PARTNERSHIP ACTS, 1891 to 1965

advertisement

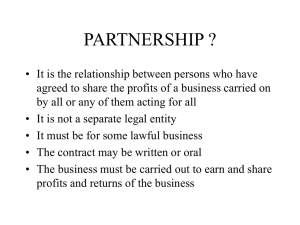

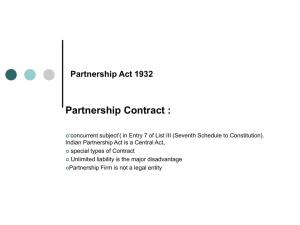

415 THE PARTNERSHIP ACTS, 1891 to 1965 Partnership Act of 1891, 55 Vic. No. 7 Amended by Statute Law Revision Act of 1908, 8 Edw. 7 No. 18 Decimal Currency Act of 1965, No. 61, s. 11, Second Schedule An Act to Declare and Amend the Law of Partnership [Assented to 31 August 1891] 1. Short title. This Act may be cited as "The Partnership Act of 1891." Collective title conferred by Act of 1965, No. 61, s. 11, Second Schedule. 2. Commencement of Act. This Act shall come into operation on the first day of January, one thousand eight hundred and ninety-two. 3. Interpretation clause. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, ss. 4, 45. In the interpretation of this Act, unless the context otherwise requiresThc term "Court" includes every court and judge having jurisdiction in the case; The term "Business" includes every trade, occupation, or profession; Persons who have entered into partnership with one another are for the purposes of this Act called collectively a firm, and the name under which their business is carried on is called the firm-name. Act referred to: Partnership Act, 1890; see 17 Halsbury's Statutes of England, 2nd ed., p. 579. A Magistrates Court has no jurisdiction to make a charging order under s. 26. See R. v. Hisizofl, [1907] SI. R. Qd. 28; [1907] Q.W.N. 9; 1 Q.l.P.R. 3. As to "business," see Rolls v. Miller (1884), 27 Ch. D. 71; [1881-5] All E.R. Rep. 915; Commissioners of Inland Revenue v. Marine Steam Turbine Co. Ltd., [1920] 1 K.B. 193. A firm-name must not end with the word "limited," Companies Acts, 1961 to 1964, s. 377, title COMPANIES, Vol. 2, p. 407. As to registration of firm-names, see Business Names Acts, 1962 to 1965, title MERCANTILE LAW, Vol. 12, p. 57. A partner carrying on the business by agreement after dissolution is entitled, in the absence of agreement to the contrary, to use the old firm-name so long as he does not do so in such a manner as to mislead persons into the belief that the retired partner is still a member of the firm, Scott v. Bail, [1914] V.L.R. 270. 4. (Repealed.) Repealed by Statute Law Revision Act of 1908, s. 2. 416 PARTNERSHIP Vol. 13 NATURE OF PARTNERSHIP 5. Definition of partnership. S3 & S4 Vic. c. 39, s. 1. (1) Partnership is the relation which subsists between persons carrying on a business in common with a view of profit. (2) But the relation between members of any company or association which is(a) Registered as a company under "The Companies Act 1863," or any other Act of Parliament for the time being in force and relating to the registration of joint stock companies; or (b) Formed or incorporated by or in pursuance of any other Act of Parliament or letters patent, or Royal Charter: is not a partnership within the meaning of this Act. (3) A limited partnership formed under the provISIOns of "The Mercantile Act of 1867" is a partnership within the meaning of this Act, and the rules of law declared by this Act apply to such a limited partnership except so far as the express provisions of that Act are inconsistent with such rules. Act referred to: Companies Act, 1R63; see now Companies Acts, 1961 to 1964, title COMPANIES, VoL 2, p, 31, For "bmincss," see s, 3, As to registration of firm names, see Business Name~ Act~, 1962 to 1965, title MFRCA~TILE LAW, Vol. 12, p, 57, Where a party to legal proceedings desires to put in issue the alleged constitution of a partnership he must do so specifically, R's,c' (l900), Order 25, rule 5, title SUPREME COURT. Partner~hip is constituted by the actual carrying on of a business, not by an agreement to c:my it on. Gahriel v. Evill (1842), 9 M. & W. 297; Re Young; Ex parle JOIlCS, [I R96] 2 Q.B. 484. As to the distinction between a partnership and a company, see Smith v. Anderson (1880). 15 Ch. D. 247; [1874-80] All E.R. Rep. 1121; Birch v. Cropper; Re Bridgewater Navigation Co. Ltd. (1889), 14 App. Cas. 525; [1886-90] All E.R. Rep. 628: and as to the nature of partnership generally, see 36 English and Empire Dige,t. (Rpl.) 423; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 483. A partnership must not consist of more than twenty persons for any business having as its object the acquisition of gain, Companies Acts, 1961 to 1964, s. 14, title COMPANIES, Vol. 2, p. 52. As .to partnership in a betting business, see Jeffrey v. Bamford, [1921] 2 K.B. 35 J. A partnership formed for an illegal purpose is void, Armstrong v. Lewis (1834). 2 Cr. & M. 274; and the courts will not recognise it or enforce any rights ",hich the supposed partners would otherwise have; see per McCardie, J., in Jeffrey v. Bamford, supra. And see the cases collected in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.). p. 450. Mining syndicates were held to be partnerships in WilliamoJ v. Rohinsoll (1890), 12 L.R.(N.S.W.) (Eq.) 34, and Folk v. Woolf, [1933] V.L.R. 403. But see Little v. McDonald (1883), 1 Q.L.J. 124. Mere promoters of a company are not partners, Wilkins v. Davies (1890), 16 V.L.R. 70. "There is nothing in English law which disable~ an infant from being a partner" Hawkins and Sunderland v. Duche & Sons (1921), 90 L.J.K.B. 913; and see the cases collected in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.), p. 451. Limited partnerships are provided for by the Mercantile Acts, 1867 to 1896 ss. 53-68, title MERCANTILE LAW, Vol. 12, p. 128. A limited partnership may be dissolved by the court under this Act notwithstanding that the time limited for continuance of such partnership in the registered certificate has not arrived, GroveJ v. Mathea (1898), 9 Q.L.J. 32. PARTNERSHIP ACTS, 1891 TO 1965 ss. S, 6 417 6. Rules for determining existence of partnership. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 2. In determining whether a partnership does or does not exist, regard shall be had to the following rules:(1) Joint tenancy, tenancy in common, joint property, common property, or part ownership does not of itself create a partnership as to anything held or owned jointly or in common, whether the tenants or owners do or do not share any profits made by the use thereof; (2) The sharing of gross returns does not of itself create a partnership, whether the persons sharing such returns have or have not a joint or common right or interest in any property from which or from the use of which the returns are derived; (3) The receipt by a person of a share of the profits of a business is prima facie evidence that he is a partner in the business, but the receipt of such a share, or of a payment contingent on or varying with the profits of a business, does not of itself make him a partner in the business; and in particular(a) The receipt by a person of a debt or other liquidated amount by instalments or otherwise out of the accruing profits of a business does not of itself make him a partner in the business or liable as such; (b) A contract for the remuneration of a servant or agent of a person engaged in a business by a share of the profits of the business does not of itself make the servant or agent a partner in the business or liable as such; (c) A person being the widow or child of a deceased partner, and receiving by way of annuity a portion of the profits made in the business in which the deceased person was a partner, is not by reason only of such receipt a partner in the business or liable as such; ( d) The advance of money by way of loan to a person engaged or about to engage in any business on a contract with that person that the lender shall receive a rate of interest varying with the profits, or shall receive a share of the profits arising from carrying on the business, does not of itself make the lender a partner with the person or persons carrying on the business or liable as such: Provided that the contract is in writing, and signed by or on behalf of all the parties thereto; (e) A person receiving by way of annuity or otherwise a portion of the profits of a business in consideration of the sale by him of the goodwill of the business is not by reason only . of such receipt a partner in the business or liable as such. II contract Whether a partnership does or does not exist depends on the intention and of the parties, Mol/wo, March Co. v. Court of Wards (1872), L.R. 4 & P.c. 419; and the cases collected in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.), p. 426; and without an intention to become partners a partnership cannot be constituted, Sutton & Co. v. Grey, [1894] 1 Q.B. 285, at p. 287. That .the term "partner" is not employed is immaterial, Greenham v. Gray (1855), 4 Ir. C.L. 501; so is the fact that expressions denoting partnership are avoided, Adam v. Newbigging (1888), 13 App. Cas. 308, 315. The real test of the existence of a partnership is whether the persons are carrying on business as principals and agents for each other, Ballons v. Kleineg. [1925] S.A.S.R. 227. 14 418 PARTNERSHIP Vol. 13 The way in which the parties acted, and the way in which the accounts were kept, are matters to be considered, Re Hulton, Hulton v. Lister (1890), 62 L.T. 200, 204; McKenzie v. McKenzie, [1921] N.Z.L.R. 319. As to what constitutes a partnership, see also Barker v. Law, [1919] St. R. Qd. 152; [1919] Q.W.N. 31 (agreement by owner of farm with another to work the farm together for a period); Wilson v. Carmichael (1904), 2 C.L.R. 190; !lal'age v. Union Bank oj Australia Ltd. (1906), 3 C.L.R. 1170 (executors carrying on business of testator); Lang v. James Morrison & Co. Ltd. (1911). 13 C.L.R. 1; Sefton v. Dickson (1884),2 Q.L.J. 33. Paragraph (1 )-With respect to land purchased by co-owners of land, not partnership property, out of the profits of such land made by them as partners, see s. 23 (3). Joint purchase, with a view to resale and division of the profits. constitutes partnership; joint purchase with a view to division of the thing purchased ~oes not, Reid v. Hollinshead (1825), 4 B. & C. 867; Gihson v. Lupton (1832), 9 Bing. 297. See also the cases in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.), p. 427. Paragraph (2)-See the cases collected in 36 English and Empire Digest. (Rp!.), p. 432. Paragraph (3)-This paragraph embodies .the principle laid down in the leading case of Cox v. Hickman (1860), 8 H.L. Cas. 268. If the only fact known is that profits are shared there is prima facie evidence of partnership, Badeley v. Consolidated Bank (1888), 38 Ch. D. 238, 258; but the receipt of a share of profits does not create a presumption of partnership which must be rebutted by other circumstances; all of the circumstances must be considered, and an inference drawn from them as a whole. without attributing undue weight to anyone of them. Davis v. Davis. [1894] 1 Ch. 393; Re Young; Ex parte Jones, [18961 2 Q.B. 484. For a case where persons sharing profits were held not to be partners, see Re Buchanan & Co. (1876), 4 S.C.R. 202; I Q.L.R. Part I, 67. The relationship of master and servant may exist between persons who are partners in the undertaking wherein the employment takes place, Willmer v. Sleight (1911), 5 Q.J.P.R. 164; [1912] Q.w.N. 2. Division (d) of paragraph (3) applies only when there is a real loan, Pooley v. Driver (1876), 5 Ch. D. 458, 485; an unsigned contract is not a contract in writing within the paragraph (ibid.). p. 468. The test is "is the business carried on for the benefit of the lender," King & Co. v. WhichelolV (1895). 64 L.J.Q.B. 801, at p. 806. Stipulations as to not carrying on any other business. and as to keeping accounts and not giving credit, are consistent with the relation of lender and borrower, and do not take a case out of the protection of paragraph (3) (d), Ex parte Jones; Re Butchart (1865), 2 W.W. & a'B. (I.) 8. See on paragraph 3 of this section Lopes v. Marino, [1939J S.R.(N.S.W.) 188: Wiltshire v. Kuenzli (1946), 63 W.N.(N.S.W.) 47; Miles v. Clarke, [1953] I All E.R. 779. See also 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 485. 7. Postponement of rights of person lending or selling in consideration of share of profits in case of insolvency. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 3. In the event of any person to whom money has been advanced by way of loan upon such a contract as is mentioned in the last preceding section, or of any buyer of a goodwill in consideration of a share of the profits of the business, being adjudicated insolvent, entering into an arrangement to pay his creditors less than one hundred cents in the dollar, or dying in insolvent circumstances, the lender of the loan shall not be entitled to recover anything in respect of his loan, and the seller of the goodwill shall not be entitled to recover anything in respect of the share of profits contracted for, until the claims of the other creditors of the borrower or buyer for valuable consideration in money or money's worth have been satisfied. As amended by Act of 1965, No. 61, s. 11, Second Schedule. Compare Bankruptcy Act 1924-1965, s. 86 (Commonwealth). PARTNERSHIP ACTS, 1891 TO 1965 ss.6-9 419 This section refers to s. 6 (3) (d), and applies whether the contract be oral or written, notwithstanding the proviso to s. 6 (3) (d), Re Fort; Ex parte Schofield, [1897] 2 Q.B. 495. It applies though the terms of the loan be subsequently al.tered, Re Hildcsheim; Ex parte The Trustee, [1893] 2 Q.B. 357; and it applies even after a partnership has been dissolved, Re Mason; Ex parte Bing, [1899] I Q.B. 810, 815; but it does not affect the rights of a mortgagee under his mortgage, Re Lonergan; Ex parte Sheil (1877), 4 Ch. D. 789; Badeley v. Consolidated Bank (1886), 34 Ch. D. 536; (1888), 38 Ch. D. 238. See 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 491. RELATIONS OF PARTNERS TO PERSONS DEALING WITH THEM 8. Power of partner to bind the finn. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 5. Every partner is an agent of the firm and his other partners for the purpose .' of the business of the partnership; and the acts of every partner who does any act for carrying on in the usual way business of the kind carried on by the firm of which he is a member bind the firm and his partners, unless the partner so acting has in fact no authority to act for the firm in the particular matter, and the person with whom he is dealing either knows that he has no authority, or does not know or believe him to be a partner. Compare s. II. With respect to liability of persons holding themselves out as partners, see s. 17. With respect to authority for winding-up purposes after dissolution, see s. 41. Where one partner has given notice that he will not be answerable, the person receiving notice must prove some act of adoption before he can make that partner liable, Willis v. Dyson (1816), I Stark 164. Where the act of the partner is not done for carrying on the firm's business in the usual way, the firm will be liable if ratification of the act can be inferred, Sandilands v. Marsh (1819), 2 B. & Ald. 673. A firm is not liable for the acts of a partner in dealing as an individual to the exclusion of the firm. See Polkinghorne v. Holland (1934), 51 C.L.R. 143. A partner in a non-trading firm has no implied authority to accept bills of exchange on behalf of the firm, Wheatley v. Smithers, [1906] 2 K.B. 321; [1907] 2 K.B. 684. With respect to the extent of the ordinary course of business of solicitors in relation to advising clients investing money, see Polkinghorne v. Holland, supra. The business of money-lending does not necessarily involve the borrowing of money so as to give one partner an authority to borrow on behalf of the firm, Mandelherg v. Adams (1930). 31 S.R.(N.S.W.) 50. As to authority of a member of a partnership carrying on the business of farming, see Molinas v. Smith, [1932] St. R. Qd. 77; 26 Q.J.P.R. 1. See generally 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 503; cases in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.) p. 460. 9. Partners bound by acts on behalf of firm. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 6. An act or instrument relating to the business of the firm and done or executed in the firm-name, or in any other manner showing an intention to bind the firm, by any person thereto authorised, whether a partner or not, is binding on the firm and all the partners. But this section does not affect any general rule of law relating to the execution of deeds or negotiable instruments. A partner cannot, without express authority. bind the firm by a submission to arbitration, Stead v. Salt (1825), 3 Bing. 101, by opening a banking account in his own name, Alliance Bank Ltd. v. Kearsley (1871), L.R. 6 C.P. 433, or by giving a guarantee, Brettel v. Williams (1849), 4 Exch. 623. For power to retain a solicitor. see Court v. Berlin, [1897] 2 Q.B. 396; Tomlinson v. Broadsmith, [1896] 1 Q.B. 386. An agent executing a deed in his own name is the only person who can sue or be sued thereon, Appleton v. Binks (1804), 5 East 148; Re International Contract Co., Pickerinr/s Claim (1871), 6 Ch. App. 525. 420 PARTNERSHIP Vol. 13 By s. 28 of the Bills of Exchange Act, 1909-1958 (Commonwealth), no person is liable on a bill of exchange (or promissory note; see s. 95 of the Act) who has not signed it; but the signing of the name of a firm renders all partners liable. See ibid., s. 91, as the liability,,!, two or more persons signing a promissory note. Though one of two partners is not as partner entitled to execute deeds on behalf of the partnership, yet an assignment by deed of a partnership debt by a partner is a good equitable assignment and binding on the partnership, though the deed is bad as a deed, Marchant v. Morton, Down & Co., [1901] 2 K.B. 829; Re Briggs & Co., Ex parte Wright, [1906] 2 K.B. 209. See generally 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), p. 460. 10. Partner using credit of firm for private purposes. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 7. Where one partner pledges the credit of the firm for a purpose apparently not connected with the firm's ordinary course of business, the firm is not bound, unless he is in fact specially authorised by the other partners; but this section does not affect any personal liability incurred by an individual partner. A belief that there was authority is not sufficient, Kendal v . Wood (1870). L.R. 6 Ex. 243. Although the purchase of farming land would not, in ordinary circumstances. be within the ordinary course of the business of farming, facts showing that it was contemplated by the partners will bring it within the section, Kennedy v. Malcolm Bros. (1909), 28 N.Z.L.R. 457. As to purchase of farm machinery. see Molillas v. Smith, [1932] St. R. Qd. 77; 26 Q.J.P.R. 1. See 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 507. 11. Effect of notice that firm will not be bound by acts of partner. .53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 8. If it has been agreed between the partners that any restriction shall be placed on the power of anyone or more of them to bind the firm, no act done in contravention of the agreement is binding on the firm with respect to persons having notice of the agreement. See also s. 8. 12. Liability of partners. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 9. Every partncr in a firm is liable jointly with the other partners for all debts and obligations of the firm incurrcd while he is a partner; and after his death his estate is also severally liable in a due course of administration for such debts and obligations, so far as they remain unsatisfied, but subject to the prior payment of his separate debts. For the liability of new and retiring partners, see s. 20. This section deals with liability ex contractu. Liability ex delicto is dealt with by s. 15. The estate of a deceased partner is not liable in an action for the price of goods sold and delivered, where delivery took place after his death, Bagel v. Miller, [1903] 2 K.B. 212. As to "debts and obligations," see Friend v. Young, [1897] 2 Ch. 421. Execution may be levied against the several partners jointly either on their joint property or on the separate property of anyone of more of them, or both on their joint or on .their respective separate properties, Re Reeves, [1918] N.Z.L.R. 376. See R.S.c. (1900), Order 54, rule 10, title SUPREME COURT. See generally the cases collected in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), p. 480; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 512. 13. Liability of the firm for wrongs. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 10. Where, by any wrongful act or omission of any partner acting in the ordinary course of the business of the firm, or with the authority of his co-partners, loss or injury is caused to any person not being a partner in the firm, or any penalty is incurred, the firm is liable therefor to the same extent as the partner so acting or omitting to act. PARTNERSHIP ACTS, 1891 TO 1965 ss.9·16 421 Liability is joint and several, see s. 15. The doing of a lawful thing by unlawful means is within the section, Hamlyn v. HOllston & Co., [1903] 1 K.B. 81. See also British Homes Assurance Corpn. Ltd. v. Paterson, [1902] 2 Ch. 404 (fraud committed before commencement of partnership; notice to plaintiff; election to treat with original partner alone); Tendring Hundred Waterworks Co. v. Jones, [1903] 2 Ch. 615 (transaction not within duties of partnership; secretaryship of company; acceptance of conveyances in own name); Hamlyn v. Houstoll & Co., [1903] 1 K.B. 81; and, generally, 3 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.), p. 131; Vo!' 36, pp. 476, 482; Vo!' 42, p. 373. There is an exception to this rule in s. 13 of the Statute of Frauds and Limitations of 1867, title FRAUDS, Vo!. 6, p. 207, which provides that no action shall be brought on any representation as to character or credit to the intent that a person may obtain money, credit or goods thereon unless it be made in writing and signed. But this applies only to fraudulent misrepresentations, Banbury v. Bank of Montreal, [1918] A.C. 626; [1918·19] All E.R. Rep. 1. It was held that a conviction for a summary offence should be against the partners individually, in Bishop v. Chung Bros. (1907). 4 C.L.R. 1262. See also 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 509. 14. Misapplication of money or property received for or in custody of the firm. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 11. In the following cases, namely:( 1) Where one partner acting within the scope of his apparent authority receives the money or property of a third person and misapplies it; and (2) Where a firm in the course of its business receives money or property of a third person, and the money or property so received is misapplied by one or more of the partners while it is in the custody of the firm; the firm is liable to make good the loss, Liability is joint and several, s. 15. The section does not apply when the defaulting partner, though acting within the scope of his authority, had not entered into the contract as a member of the firm, British Homes Assurance Corpn. Ltd. v. Paterson, [1902] 2 Ch. 404; Polkinghorne v. Holland (1934), 51 C.L.R. 143. See generally 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.), p. 482; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 513. As to "custody of the firm," see Tendring Hundred Waterworks Co. v. Jones, [1903] 2 Ch. 615. Where a trustee, who was a member of a legal firm, received money in the first instance as such trustee, and then in his other capacity as partner paJd such money to the credit of his firm's account to keep the partnership going, his co-partners, though innocent of the fraud, were held liable, Shannon v. Whiting (1901), 7 A.L.R. 49. As to the position where a person carrying on some business with a client takes a partner before that business is completed, see Hallinan v. Kinsey (1935), 35 S.R.(N.S.w.) 206. It is in the ordinary course of ,the business of a solicitor to receive moneys for investment in particular mortgages, Marwedel v. Hamilton and Garde, [1940] St. R. Qd. 191. 15. Liability for wrongs joint and several. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 12. Every partner is liable jointly with his co-partners and also severally for everything for which the firm while he is a partner therein becomes liable under either of the two last preceding sections. This section does not apply to breaches of trust. See s. 16. 16. Improper employment of trust property for partnership purposes. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 13. If a partner, being a trustee, improperly employs trust property in the business or on the account of the partnership, no other partner is liable for the trust property to the persons beneficially interested therein: 422 PARTNERSHIP Vol. 13 Provided as follows:( 1) This section does not affect any liability incurred by any partner by reason of his having notice of a breach of trust; and (2) Nothing in this section prevents trust money from being followed and recovered from the firm if still in its possession or under its control. Section 14 does not apply. because in cases of breach of trust the money docs not come into ,the firm's hands in the ordinary course of business; nor does s. 19, as to imputed notice. apply. The liability is joint and several, Blyth v. F/adgatc, [1891] 1 Ch. 337, 353. See generally the cases collected in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.), p. 483; 28 Halsbury's laws of England, 3rd ed .. p, 509. 17. Persons liable by "holding out." 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 14. (1) Everyone who by words spoken or written or by conduct represents himself, or who knowingly suffers himself to be represented, as a partner in a particular firm, is liable as a partner to anyone who has on the faith of any such representation given credit to the firm, whether the representation has or has not been made or communicated to the person so giving credit by or with the knowledge of the apparent partner making the representation or suffering it to be made: (2) Provided that, where after a partner's death the partnership business is continued in the old firm-name, the continued use of that name or of the deceased partner's name as part thereof does not of itself make his executors or administrators estate or effects liable for any partnership debts contracted after his death. See s. 39. as to rights against apparent members of a partnership. The liability is founded on estoppel, Mol/wo. March & Co. v. COllrt of Wards (1872). L.R. 4 P.c. 419. As to the grant of an injunction to restrain a holding out, see Walter v. Ashton, [1902] 2 Ch. 282. See also 36 English and Empire Digest. (Rpl.). p. 444; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 492. 18. Admissions and representations of partners. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 15. An admission or representation made by any partner concerning the partnership affairs, and in the ordinary course of its business, is evidence against the firm. Generally. as to admissibility in evidence of admissions made by partners. see 22 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.), p. 83; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 511. 19. Notice to acting partner to be notice to tbe firm. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 16. Notice to any partner who habitually acts in the partnership business of any matter relating to partnership affairs operates as notice to the firm, except in the case of a fraud on the firm committed by or with the consent of that partner. Notice of dishonour of a bill of exchange given continuing partner is notice to a retired partner, Goldfarb [1920] 1 K.B. 639. Notice to a person before he becomes a partner is Williamso!! v. Barbour (1877), 9 Ch. D. 529, 535. Notice to a clerk may be notice to the firm, John v. A.c. 56~. 568. after dissolution to a v. Bartlett and Kremer, not notice to the firm, Dodwell & Co., [1918] PARTNERSHIP ACTS, 1891 TO 1965 ss.16-23 423 20. Liabilities of incoming and outgoing partners. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 17. (1) A person who is admitted as a partner into an existing firm does not thereby become liable to the creditors of the firm for anything done before he became a partner. (2) A partner who retires from a firm does not thereby cease to be liable for partnership debts or obligations incurred before his retirement. (3) A retiring partner may be discharged from any existing liabilities by an agreement to that effect between himself and the members of the firm as newly constituted and the creditors, and this agreement may be either express or inferred as a fact from the course of dealing between the creditors and the firm as newly constituted. If it clearly appears that no partnership existed at the time of the contract, no subsequent act by a person who may afterwards become a partner will make him liable on the contract, Saville v. Roberston (1792), 4 Term Rep. 720. See 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.), p. 484. The burden of proving that liability has ceased is on the retired partner, VulJiamy v. Noble (1817), 3 Mer. 593. A creditor may, in certain circumstances, be estopped from holding the retired partner liable, Davison v. Donaldson (1882), 9 Q.B.D. 23. A creditor who treats the remaining partners as his debtors does not necessarily absolve the retired partner from liability, Lodge v. Dicas (1820), 3 B. & Ald. 611; David v. Ellice (1826), 5 B. & C. 196; Smith v. Patrick, [1901] A.C. 282, but the retired partner may cease to be a principal debtor and become a surety, and be discharged by time being given to the continuing partner, Goldfarb v. Bartlett and Kremer, [1920] I K.B. 639. See generally, as to the duration of liability, 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.) p. 484; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed .. p. 514. As to novation, see 12 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.), p. 669; Vol. 36, p. 495. 21. Revocation of continuing guaranty by change in firm. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 18. 31 Vic. No. 22, s. 7. A continuing guaranty given either to a firm or to a third person in respect of the transactions of a firm is, in the absence of agreement to the contrary, revoked as to future transactions by any change in the constitution of the firm to which, or of the firm in respect of the transactions of which, the guaranty was given. See National Mortgage and Agency Co. of N.z. Ltd. v. Tait, [1929] N.Z.L.R. 235; 26 English and Empire Digest, (Rp\.) pp. 179. 213; 18 Halsbury's Laws of England (3rd ed.), p. 459. RELATIONS OF PARTNERS TO ONE ANOTHER 22. Variation by consent of terms of partnership. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 19. The mutual rights and duties of partners, whether ascertained by agreement or defined by this Act, may be varied by the consent of all the partners, and such consent may be either express or inferred from a course of dealing. The variation may bind a new partner, Const v. Harris (1824), Turn. & R. 496. 23. Partnership property. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 20. (1) All property and rights and interests in property originally brought into the partnership stock or acquired, whether by purchase or otherwise, on account of the firm, or for the purposes and in the course of the partnership business, are called in this Act partnership property, and must be held and applied by the partners exclusively for the purposes of the partnership and io accordance with the partnership agreement: 424 PARTNERSHIP Vol. 13 (2) Provided that the legal estate or interest in any land which belongs to the partnership shall devolve according to the nature and tenure thereof, and the general rules of law thereto applicable, but in trust, so far as necessary, for the persons beneficially interested in the land under this section. (3) Where co-owners of an estate or interest in any land not being itself partnership property are partners as to profits made by the .use. of that land, and purchase other land out of the profits to be used III lIke manner, the land so purchased belongs to them, in the absence of an agreement to the contrary, not as partners, but as co-owners for the same respective estates and interests as are held by them in the land first mentioned at the date of the purchase. Land which is partnership property is treated as personal estate as between the partners, s. 25. As to the application of partnership property on dissolution, see ss. 42-44. The interest of a partner in the partnership property is an equitable interest and may be assigned without consideration, AIming v. Anning (1907), 4 C.L.R. 1049; Col/ill.~ v. Col/ins, [1911] St. R. Qd. 241; [1911] Q.W.N. 53. See 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.), p. 537. For criminal liability of partners for acts done with respect to partnership property, see Criminal Code, ss. 34, 396, title CRIMINAL LAW, Yo!. 3, pp. 248, 409. Subsection (1 )-See Carter Bros. v. Renol/f, [1963] A.L.R. 46; 36 A.L.J.R. 67. See Butler v. Madden (1941),4 S.R.(N.S.W.) 245 (presumption that property bought with partnership money is partnership property displaced by agreement between partners; purchase of lands; partnership in proceeds of lands rather ,than in lands themselves). As to removal of partnership property by bankrupt partner, see R. v. Edwards, [1948] Q.W.N. 26. 24. Property bought with partnership money. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 21. Unless the contrary intention appears, property bought with money belonging to the firm is deemed to have been bought on account of the firm. Property purchased in the name of one partner out of the funds of the firm is partnership property, Forster v. Hale (1800). 5 Yes. 308; Smith v. Smith (1800), 5 Yes. 189, 193; Wray v. Wray, [1905] 2 Ch. 349; and similarly property obtained by a partner in breach of faith to the partnership will be treated as obtained for the benefit of the partnership. Gordon v. Scott (1858), 12 Moo. P.e. 1; Re North Australian Territory Co. (Archer's Case), [1892] 1 Ch. 322. The presumption that the property was acquired on account of the firm may be rebutted, Smith v. Smith (1800), 5 Yes. 189. See generally, as to property purchased with partnership money, the cases in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.), p. 537; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 530. 25. Conversion into personal estate of land held as partnership property. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 22. Where land has become partnership property, it shall, unless the contrary intention appears, be treated as between the partners (including the representatives of a deceased partner), and also as between the representatives of a deceased partner, as personal and not real estate. This section only applies in the absence of any intention to the contrary, Re Wilson, Wilson v. Hal/away, [1893] 2 Ch. 340. A deceased partner's interest in land belonging to the partnership was treated as personalty for purposes of death duty, In the Will of Butler, [1915] Q.W.N. 5. Land which is intended to remain vested in partners as tenants in common but not to form part of the assets of the partnership is not to be treated as personal estate, Meyenherg v. Pattison (1890), 3 Q.L.J. 184. PARTNERSHIP ACTS, 1891 TO 1965 ss.23-26 425 An agreement for a partnership which provided that land to be acquired by the partners should be held in equal shares, but not providing for the transfer of any interest in land, was held not to be an agreement which was required to be in writing by s. 5 of the Statute of Frauds and Limitations of 1867, title FRAUDS, Vol. 6, p. 208, Williams v. Hartin (1899), 1 N. & S. 132. See also Caporn v. Dixon (1904), 6 W.A.L.R. 71. This section does not convert land into personalty for purposes of doing away with the necessity of a written memorandum of a sale of the interest of a partner in such land, Meyenberg v. Pattison, supra. See also 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), p. 537; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 532. 26. Procedure against partnership property for a partner's separate judgmeut debt. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 23. (1) After the commencement of this Act a writ of execution shall not issue against any partnership property except on a judgment against the firm. (2) The court may, on the application by summons of any judgment creditor of a partner, make an order charging that partner's interest in the partnership property and profits with payment of the amount of the judgment debt and interest thereon, and may by the same or a subsequent order appoint a receiver of that partner's share of profits (whether already declared or accruing), and of any other money which may be coming to him in respect of the partnership, and direct all accounts and inquiries, and give all other orders and directions which might have been directed or given if the charge had been made in favour of the judgment creditor by the partner, or which the circumstances of the case may require. (3) The other partner or partners shall be at liberty at any time to redeem the interest charged, or in case of a sale being directed, to purchase the same. With respect to execution on a judgment against a firm, see R.S.C. (1900), Order 54, ruk 10, title SUPREME COURT. As to "the court," see s. 3. A Magistrates Court cannot make a charging order under this scclion. See R. v. HiS/IOn, [1907] St. R. Qd. 28; [1907] Q.W.N. 9; 1 Q.1.P.R. 3. For practice on applications under this section, see R.S.C. (1900), Order 50, rules 5·7, title SUPREME COURT. Parin;;.-s who have entered up judgment against another partner can pursue the remedy under this section, which is not restricted to creditors other than par.tners, l.olllux v. Allstin (1913), 32 N.Z.L.R. 1181. Where I he judgment debtor assigns his interest in the partnership before the hearing of the summons, the court has no power to make an order, Brown v. Morrison (1899), 16 W.N.(N.S.W.) 124. A charging order cannot be refused on the ground that the amount of the judgment is small, Wilson v. Green (1918), 14 Tas. L.R. 40. A court will not make an order unless proof is given that all other means of enforcing the judgment are exhausted, Frunklin v. Ruck (1899), 2 N.Z.O.L.R. 45. An order directing the other partners to render an account will be granted only in special circumstances, Brown, Janson & Co. v. Hutchinson & Co., [1895] 2 Q.B. 126. Partners purchasing must act with good faith, Perens v. Johnson (1857), 3 Sm. & O. 419. Otherwise the sale will he set aside, He/more v. Smith (1887), 35 Ch. D. 436. A charging order gives the creditor no greater rights than the debtor had, Cooper v. Griffin, [1892] 1 Q.B. 740. A charging order is a ground for dissolution, s. 36 (2). See also 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), p. 524; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 544. 426 PARTNERSHIP Vol. 13 27. Rules as to interests and duties of partners subject to special agreement. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 24. The interests of partners in the partnership property and their rights and duties in relation to the partnership shall be determined, subject to any agreement express or implied between the partners, by the following rules:( 1) All the partners are entitled to share equally in the capital and profits of the business, and must contribute equally towards the losses whether of capital or otherwise sustained by the firm. (2) The firm must indemnify every partner in respect of payments made and personal liabilities incurred by him(a) In the ordinary and proper conduct of the business of the firm; or (b) In or about anything necessarily done for the preservation of the business or property of the firm. (3) A partner making, for the purpose of the partnership, any actual payment or advance beyond the amount of capital which he has agreed to subscribe, is entitled to interest at the rate of six per cent. per annum from the date of the payment or advance. ( 4) A partner is not entitled, before the ascertainment of profits, to interest on the capital subscribed by him. (5) Every partner may take part in the management of the partnership business. (6) No partner shall be entitled to remuneration for acting in the partnership business. (7) No person may be introduced as a partner without the consent of all existing partners. (8) Any difference arising as to ordinary matters connected with the partnership business may be decided by a majority of the partners, but no change may be made in the nature of the partnership business without the consent of all existing partners. (9) The partnership books are to be kept at the place of business of the partnership (or the principal place, if there is more than one), and every partner may, when he thinks fit, have access to and inspect and copy any of them. There was held to be an implied agreement that before distribution of capital one partner should be repaid a sum provided by him as initial capital, in Kelly v. Tucker (1907), 5 C.L.R. 1. Paragraph (1 )-See also s. 47, as to distribution of partnership assets. In Stewart v. Forbes (1849), 1 Mac. & G. 137, inequality was inferred from the books and the course of dealing. The rule as to equality applies to partners in a single transaction, Rohinson v. Anderson (1855), 20 Beav. 98. In Warner v. Smith (1863), 1 De G.J. & Sm. 337, where a firm entered into partnership with another person, the firm was held to be entitled to only half the profits. As to the meaning of "profits," see Re Spanish Prospecting Co. Ltd., [1911] 1 Ch. 92; [1908-10] All E.R. Rep. 573. The inference is that losses are to be shared in the same proportion as profits, Re Albion Life Ass. Soc. (1880), 16 Ch. D. 83. See generally 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), p. 554; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., pp. 534, 536. PARTNERSHIP ACTS, 1891 TO 1965 ss.27-29 427 Paragraph (2)-As to payments and liabilities to which the right of indemnity extends, see 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), p. 550; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 541. For an illustration of agreement modifying the operation of paragraph 2, see Turner v. Webb (1942), 42 S.R.(N.S.W.) 68 (where in a partnership action the liability of [he partners was limited to the respective amounts represented by their shares). See also Sing Hoy Luw v. Lee Foy and Others, [1943] Q.W.N. 35; Re Nuunan, [1949] St. R. Qd. 62. Paragraph (3 )-An agreement to pay a different rate of intere,t may be inferred from the circumstances, see Re Magdalella Steam Navigation Co. (1860), lohn 690. See the cases collected in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), p. 56l. Paragraph (4 )-Interest between partners is not allowed unless there be an express stipulation or a course of practice to the contrary, Rishton v. Grissell (1868), L.R. 5 Eq. 326. Interest cannot he claimed for a period subsequent to dissolution, Watney v. Wells (1867), 2 Ch. App. 250. Paragraph (6)-This rule applies though one partner does more work than the other, Robinson v. Andersun (1855),20 Beav. 98. It would seem that in special circumstances, e.g., where one partner discontinues work, the working partner may be entitled to remuneration, Airey v, Barham (1861), 29 Beav. 620. See generally the cases collected in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), p. 5 and 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 528. Paragraph (7)-With respect to assignment of a partner's interest, see s. 34. See 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), p. 533; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 528. Paragraph (8)-For cases in which the consent of alI the partners is required, see also 5S. 22, 27 (7), 28 of this Act. In Highley v. Walker (1910), 26 T.L.R. 685, the admission into the partnership works of a son of one partner was held .to be an "ordinary matter." Where two partners are divided, the one in favour of the existing state of things prevails, Donaldson v. Williams (1833), 1 Cr. & M. 345. The majority mList act bona fide, COllst V. Harris (1824), Turn. & R. 496, 518, See generally the cases collected in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), pp. 530 et seq., and see 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., pp. 527 et seq. Paragraph (9 )-A partner may appoint an agent to inspect the books, Bevan v. Webb, [1901] 2 Ch. 59; [1900-3] All E.R. Rep. 206; unless the agent is open to objection cf. Dadsll'cll v. Jacobs (1887), 34 Ch. D. 278; but names may not be extracted for an improper purpose, Trego v. Hunt, [1896] A.c. 7; [1895-9] All E.R. Rep. 804. See also the cases in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), pp. 563, 600, and 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 536. Other Cases-As to when one partner may sue another for breach of the partnership agreement, see SheafJe v. Hungerford (1879), 1 Q.L.l. Supp. 51. As to actions between a firm and one or more of its members, see H..S.C. (1900), Order 54, rule 12, title SUPREME COURT. Where a partnership action has been rendered necessary by the negilgence or other misconduct of a party, he may be ordered to pay the costs, Clark v. Mogg (1896), 7 Q.L.1. (N.C.) 51. 28. Expulsion of partner. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 25. A majority of the partners cannot expel a partner unless a power to do so has been conferred by express agreement between the partners. Where articles give the majority a power to expel, such power must be exercised bona fide, Biisset v. Daniel (1853), 10 Hare 493; Carmichael v. Evans, [1904] 1 Ch. 486. And see 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), pp. 609, 611, and 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 564. 29. Retirement from partnership at will. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 26. ( 1) Where no fixed term has been agreed upon for the duration of the partnership, any partner may determine the partnership at any time on giving notice of his intention so to do to all the other partners. 428 PARTNERSHIP Vol. 13 (2) Where the partnership has originally been constituted by deed, a notice in writing, signed by the partner giving it, is sufficient for this purpose. See also s. 35 (3). The notice may be prospective, Mellersh v. Keen (1859), 27 Beav. 236, bu.t cannot be withdrawn except with consent, Jones v. Lloyd (1874), L.R. 18 Eq. 265. Dissolution may be inferred from the circumstances, Pearce v. Lindsay (1860), 3 De 0.1. & Sm. 139. See 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 562. 30. Where partnership for term is continued over, continuance on old terms presumed. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 27. (1) Where a partnership entered into for a fixed term is continued after the term has expired, and without any express new agreement, the rights and duties of the partners remain the same as they were at the expiration of the term, so far as is consistent with the incidents of a partnership at will. (2) A continuance of the business by the partners or such of them as habitually acted therein during the term, without any settlement or liquidation of the partnership affairs, is presumed to be a continuance of the partnership. As to dissolution upon expiration of a fixed term, see s. 35 (1). See 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), p. 457; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 502. For power of the Public Curator to dissolve a partnership as representing a mentally sick person, see Mental Health Acts, 1962 to J 964, s. 46; Third Schedule, clause 25, title MENTAL HEALTH, Vol. 11, pp. 746, 769. 31. Duty of partners to render accounts, etc. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 28. Partners are bound to render true accounts and full information of all things affecting the partnership to any partner or his legal representatives. As to the right of a partner to have the accounts of the partnership taken by the court, see WilSall v. Carmichael (1904), 2 C.L.R. 190; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 549. The fact that one partner refuses to dissolve, or admit a dissolu.tion, is immaterial to the right to have an account taken by the court, Queensland Trustees Ltd. v. FalVckner, [1964] Qd. R. 153. For an action brought for an account of .the goodwill of a partnership, see Brown v. POtier, [1965] Qd. R. 268. The court ordered accounts to be taken separately and simultaneously at two places at which the partnership business was carried on under different firm names Hoyer v. Tiegs, [1902] Q.W.N. 39. ' The general rule is that costs of an action for dissolution and taking of a partnership account are to be borne by the partnership estate unless there is good reason to order one or other party to bear them, and where there appears to have beep no material whatsoever upon which to found the exercise of a discretion, prima faCie an order that the defendant pay the plaintiff's costs is wrong Queensland ' Trustees Ltd. v. Fawckller, [1964] Qd. R. 153. . See generally, as to the duty of partners to account, 36 English and Empire DIgest (Rpl.), p. 527. 32. Accountability of partners for private profits. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 29. (1) Every partner must account to the firm for any benefit derived by him. without the con~ent of the other partners from any transaction concernmg the partnershIp, or from any use by him of the partnership property name or business connection. PARTNERSHIP ACTS, 1891 TO 1965 ss.29-34 429 (2) This section applies also to transactions undertaken after a partnership has been dissolved by the death of a ~artner, and befor~ ~he affairs thereof have been completely wound up, elther by any survlvmg partner or by the representatives of the deceased partner. For criminal liability of partners receiving bribes, see Criminal Code, ss. 442A et seq., title CRIMINAL LAW, Vol. 3, p. 440. If a partner obtains a renewal of a lease of the partnership property, the lease is an asset of the firm, Featherstonhaugh v. Fenwick (1810), 17 Ves. 298. A partner is entitled to purchase partnership property at a sale by a mortgag.ee withou.t any obligation to hold the property as purchased for the partnership, King.wnill v. Lyne (1910), 13 C.L.R. 292. See also Wicks v. Bennett (1921), 30 C.L.R. 80 (purchase by partner of freehold of property subject to lease to firm). A portion of the profits of a sale received without the consent of the other partner by a member of a partnership of estate agents which had conducted the sale, was held to belong to the partnership, Birtchnell v. Equity Trustees, Executo,:s and Agency Co. Ltd. (1929), 42 C.L.R. 384. Where debtors of a partnership assigned their estate to trustees of whom defendant, a partner, was one, and defendant purchased the whole estate for his own benefit, he was held liable to account, Gibson v. Tyree (1900), 20 N.Z.L.R. 278. In Fleming v. McKechnie and McMillan (1905), 25 N .Z.L.R. 216, where contracts were made during the temporary suspension of a partnership at will, it was held that the defendants were not liable to account for profits under the next succeeding section, but were liable to account for profits so far as they were made by the use of partnership property. A partner making use of information which he has obtained in the course of the partnership business must account to the partnership, Aas v. Benham, [1891] 2 Ch. 244. See also 36 English and Empire Digest (Rpl.) p. 527; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 525. 33. Duty of partner not to compete with firm. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 30. If a partner, without the consent of the other partners, carries on any business of the same nature as and competing with that of the firm, he must account for and pay over to the firm all profits made by him in that business. A partner engaging in a business which is not of the same nature need not account for the profits even though he has covenanted not to carryon any business, Dean v. MacDowell (1878), 8 Ch. D. 345. See also Fleming v. McKechnie (1905), 25 N.Z.L.R. 216; 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.) pp. 528, 529; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 525. 34. Rights of assignee of share in partnership. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 31. (1) An assignment by any partner of his share in the partnership, either absolute or by way of mortgage or redeemable charge, does not, as against the other partners, entitle the assignee, during the continuance of the partnership, to interfere in the management or administration of the partnership business or affairs, or to require any accounts of the partnership transactions, or to inspect the partnership books, but entitles the assignee only to receive the share of profits to which the assigning partner would otherwise be entitled, and the assignee must, except in case of fraud, accept the account of profits agreed to by the partners. (2) In case of a dissolution of the partnership, whether as respects all the partners or as respects the assigning partner, the assignee is entitled to receive the share of the partnership assets to which the assigning partner is entitled as between himself and the other partners, and, for the purpose of ascertaining that share, to an account as from the date of the dissolution. As to introduction of new p-Irtners, see s. 27 (7). 430 PARTNERSHIP Vol. 13 With respect to what amounts to an assignment of an interest in a partnership, see Collins v. Collins, [1911] St. R. Qd. 241; [1911] Q.W.N. 53 (letter to solicitors of partner,hip notif}ing them of desire to make immediate transfer held an equitable assignment); Anning v. Anning (1907),4 C.L.R. 1049 (interest assigned by voluntary deed); Gander v. Murray (1907), 5 C.L.R. 575 (sale of authority to prospect for minerals). An assignee of a share in a partnership, to whom this section applies, is not liable under a guarantee given by the partnership subsequently to his assignment, Hocking v. Western Australian Bank (1909), 9 C.L.R. 738. See also 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.) pp. 548, 568; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 535. DISSOLUTION OF PARTNERSHIP AND ITS CONSEQUENCES 35. Dissolution by expiration or notice. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 32. Subject to any agreement between the partners, a partnership is dissolved( 1) If entered into for a fixed term, by the expiration of that term; (2) If entered into for a single adventure or undertaking, by the termination of that adventure or undertaking; (3) If entered into for an undefined time, by any partner giving notice to the other or others of his intention to dissolve the partnership. In the last-mentioned case the partnership is dissolved as from the date mentioned in the notice as the date of dissolution, or, if no date is so mentioned, as from the date of the communication of the notice. As to the effect of continuance beyond a fixed term, see s. 30. Where the original project of a partnership had been abandoned and business was carried on partly for other purposes, it was held that the partnership was one for an undefined time and, therefore, determinable by notice, Kelly v. Tucker (1907), 5 C.L.R. 1. A partnership to continue so long as profitable is nat merely a partnership at will, but for a period which, though uncertain at its commencement and such possibly as might only terminate with the life of one partner, is not an undefined time within the section, WilSall v. Kirkcaldie (1894), 13 N.Z.L.R. 286. See also Pizi/li,ps v. Melville, [1921] N.Z.L.R. 571. With paragraph (3), cf. s. 29. Dissolution is not effected till notice is received by the partners; so where a partner dies after giving notice, but before its receipt, the partnership is dissolved by death, s. 36 (I); Mcuod v. Dowling (1927),43 T.L.R. 655. For the lights of an outgoing partner where business is carried on without settlement of accounts, see s. 45. As to liability of retiring members, see s. 39. See 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 562. 36. Dissolution by insolvency, death, or charge. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 33. ( 1) Subject to any agreement between the partners, every partnership is dissolved as regards all the partners by the death or insolvency of any partner. . (2) ~ partnership may, at the option of the other partners, be dIssolved If any partner suffers his share of the partnership property to be charged under this Act for his separate debt. Dissolution results on the death of a partner though the agreement was for a term of years, Gillespie v. Hamilton (1818), 3 Madd. 251. And see the cases cited in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.) p. 608; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 563. PARTNERSHIP ACTS, 1891 TO 1965 ss.34-38 431 Bankruptcy ordinarily dates from the act of bankruptcy on which the sequestration order is made, Bankruptcy Act 1924-1965, s. 90 (Commonwealth). As to bankruptcy of partners and partnerships and proceedings in bankruptcy by partnerships, see ss. 39 (3),41, post, and Bankruptcy Act 1924-1965, ss. 5 (2), 28-34, 84 (4), 113 (Commonwealth). As to the charge referred to in subsection (2), see s. 26. For the rights of the estate of a deceased or bankrupt partner where business is carried on without settlement of accounts, see s. 45. See Re F., [1941] V.L.R. 6, distinguishing Ahmed Anguillia Bin Hadgee v. Estate and Trust Agencies (1927) Ltd., [1938] A.C. 624; [1938] 3 All E.R. 106. In Horan v. Horan and Hayward, [1955] Q.W.N. 36. where judgment by default had been obtained against a firm which prior to the action had been dissolved by the death of one of the partners, Stanley, J., holding that the judgment was enforceable against the surviving partner, refused an application by the executrix of the deceased partner to set the judgment aside and also an application to investigate the affairs of the partnership. Where a surviving partner has an option to purchase a deceased partner's interest, although no particular words be necessary for the exercise of the option, the words used must constitute an unqualified acceptance of the obligations imposed by the option clause, and in any event where no time is limited it must be exercised within a reasonable time, Ballas v. Theophilos, [1958] V.R. 576. In Rohertson v. Commissioner of Stamp Duties, [1958] Qd. R. 342, the Full COllrt held that a partnership of which the testator was a member did not continue after his death; that thereafter by agreement tacit or express a new firm was created between the surviving partners and the executors. 37. Dissolution by illegality of partnership. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 34. A partnership is in every case dissolved by the happening of any event which makes it unlawful for the business of the firm to be carried on or for the members of the firm to carry it on in partnership. See notes to s. 5, and 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.) p. 450; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., pp. 483. 564. 38. Dissolution by the court. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 35. 48 Vic. No.8, s. 136. On application by a partner the court may decree a dissolution of the partnership in any of the following cases:( 1) When a partner is shown to the satisfaction of the court to be of permanently unsound mind, in which case the application may be made as well on behalf of that partner by his committee or next friend or person having title to intervene as by any other partner; (2) When a partner, other than the partner suing, becomes in any other way permanently incapable of performing his part of the partnership contract; (3) When a partner, other than the partner suing, has been guilty of such conduct as, in the opinion of the court, regard being had to the nature of the business, is calculated to prejudicially affect the carrying on of the business; (4) When a partner, other than the partner suing, wilfully or persistently commits a breach of the partnership agreement, or otherwise so conducts himself in matters relating to the partnership business that it is not reasonably practicable for the other partner or partners to carryon the business in partnership with him; (5) When the business of the partnership can only be carried on at a loss; 432 PARTNERSHIP Vol. 13 (6) Whenever in any case circumstances have arisen which, in the opinion of the court, render it just and equitable that the partnership be dissolved. For the right of a partner ,to have a winding-up by the court where a partnership has been dissolved, see s. 42. Under the Companies Acts, 1961 to 1964, ss. 314 et seq., title COMPANIES, Vol. 2, p. 366, a partnership which consists of more than five members may be wound up as an unregistered company in the cases set out in s. 315. As to dissolution and accounts of mining partnerships, see Mining Acts, 1898 to 1967, s. 132, title MINING, p. 68, ante. The court may dissolve a limited partnership registered under s. 57 of the Mercantile Acts, 1867 to 1896, title MERCANTILE LAW, Vol. 12, p. 129, notwithstanding that the time limited for continuance of such partnership by the registered certificate has not arrived, Groves v. Mathea (1898), 9 Q.L.J. 32. Where in an action for dissolution of a partnership objection is raised on motion for the appointment of an interim receiver and manager it is incumbent on the objector, in order to disqualify the person nominated, to establish an active partiality. A mere business connexion between the proposed receiver and one of the parties is not sufficient. See ,the judgment of Wanstall, J., in King v. Griffiths, [1958] Q.W.N.22. The general rule is that costs of an action for dissolution and taking of a partnership account are to be borne by the partnership estate unless there is a good reason to order one or other party to bear 1hem, Queensland Trustees Ltd. v. Fawckner, [1964J Qd. R. 153. As to service of the writ when the respondent cannot be located, see Vardallega v. Petrinec, [1965] Q.W.N. 36. Paragraph (1 )-As to dissolution where a partner is a mentally ill person, see also Mental Health Acts, 1962 to 1964, s. 46; Third Schedule, clause 25, ,titie MENTAL HEALTH, Vo!. 11, pp. 746, 769. Where the Public Curator desires to defend an action for dissolution on behalf of a mentally ill partner, he must obtain appointment as a guardian ad litem, Alexander v. Beaumont, [1904] Q.W.N. 28. See generally, as to effect of insanity on a partnership, 33 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.) pp. 662 et seq.; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 567. Paragraph (3)-As to what misconduct is sufficient to justify di'solution, see Clifford v. Timms, [1908] A.C. 12; Carmichael v. Evans [1904] 1 Ch. 486; Snow v. Milford (11\68), 18 L.T. 142; and 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.) p. 615. See also Vardanega v. Petrinec, [1965] Q.W.N. 36. Paragraph (4 )-Dissolution will not be decreed unless the partner has substantially failed ,to perform the agreement, Wray v. Hutchinson (1834), 2 My. & K. 235. See also the cases in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.) pp. 615, 616; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 569. Paragraph (5)-There must be a practical impossibility of making a profit, and this cannot be inferred if the loss can be attributed to special circunlstances, Handyside v. Campbell (1901), 17 T.L.R. 623. Where, at the time the partnership was entered into the business could only be carried on at a loss, the partnership was dissolved and the whole pren!ium paid by the plaintiff ordered to be refunded, ]UIl'\o1l v. McMullen, [1922] N.Z.L.R. 677. See also 36 English and Empire Digest (RpJ.), pp. 616; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 570. Paragraph (6)-A retrospective dissolution may be ordered, Phillips v. Melville, [1921] N.Z.L.R. 571. Thus the court will decree a dissolution if it is impossible to carry out the terms of the partnership agreement, Baring v. Dix (1786), 1 Cox Eq. Cas. 213, or if a deadlock has ari'.en, Re Yenidje Tobacco Co. Ltd. [1916] 2 Ch. 426; [1916-7] All E.R. Rep. 1050. See also Vardanega v. Pdrillec, [1965] Q.W.N.36. 39. Rights of person dealing with firm against apparent members of firm. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 36. ( 1) Where a person deals with a firm after a change in its constitution he is entitled to treat all apparent members of the old firm as still being members of the firm until he has notice of the change. PARTNERSHIP ACTS, 1891 TO 1965 ss.38-42 433 (2) An advertisement in the Gazette shall be notice as to persons who had not dealings with the firm before the date of the dissolution or change so advertised. (3) The estate of a partner who dies or who becomes insolvent, or of a partner who, not having been known to the person dealing with the firm to be a partner, retires from the firm, is not liable for partnership debts contracted after the date of the death, insolvency, or retirement respectively. See 36 English and Empire Digest (Rp!.), p. 486; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 515. 40. Right of partners to notify dissolution. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 37. On the dissolution of a partnership or retirement of a partner any partner may publicly notify the same, and may require the other partner or partners to concur for that purpose in all necessary or proper acts, if any, which cannot be done without his or their concurrence. The court will compel a partner to concur in the issue of a notice of dissolution, Troughton v. Hunter (1854),18 Beav. 470; Hendry Y. Turner (1886), 32 Ch. D. 355. 41. Continuing authority of partners for purposes of winding up. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 38. After the dissolution of a partnership the authority of each partner to bind the firm, and the other rights and obligations of the partners, continue notwithstanding the dissolution so far as may be necessary to wind up the affairs of the partnership, and to complete transactions begun but unfinished at the time of the dissolution, but not otherwise: Provided that the firm is in no case bound by the acts of a partner who has become insolvent; but this proviso does not affect the liability of any person who has after the insolvency represented himself or knowingly suffered himself to be represented as a partner of the insolvent. Dissolution does not affect the duty of each partner to perform a contract with strangers which has still to be completed on the part of the firm, and the firm continues to exist for .the purposes of such contract, Davis v. Firman (1902), 28 V.L.R. 53. The other party is also bound to complete, and merely continuing to carry out the terms of a contract after the dissolution does not of itself create a new contract with the continuing members of the firm, ibid. A continuing partner is not entitled to exercise on his own behalf an option of renewal given by a contract with the original firm, ibid. Payment of a debt to any partner discharges the debt, Duff Y. East India Co. (1808), 15 Yes. 198; but a partner has no implied authority to receive payment of a debt due to his co-partner in his individual capacity, Powell Y. Brodhurst, [1901] 2 Ch. 160. The bankruptcy of a partner dissolves the partnership, s. 36. See generally 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rp!.), p. 503; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 574. 42. Rights of partners as to application of partnership property. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 39. On the dissolution of a partnership every partner is entitled, as against the other partners in the firm, and all persons claiming through them in respect of their interests as partners, to have the property of the partnership applied in payment of the debts and liabilities of the firm, and to have the surplus assets after such payment applied in payment of what may be due to ,the partners respectively after deducting what may be due from them as partners to the firm; and for that purpose any partner or his representatives mayan the termination of the partnership apply to the court to wind up the business and affairs of the firm. 434 PARTNERSHIP Vol. 13 As to partnership property, see ss. 23-25. See s. 47, as to distribution of assets. Where a partnership is dissolved on lhe ground of fraud or mispresentation, the innocent partner is entitled to a lien on the assets, s. 44. No partner has any definite share or interest in the assets collected, but merely a right to have the assets applied in discharging liabilities, and to receive a share of the surplus, Public Trustee v. Elder, [1926] Ch. 266, 776. As to an order for preservation of the partnership bu~iness and assets during dissolution proceedings, see Shanks v. Shanks, [1902] Q.W.N. 59. A partner will be appointed receiver and manager of the partnership assets and business during dissolution proceedings only in exceptional circumstances, Cook v. Cook, [1904] Q.W.N. 27. See Robertson v. Commissioner of Stamp Duties, [1958] Qd. R. 342. See also Vardanega v. Petrinec, [1965] Q.W.N. 36. See generally, as to the distribution of profits made after dissolution, and the right of the outgoing partner or his estate, the cases in 36 English and Empire Digest (RpI.), p. 624; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 575. 43. Apportionment of premium where partnership prematurely dissolved. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 40. Where one partner has paid a premium to another on entering into a partnership for a fixed term, and the partnership is dissolved before the expiration of that term otherwise than by the death of a partner, the court may order the repayment of the premium, or of such part thereof as it thinks just, having regard to the terms of the partnership contract and to the length of time during which the partnership has continued; unless ( 1) The dissolution is, in the judgment of the court, wholly or chiefly due to the misconduct of the partner who paid the premium; or (2) The partnership has been dissolved by an agreement containing no provision for a return of any part of the premium. A partnership at will is apparently not within this section. A court of appeal will not interfere with the judge's discretion except on special grounds, Lyon v. Tweddell (1881), 17 Ch. D. 529. Sec also the cases in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), p. 617 (as to the exercise of the discretion); Janson v. McMullen, [1922] N.Z.L.R. 677; Re Arbitration between Bruges and Cow, [1926] N.Z.L.R. 893; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 570. 44. Rights where partnership dissolved for fraud or misrepresentation. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 41. Where a partnership contract is rescinded on the ground of the fraud or misrepresentation of one of the parties thereto, the party entitled to rescind is, without prejudice to any other right, entitled(1) To a lien on, or right of retention of, the surplus of the partnership assets, after satisfying the partnership liabilities, for any sum of money paid by him for the purchase of a share in the partnership and for any capital contributed by him; and is (2) To stand in the place of the creditors of the firm for any payments made by him in respect of the partnership liabilities; and (3) To be indemnified by the person guilty of the fraud or making the representation against all the debts and liabilities of the firm. An action lies, also, for damages where there has been fraud; see Derry v. Peek (1889), 14 App. Cas. 337; [1886-90] All E.R. Rep. 1; Redgrave v. Hurd (1881),20 Ch. D. 1. PARTNERSHIP ACTS, 1891 TO 1965 ss.42-46 435 The defrauded partner has, also, a lien for interest on such money and costs, Mycock v. Beatson (1879), 13 Ch. D. 384. As to indemnity, see Adam v. Newbigging (1888), 13 App. Cas. 308. The contract must be repudiated within a reasonable time after discovery of the fraud; see Clough v. London and N.W. Ry. Co. (1871), L.R. 7 Ex. 26, 35, and cannot be repudiated if there has been an election not to rescind, Law v. Law, [1905] 1 Ch. 140; [1904-7] All E.R. Rep. 526. See 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 548. 45. Right of outgoing partner in certain cases to share profits made after dissolution. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 42. (1) Where any member of a firm has died or otherwise ceased to be a partner, and the surviving or continuing partners carry on the business of the firm with its capital or assets without any final settlement of accounts as between the firm and the outgoing partner or his estate, then, in the absence of any agreement to the contrary, the outgoing partner or his estate is entitled at the option of himself or his representatives to such share of the profits made since the dissolution as the court may find to be attributable to the use of his share of the partnership assets, or to interest at the rate of five per cent. per annum on the amount of his share of the partnership assets: (2) Provided that where by the partnership contract an option is given to surviving or continuing partners to purchase the interest of a deceased or outgoing partner, and that option is duly exercised, the estate of the deceased partner, or the outgoing partner or his estate, as the case may be, is not entitled to any further or other share of profits; but if any partner assuming to act in exercise of the option does not in all material respects comply with the terms thereof, he is liable to account under the foregoing provisions of this section. This section has no application to a partnership business carried on by the surviving partner only for the purpose of winding it up, Powell v. Powell (1932), 32 S.R.(N.S.w.) 407. For the principles on which accounts should be taken in the case of an abortive purchase by the surviving partner, see De Renzy v. De Renzy, [1924] N .Z.L.R. 1065. In taking an account an allowance will be made to the surviving partner for managing the business, Yates v. Finn (1880), 13 Ch. D. 839. As to agreements excluding the right to profits, see the leading case of Vyse v. Foster (1874), L.R. 7 H.L. 318. As to whether profits accruing prior to the date of death of a deceased partner are to be treated as capital or income for the purposes of distribution of his estate, see Hughes v. Fripp (1922), 30 C.L.R. 508. See generally the cases collected in 36 English and Empire Digest, (Rpl.), p. 624; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 537. 46. Retiring or deceased partner's share to be a debt. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 43. SUbject to any agreement between the partners, the amount due from surviving or continuing partners to an outgoing partner or the representatives of a deceased partner in respect of the outgoing or deceased partner's share is a debt accruing at the date of the dissolution or death. . See Neylan v. Bain, [1956] St. R. Qd. 39, where the Full Court, applying Winson v. John I. Thornycroft & Co. Ltd., [1940] 2 K.B. 658, and Re Bradbury, [1943] Ch. 35, held that the property of the partnership at the date of dissolution included a contingent right to commission. See also Robertson v. Commissioner of Stamp Duties, [1958] Qd. R. 342. 436 PARTNERSHIP Vol. 13 47. Rule for distribution of assets on final settlement of accounts. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 44. In settling accounts between the partners after a dissolution of partnership, the following rules shall, subject to any agreement, be observed:(1) Losses, including losses and deficiencies of capital, shall be paid first out of profits, next out of capital, and lastly, if necessary, by the partners individually in the proportion in which they were entitled to share profits. (2) The assets of the firm including the sums, if any, contributed by the partners to make up losses or deficiencies of capital, shall be applied in the following manner and order:(a) In paying the debts and liabilities of the firm to persons who are not partners therein; (b) In paying to each partner rateably what is due from the firm to him for advances as distinguished from capital; (c) In paying to each partner rateably what is due from the firm to him in respect of capital; (d) Tb.e ultimate residue, if any, shall be divided among the partners in the proportion in which profits are divisible. As to the proportion in which partners are entitled to share profits, see s. 27 (1). With respect of bankrupt estates, see Bankruptcy Act 1924-1965, s. 84 (4) (Commonwealth). See generally, 36 English and Empire Digest (Rp!.), p. 628; 28 Halsbury's Laws of England, 3rd ed., p. 579. For the jurisdiction of Magistrates Courts in actions to recover the unliquidated balance of a partnership account, see Magistrates Courts Acts, 1921 to 1964, s. 4 (1) (b), title MAGISTRATES COURTS, Vol. 11, p. 29. For similar jurisdiction of District Courts, to the extent of $3,000, see District Courts Act of 1967, s. 67, 1967 Annual Volume. In Miles v. Clarke, [1953] 1 AI! E.R. 779, where there had been no agreement except as to the division of profits, it was held that, with the exception of the consumable stock actually used in the business. which should be treated as a partnership asset notwithstanding that it had all been brought in by one partner. all the other assets (including lease of premises. equipment and personal goodwill) should be treated as being the property of the partner who brought them in. SAVING 48. Saving of rules of equity and common law. 53 & 54 Vic. c. 39, s. 46. The rules of equity and of common law applicable to partnership shall continue in force except so far as they are inconsistent with the express provisions of this Act. This Act is declaratory only, British Homes Assurance Corpn. v. Paterson, [1902] 2 Ch. 404, at p. 410. In Dyer v. Samman, [1956] V.L.R. 49; [1956J A.L.R. 307, where the plaintiff claimed a declaration of dissolution of partnership. accounts and enquiries, the appointment of a receiver and such further and other relief as the court should deem fit. Hudson, J., in granting an account of partnership from the commencement thereof to the date when the defendant's notice of dissolution had become effective, dealt with a contention of the defendant that an allowance should be made against the plaintiff, who, in hreach of a term of the agreement, which was under seal and required him to devote the whole of his time to the business. caused loss to the pZlrtnership. His Honour, being satisfied that the loss of profits so caused was substantial, ordered an enquiry by the Master, in the taking of the accounts, as to the sum to be debited against the partner in default by reason of such breach. SCHEDULE [Repealed. See note to s. 4, ante.]