EVIDENCE LAW-Boundaries, Balancing, and Prior Felony

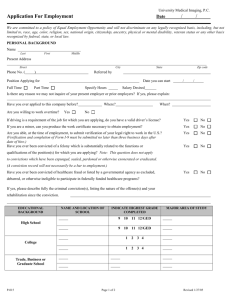

advertisement