless of the quantum of the claim. Once it has been established that the High Court has jurisdiction, it must be decided which seat of the High Court is competent to hear the case. As a general rule, a court will exercise jurisdiction on the basis that the defendant is resident or domiciled in the area of the court or if the cause of action arose in that area. Action or Motion Proceedings Once a decision has been made to embark on litigation in the High Court it is necessary to determine whether to proceed by way of trial (action) or motion (application) proceedings. In action proceedings, the person bringing the action is called the plaintiff, and the person defending the action is called the defendant. In application proceedings, the person bringing the application is called the applicant, and the person defending the application is called the respondent. In determining whether to proceed by way of action or application, the question to be asked is whether a material dispute of fact is anticipated. If a dispute of fact is anticipated then generally it is best to proceed by way of action where witnesses may be called to give oral evidence at a trial. If no such dispute of fact is anticipated then application proceedings are probably appropriate. In an application, the matter will be determined with reference only to the papers and, as a general rule, no oral evidence is permitted. The disadvantage with motion proceedings is that the evidence is set out in affidavits and cannot be tested by cross-examination. Consequently, it is difficult for a court to decide between conflicting versions. The advantage of motion proceedings is that they are generally speedier and less expensive than actions. If the court is faced with an application in which it is evident that there is a material dispute of facts between the parties then the court will refer the matter to trial. The different procedures are set out more fully below. 02 03 The Action Procedure (Trial Procedure) The Summons The issue and service of a summons commences the trial action. The purpose of a summons is to bring the plaintiff’s claim to the attention of the defendant by informing the defendant of the nature of the plaintiff’s cause of action and the claim made. The summons generally informs the defendant that it has 10 business days within which to deliver a notice of intention to defend the action and that failure to give notice within the prescribed time will allow the plaintiff to apply for default judgment against it. There are two types of High Court summonses; a simple (ordinary) summons and a combined summons. The nature and complexity of the plaintiff’s claim will determine what type of summons is used. A simple summons is used when the cause of action is based on a debt or liquidated demand. A combined summons is used when the plaintiff’s claim is not founded on a debt or liquidated demand. In addition, in a simple summons, there will be no detailed particulars of the claim attached, as is the case in a combined summons. Rather, a brief description of the plaintiff’s cause of action will be given (such as money lent and advanced), as well as the relief claimed by the plaintiff. Once the defendant delivers a notice of intention to defend after receipt of a simple summons, the plaintiff will deliver a declaration, which sets out the cause of action in more detail. This is similar to particulars of claim attached to a combined summons. The particulars of claim, which is attached to a combined summons, outlines the nature of a plaintiff’s claim and the relief sought against a defendant. The particulars of claim will set out a description of the parties to the action, the background to the dispute, and will ensure that the claim and all the facts upon which the claim is based are fully outlined. The particulars of claim must contain sufficient detail to enable to the defendant to defend the allegations made against him and must include a copy of any written agreement that is relied upon. 04 A simple summons may be signed by the plaintiff or the plaintiff’s attorney. A combined summons must be signed by the plaintiff or by its attorney and an advocate or an attorney with right of appearance in the High Court. Once signed, the summons is then issued by the registrar of the High Court concerned. Once the summons has been issued by the Court, the summons is sent to the appropriate sheriff with instructions to serve the summons on the defendant at his residence or place of business. Once the sheriff has served the summons, he will complete a return of service to indicate that service was successful. A defendant is only deemed to have received the summons when the summons has been properly served by the sheriff. Provisional Sentence Summons A provisional sentence summons is an extraordinary procedure in terms of which a plaintiff in possession of a document showing an indebtedness for a liquidated sum of money, for example, a cheque, may obtain provisional judgment for the amount payable on the face the document prior to the trial date. The rationale behind this is that the court will grant a provisional judgment in favour of the plaintiff on the basis that in issuing the document in question the defendant has acknowledged its indebtedness to the plaintiff for the amount stated in the document. The court must be provisionally satisfied that the plaintiff will succeed in the principal case. The advantage of this procedure is that it allows a plaintiff to promptly recover a money debt from the defendant. The purpose is to bring proceedings to a speedy end especially when the defendant does not have a defence to the plaintiff’s liquid claim. If the defendant disputes the allegations, the onus is on the plaintiff to prove that they are true. The judgment obtained by the plaintiff at the early stage is provisional and cannot prevent the defendant from proceeding to the principal case. In a recent Constitutional Court judgment the constitutionality of the provisional sentence procedure was considered. The Constitutional Court held that the courts should have a discretion to refuse provisional sentence in certain limited circumstances; namely, where there defendant is unable to pay the judgment debt, there is an even balance of success between the parties on the papers, and there is a reasonable prospect that oral evidence will enable the defendant to successfully prove his case. Notice of Intention to Defend After service of summons by sheriff, the defendant is generally given 10 business days in which to deliver a notice indicating his intention to defend the action. The notice must set out an address for the service of documents on the defendant. This will generally be the address of the defendant’s attorney, which must be within 15 kms of the High Court concerned. Where the plaintiff’s attorney is further than 15 km from the Court, the attorney will need to appoint a correspondent firm of attorneys within 15 kms of the Court, who will act as a post box for the receipt of court documents. An application for summary judgment must be served within 15 days of the delivery of a notice of intention to defend. In most instances the plaintiff will be granted summary judgment where the defendant has no bona fide defence and has entered an appearance to defend solely for the purposes of delaying the action. Summary judgment can only be sought where the defendant has delivered a notice of intention to defend, the plaintiff’s case is based on a liquid document or a liquidated amount of money, the delivery of specified movable property, or ejectment from property, and the plaintiff believes that the defendant does not have a bona fide defence and is merely trying to delay judgment. There are two ways in which a defendant may defeat an application for summary judgment. He may give security to the value of the claim to the plaintiff or satisfy the court that he has a bona fide defence to the claim. Default Judgment A plaintiff may apply for default judgment where a defendant has failed to serve a notice of intention to defend within the prescribed time or where the defendant has failed to deliver its plea after receiving a notice of bar from the plaintiff. Where the prescribed time lapses, the plaintiff is entitled, without further notice to the defendant, to apply for final judgment against the defendant. Where default judgment is granted, the plaintiff is able to demand compliance with the judgment. Where the defendant was not aware of the service of the summons, it is possible for the defendant, on learning of the judgment against him, to apply for a rescission of judgment. This application is supported by an affidavit which must provide a satisfactory explanation for the defendant’s failure to give notice of intention to defend and explaining the nature of the defence that will be raised. Summary Judgment Summary judgment can be sought in certain circumstances when an action is defended. It is a remedy which is pursued by a plaintiff seeking speedy judgment at an early stage without the delay and expense of a trial. Where security is provided, the court has no discretion and must grant leave to defend. Where the defendant maintains that he has a bona fide defence, the defence must be explained in an affidavit. As summary judgment is final courts are often reluctant to shut the doors to the defendant. Accordingly a court has a discretion whether or not to allow the defendant leave to defend the action if it has served an affidavit that appears to set out a defence. Exceptions Before the defendant delivers his plea (statement of defence) he may raise defences that do not go into the merits of the case, but rather to technical legal issues. This may be done by special plea or exception. An exception is an objection to a material defect in the opposing party’s pleadings. Where a defendant wishes to take exception to a declaration or particulars of claim, then he must do so within 20 days after the service of a declaration or 20 days from the date on which the defendant files a notice of intention to defend. Where the plaintiff wishes to take exception to the defendant’s plea, then it must do so within 15 days after the service of the defendant’s plea. 05 An exception may be raised where, for example; the pleading is vague and embarrassing (unintelligible, contradictory or lacking in particularity), or it lacks the statements necessary to sustain a cause of action or a defence (it does not contain the material allegations required for the cause of action or defence to be relied upon, or the claim relied on is bad in law). Special Plea A special plea is a separate, special defence which either destroys the cause of action or postpones its operation. A few examples of defences which may be raised as special pleas are as follows: that a party with an interest in the matter has not been cited as a plaintiff or defendant, that the matter has been bought in the incorrect court, that the plaintiff is not competent to bring the matter to court, that the time period within which to bring the action has prescribed, that the same matter is already before a competent court, or, where there is a contractual dispute, that there is an arbitration clause in the contract and the matter must be referred to arbitration and decided by an arbitrator. Plea A plea (statement of defence) is the defendant’s response to the plaintiff’s summons and must be delivered within 20 days after the defendant has delivered its notice of intention to defend. Failure to file a plea in the prescribed time period entitles the plaintiff to deliver a notice of bar calling on the defendant to deliver the plea within 5 days. Should the defendant fail to do so then the defendant is barred from delivering his plea and the plaintiff may then apply for default judgment as the defendant has failed to defend the claim. In practice however, before barring the defendant, the plaintiff’s attorneys will as a courtesy send a letter to the opposing attorneys demanding that the outstanding plea be delivered within a certain period of days. The plea must set out the defence upon which the defendant relies and must contain a paragraph-byparagraph reply to each of the allegations made by the plaintiff in its particulars of claim. The defendant will 06 admit, deny or confess and avoid each of these specific allegations. Where a defendant fails to deal with a specific allegation, then the allegation is deemed to be admitted. The Counterclaim and the Plea to the Counterclaim A counterclaim or claim in reconvention is the defendant’s separate cause of action against the plaintiff. If a defendant wishes to bring a counterclaim, he is obliged to do so when filing his plea. The plaintiff does not need to deliver a notice of intention to defend the counterclaim, but the plaintiff must then deliver a plea to the counterclaim, in which the plaintiff must set out its defence to the counterclaim. The plea to the counterclaim must be delivered at the same time as a replication, if one is to be delivered. The Replication A replication is the plaintiff’s response to the defendant’s plea and is necessary only when the plaintiff wishes to place new facts before the court or clarify issues raised in the counterclaim. Interlocutory Procedures Interlocutory procedures are concerned with resolving side-line issues prior to the trial taking place. They are always brought by application and are dealt with separately from the main trial. Trial Preparation What happens after pleadings are closed? Once all the pleadings have been filed, pleadings are then deemed to be closed. Between this stage and the trial a number of important procedures take place. The most important of these procedures is discovery. Applying for a Court Date Once pleadings have closed the next step is to apply for a court date from the registrar of the appropriate court. The plaintiff usually requests the trial date but it may also be requested by the defendant if the plaintiff fails to do so within six weeks after the close of pleadings. Discovery Discovery is one of the most important steps in pretrial preparation and is based on the principle that a party is entitled to be notified prior to the hearing of the matter of all the documentary evidence, including tape recordings and e-mails, which the opposing party possesses which are relevant to the matter. Discovery is the procedure in terms of which the parties disclose to each other all relevant documents and tape recordings that they or their agents have in their possession or under their control. Discovery is made by way of affidavit to which a list is annexed listing all the documents in the discovering party’s possession. Generally, a party will not be allowed to use any documents that he has failed to disclose in response to a request for discovery. There are however, certain exceptions to need to disclose relevant documents. These include witness statements taken for the purposes of the trial, communications between attorney and client, communications between attorney and advocate and pleadings, notices and affidavits in the action. There are certain other documents which are considered to be privileged, and which likewise need not be discovered. These include, amongst others, communication made in a bona fide attempt to negotiate settlement and documents which fall within professional legal privilege. Each party may call on the other party to make discovery. This is done in the form of a notice requesting the delivery of the discovery affidavit within 20 days of receipt of the notice. Pre-trial Conference Within a perscribed period before the trial date the attorneys and counsel representing the parties must attend a pre-trial conference. The primary purpose of this conference is to facilitate a discussion between the parties to find ways of expediting the process by limiting the issues between the parties for the purpose of trial. It also provides the parties with an opportunity to settle the matter before going to trial. A formal minute of the pre-trial conference is prepared and is required to be handed to the presiding judge prior to the trial. Security for Costs Where there is a reasonable apprehension that the plaintiff or applicant will be unable to pay the costs of the matter if an award is granted against them, then the defendant may call for security for costs. Although the court has a discretion, it will probably order security for costs when: the plaintiff is neither resident nor domiciled within and does not own immovable property in South Africa; the plaintiff institutes proceedings which the court considers vexatious; or the plaintiff who instituted the proceedings is litigating in a nominal capacity and is found by the court to be a ‘man of straw’ behind whom the plaintiff is sheltering. In terms of section 13 of the Companies Act 61 of 1973, courts had a discretion to order a company that instituted legal proceedings to furnish security for costs if there was a belief that the company would not be able 07 to pay the costs of the other party. Section 13 has now been repealed by the Companies Act 71 of 2008 and there is no equivalent provision. Recent case law has held that, despite the repeal of section 13, the courts still have an inherent power to regulate their own process. Accordingly, each case will be decided on its own set of facts. If there appears to be a necessity for security for costs then the courts may grant security for costs against a company. A notice calling for security for costs needs to be delivered as soon as possible after proceedings commence. This notice must set out the grounds for requesting security for costs. On receipt of this notice, the plaintiff may either provide the requested security, dispute the amount of security requested, or dispute liability to give such security. In the latter case the party who requests security can apply to the court for an order that security be furnished. If only the amount of security is in issue, the registrar will fix the amount. The main proceedings can, by order of the court, be suspended until any order granted is complied with. The amount to be provided as security is generally determined by an official in the office of the registrar known as a taxing master. A plaintiff or applicant may oppose the amount requested before the registrar. A plaintiff’s failure to comply with an order for security for costs may lead to a dismissal of the application or action. Settlement A dispute between parties may be settled at any time prior to judgment. In practice, one party (often the defendant) will approach the other party with a settlement proposal setting out the terms on which that party is prepared to settle the matter. The other party can then accept the proposal, reject the proposal or make a counter-proposal. If the claim is settled then the parties will generally record the terms of the settlement in a written settlement agreement. 08 A settlement proposal can either be made on the record or off the record. Where a settlement proposal is made off the record and the proposal is not accepted, then the proposal may not be used or referred to in court or arbitration proceedings. This is because the proposal has been made with a bona fide intention to settle the matter and the party making the proposal should not be prejudiced during the trial or arbitration if the proposal is not accepted. Sometimes a party may wish to make an on the record settlement proposal. In these circumstances, if the proposal is not accepted, then either party may refer to the proposal during the proceedings. The advantage of making an on the record settlement proposal is that it illustrates to the judge that the party making the offer is bona fide and has made every attempt to settle its dispute with the other party outside of the court or arbitration. A further settlement option available to a defendant is an offer to settle in terms of Rule 34 of the rules of the High Court. The rule provides that, in an action where a sum of money is claimed, the defendant may at any time, unconditionally or without prejudice, make a written offer to settle the plaintiff’s claim, which must be signed by the defendant himself or his attorney, who must be authorised in writing to do so. The offer will only be brought to the attention of the court after judgment is granted and if it becomes relevant regarding costs. Appeals and Review and Procedure Once judgment is delivered, a litigant that is dissatisfied with the judgment granted may, in certain circumstances, apply to have the judgment set aside by instituting either appeal or review proceedings. Appeals Review A decision of a court may be taken on review where the procedural correctness or fairness is questioned. It is the process in terms of which the proceedings of a lower court are bought before a higher court as a result of certain irregularities. As it is unlikely that the irregularity will be apparent from the record, in review proceedings external evidence will be required to prove the irregularity. Where a dissatisfied litigant is of the view that the judgment ought to be set aside because the court reached the wrong conclusion on the facts or law, the appropriate remedy is an appeal. Since an appeal involves a re-evaluation of the court’s decision, it will be based solely on the record of the proceedings. The proceedings of a lower court may be bought under review on the basis of: Appeal proceedings are instituted by lodging an application for leave to appeal. Leave to appeal is not granted automatically and the party bringing the application must first apply for leave to appeal to the court that handed down the decision. Leave to appeal must be sought within 15 court days after the date of delivery of the judgment or order in question. The application for leave to appeal will then be set down and heard by the same judge who presided over the proceedings in question. gross irregularity in the proceedings; and / or absence of jurisdiction on the part of the court; or interest in the cause, bias, malice or corruption on the part of the judicial officer; or the admission of inadmissible or incompetent evidence or the rejection of admissible or competent evidence. Review proceedings are brought by way of an application. A notice of motion and founding affidavit must be delivered which sets out the grounds, facts and circumstances upon which the review is alleged. Where leave to appeal is granted it will either be to the Supreme Court of Appeal (“SCA”) or to a full bench (usually three judges) of the High Court concerned. A further appeal may lie from a full bench to the SCA and from the SCA to the Constitutional Court, where there are constitutional issues which arise from the case. As a general rule, leave to appeal will be granted where there is a reasonable prospect of another court coming to a different decision. 09 The Trial Expert Witness Execution of Judgments Execution The focus of any action is the trial itself. The trial is the hearing by the court of evidence relevant to the dispute. A single judge will be allocated to hear the matter. Generally, the party making the claim bears the onus of proving its claim. As such, the plaintiff usually starts with its evidence first. Any claim must be proved on a balance of probabilities. An expert witness is a person who, either by way of qualification or experience or both, has specific knowledge in a particular area which is outside the knowledge or experience of the court. An expert witness will be called to express an opinion on the issues falling within his field of expertise. Once judgment is obtained in favour of a party (the judgment creditor), the party against whom judgment is granted (the judgment debtor) will either willingly comply with the judgment or be unwilling or unable to do so, for whatever reason. Where a party has been ordered to pay a sum of money, and he fails to do so, then the other party will be entitled to execute against his property. Counsel for the plaintiff will usually give an opening address to the judge. This is intended to provide the judge with an overview of the case. Oral evidence is presented by witnesses for each of the parties. These witnesses may be cross-examined by the opposing side and thereafter re-examined by the counsel who led the witness. Unless there has been agreement at a pre-trial conference to the contrary, a document must be proved by a witness who can testify to its origin and content. Judgment is generally reserved and handed down once the judge has had an opportunity to consider the matter. In less complex matters judgment may be handed down immediately after completion of oral argument. Prior notification must be given to the other party that expert evidence will be relied upon in order to allow the other side time to study the evidence and to properly challenge the substance of the expert’s report through an informed cross-examination. Prior notification is given to the opposing party in the form of a written notice which must be delivered at least 15 days before trial. This notice must give the name and occupation of the expert. At least 10 days before the trial, a summary of the expert’s opinion must be delivered to the other side. This must set out the opinion of the expert and the facts on which the opinion is based. Subpoenas Generally witnesses will attend trial to give evidence voluntarily. However, there may be times when a witness will be unwilling to co-operate and appear in court. In this instance, a subpoena may be issued by the registrar of the court, at the request of a party, and served on the witness by the sheriff. A subpoena is a document which compels the witness to appear at court. It is a criminal offence to disobey a subpoena. The subpoena informs the witness when and where to appear and may also require the witness to bring to court certain documents relevant to the matter. There are two forms of judgment, namely where the court orders the judgment debtor to perform some act, or where the court orders the judgment debtor to pay a sum of money. The remedies to enforce compliance with the court order differ in these two situations. Where a judgment debtor has been ordered to perform some act, and he fails to do so, the judgment creditor can apply to the court for an order declaring the judgment debtor in contempt of court and the judgment debtor may in those circumstances be committed to jail. In some cases, the court may order a third party, such as the sheriff, to perform the act required of the judgment debtor on its behalf, such as to sign documents to transfer property. Execution is the process in terms of which the judgment debtor’s property is attached by the sheriff and sold by public auction in order to raise funds to satisfy the judgment. Property which may be attached can be movable, immovable or incorporeal (i.e., share certificates or rights of action). However, execution will take place first against the movables and thereafter against any immovable property. Where an appeal is pending this suspends the execution of the judgment until finalisation of the matter. If the judgment debtor does not have sufficient executable property, then another means of collecting the money owed will need to be relied on. Since in this instance the judgment debtor is technically insolvent, the judgment creditor may wish to apply for the sequestration of the judgment debtor’s estate (where the debtor is an individual), or apply for the winding-up of the judgment debtor (where the debtor is a company). In execution of a judgment, the following occurs: A writ of execution is issued by the registrar of the court. This is a document ordering the sheriff to attach the necessary property of the judgment debtor. The sheriff will then serve the writ on the judgment debtor at his home or place of business. The sheriff will then request satisfaction of the debt. Sometimes the judgment debtor will at this point pay the amount owed as well as the costs incurred in obtaining the writ. If this happens then the attachment of his property is no longer necessary. If the writ is not satisfied, the sheriff will ask the judgment debtor to point out movable property to be attached. The sheriff should attach sufficient property to satisfy the judgment and costs. 10 11 The sheriff will then prepare an inventory listing the items which have been attached. This will then be given to the attorney who may, at that stage or thereafter, instruct the sheriff to take the items listed in the inventory into his custody and sell them. The sheriff will then sell the judgment debtor’s property by public auction until an amount has been raised that will satisfy the judgment and costs. This is done after due advertisement in suitable newspapers. Garnishee Orders A garnishee order is another means by which the judgment creditor may enforce a judgment. A garnishee order allows a judgment creditor to recover a judgment debt by attaching a money debt owed to the judgment debtor by a third party (the garnishee). Enforcement of Foreign Judgments As a general rule, the judgment granted by a court in a foreign country will have no direct operation outside that country. However, there are circumstances under which a foreign judgment may be recognised by a court in South Africa and where a judgment given by a South African court may be enforced in another jurisdiction. These circumstances will exist on the basis of either a treaty between the countries concerned, a piece of legislation, or on the basis of the common law of the state in which enforcement of the judgment is sought. In determining whether a South African judgment can be enforced in a foreign country, the laws of that country will need to be examined. Generally a judgment creditor will have to apply to the relevant court in the country to apply for an order recognising the judgment. A foreign country will be approached generally on the basis that some sort of comity exists between the two countries. Once a judgment is granted by a South African court to enforce a foreign judgment it has the same force and effect as any other judgment and is enforced in the same way. The Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards Act provides that a foreign arbitral award may be made an order of court in South Africa and thereafter enforced in the same manner as a local judgment. South Africa is a signatory to the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards, otherwise known as the New York Convention, which is widely considered to be the foundational instrument for international arbitration. It requires the domestic courts of state parties (i) to give effect to private agreements to arbitrate; and (ii) to recognize and enforce arbitration awards made in other state parties to the New York Convention. In determining whether a foreign judgment can be enforced in South Africa, the general rule is that in terms of comity, a foreign judgment can be relied upon as a cause of action. The foreign judgment creditor would issue a provisional sentence summons in South Africa, and the court may then grant provisional sentence in order to bring about its recognition. This will only be done if the court is satisfied of the existence of certain factors, including whether the recognition of the judgment would infringe on public policy. According to the Protection of Businesses Act, certain foreign orders, judgments, interrogatories or arbitration awards will not be enforceable unless the Minister of Trade and Industry has consented. These orders are widely defined as those which have been handed down in connection with any mining activity, any type of production, possession of any tangible property and almost any other act or transaction in, outside, into or from South Africa. The Minister’s consent, in practice, is rarely withheld. 12 13 The Application Procedure Calculation of Time Periods Also known as motion proceedings, the application procedure is based on the exchange of affidavits. Unlike the trial action, the usual rule is that no witnesses appear before the court to give evidence. The party bringing the application is known as the applicant, and the party opposing the application is the respondent. To commence proceedings, the applicant will issue a notice of motion, which sets out the applicant’s claim and the relief sought. An affidavit which supports the notice of motion is attached and is known as the founding affidavit. Supporting documents are attached to the affidavit. The notice of motion advises the respondent that if it wishes to oppose the application, it must give notice of its intention to do so within 5 days after it receives the applicant’s notice of motion and founding affidavit. After the respondent’s notice of intention to oppose has been delivered, the respondent then has 15 days to deliver an answering affidavit in which the allegations made by the applicant in its founding affidavit will be answered. The applicant may then, within 10 days, deliver a replying affidavit if it wishes to respond to any allegations made by the respondent in its answering affidavit. The applicant may then apply to the registrar for a date for the hearing. All facts should be included in the affidavits as it is not possible to place further evidence before the court at the hearing without leave of the court. In addition, all documents relevant to prove or disprove a party’s case must be attached to the affidavits. Since all evidence is placed before the court in affidavits a number of procedures that take place in action proceedings are not applicable in application proceedings. The hearing before the court is generally limited to oral argument by the counsel for the parties. However, the court may in certain circumstances refer certain issues or, in special circumstances, the entire matter, to oral evidence. As in trial proceedings, judgment is likely to be reserved and handed down at a later date after the judge has had an opportunity to consider the case. In less complicated matters judgment may be handed down immediately after oral argument. 14 Time periods for the delivery of documents are calculated by using “court days”, which exclude weekends and public holidays. The period 15 December to 15 January in every year is regarded as of period of dies non, literally meaning “no days” and these days are not included in the time period allowed for delivering an appearance to defend or a plea. Recovery Of Costs At the end of the trial or application, the court will hand down judgment and will make an order as to who must pay the costs of the trial or application. This is at the court’s discretion. Costs will generally be awarded in favour of the successful party. Although the purpose of such an order is to indemnify the successful party for the expenses it has been made to pay in order to initiate or defend the litigation, in practice only a portion of the costs are recoverable. There are two basic costs orders which can be awarded by a court: Party and party costs, which are the necessary and proper costs which have been incurred by the successful party. This is the most common award given; and Attorney and client costs, which allows for the recovery of more costs than party and party costs and is usually a punitive award. A notice of intention to tax must then be delivered to the other party. This notice will inform the opposing party that it has 10 days to inspect the documents or notes pertaining to each item on the bill and 20 days to file a notice of intention to oppose the bill. If no such notice is given within the prescribed time period then the matter may be set down for taxation before a Taxing Master without further notice to the opposing party. If the bill is opposed then a notice of taxation must be sent to the opposing party to inform them of the date and time on which the bill will be taxed before the Taxing Master. At the taxation of the bill of costs, the Taxing Master will go through each item, with reference to the tariff, and decide whether it should be allowed, disallowed or reduced. What is allowed by a Taxing Master is usually very significantly lower than the actual costs incurred. This is due to the tariff being outdated and bears little relation to the rates charged by most attorneys and because certain costs are not recoverable under the tariff. In order to determine the costs due to the successful litigant, a bill of costs must be drawn up. This can be done by an attorney or by a costs consultant. Generally it is more cost effective for a cost consultant to draw up the bill. A cost consultant will usually charge a percentage of the total of the drawn up bill. The bill of costs will, depending on the order granted, set out all of the costs incurred by the litigant from the inception of the matter to its finality. This includes attorney’s fees and disbursements such as counsel’s fees. The bill is drawn in accordance with a High Court tariff which provides for a set amount which can be claimed in respect of each item included in the bill of costs (e.g. there is a maximum amount allowed for drafting a letter or making a telephone call, and a fixed hourly rate at which attorneys fees can be recovered). Once the bill of costs has been drawn it is sent to the opposing party. The opposing party can then decide whether it wants the bill to be taxed before the Taxing Master of the High Court or whether it is wants to settle the claim for costs, either in full or by negotiation. This will sometimes happen when the opposing side does not wish to incur the additional costs associated with taxation. 15 Judgment granted Defended Action Proceedings LEAVE TO APPEAL REFUSED Summons Notice of intention to defend (10 days) End of case summary of judgment (15 Days) Warrant OF EXECUTION LEAve to defend APPLICATION to sca/CC further pleadings (10 days) discovery and other pre-trial procedures Trial LEAVE TO APPEAL GRANTED APPLICATION REFUSED APPEAL DISMISSED APPEAL UPHELD End of case Warrant OF EXECUTION End of case plea and counterclaim (20 days) replication and plea to counterclaim (15 days) 16 APPLICATION FOR LEAVE TO APPEAL (15 days) WARRANT OF EXECUTION Claim dismissed APPLICATION FOR LEAVE TO APPEAL (15 days) End of case LEAVE TO APPEAL REFUSED End of case APPLICATION to sca/CC LEAVE TO APPEAL GRANTED APPLICATION REFUSED APPEAL DISMISSED APPEAL UPHELD End of case End of case Warrant OF EXECUTION 17 Basic overview of Litigation in the High Court – Opposed Motion Proceedings Judgment granted APPLICATION FOR LEAVE TO APPEAL (15 days) WARRANT OF EXECUTION LEAVE TO APPEAL REFUSED APPLICATION to sca/CC LEAVE TO APPEAL GRANTED NOTICE OF INTENTION TO OPPOSE (5 days) APPLICATION REFUSED APPEAL UPHELD APPEAL DISMISSED ANSWERING AFFIDAVIT (15 days) End of case End of case Warrant OF EXECUTION NOTICE OF MOTION AND FOUNDING OF AFFIDAVIT End of case REPLYING AFFIDAVIT Claim dismissed NOTICE OF SET DOWN APPLICATION FOR LEAVE TO APPEAL (15 days) End of case Hearing LEAVE TO APPEAL REFUSED End of case 18 APPLICATION to sca/CC LEAVE TO APPEAL GRANTED APPLICATION REFUSED APPEAL UPHELD APPEAL DISMISSED End of case Warrant OF EXECUTION End of case 19 BW 3666 Antananarivo Tel +261 20 224 3247 Fax +261 20 224 3248 Email info@jwflegal.com www.jwflegal.com Cape Town Tel +27 21 480 7800 Fax +27 21 480 3200 Email cpt_info@bowman.co.za www.bowman.co.za Dar es Salaam Tel +255 22 277 1885 Fax +255 22 277 1886 Email info@ealc.co.tz www.ealawchambers.com Gaborone Tel +267 391 2397 Fax +267 391 2395 Email info@bookbinderlaw.co.bw www.bookbinderlaw.co.bw Johannesburg Tel +27 11 669 9000 Fax +27 11 669 9001 Email info@bowman.co.za www.bowman.co.za Kampala Tel +256 41 425 4540 Fax +256 31 226 3757 Email afmpanga@afmpanga.co.ug www.afmpanga.co.ug Nairobi Tel +254 20 289 9000 Fax +254 20 289 9100 Email ch@coulsonharney.com www.coulsonharney.com

![[2012] NZEmpC 75 Fuqiang Yu v Xin Li and Symbol Spreading Ltd](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008200032_1-14a831fd0b1654b1f76517c466dafbe5-300x300.png)