OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ

advertisement

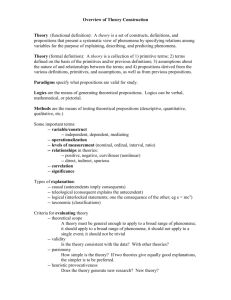

OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ On Theory Construction and Verif cation Masayuki Miki I . lntr oduction In recent years, there have been many disputes over the methodology of theory construction among accounting scholars The last fifteen years of accounting history seem to be remarkable in particular and seem to be part of a transition period replacing the inductive or descriptive approach of traditional accounting with the deductive or normative approach. It is often said that traditional accounting theory has been constructed as a distillation of experience and developed as a tool which assigns current practices to much reliability. Therefore, traditional accounting theory has been considered to be not a "science", but only an "art" a s to how we compute enterprise income. Even if someone said that traditional accounting the01y is a scientific theor y, another one criticized that it is no more than an infant of science Although we don't think simply that traditional accounting theory is only a tool of current practices or an "art" as opposed to a "science", we must listen straightforwardly to such criticism and build more desirable basic theory than before This basic theory of accounting ought to be built on the basis of scien. tific methodology The first step in pursuit of the basic theory is to elucidate the nature and subject matter of accounting theory as an empirical theory. On looking a t the recent literature of accounting from such a point of view, Professor This paper was written for presentation to the joint seminar of Professor Robert R . Sterling and Assistant Professor L T. Johnson while I was working a s a Visiting Research Associate a t Jesse H Jones Graduate School of Administration, William Marsh Rice University (Houston, Texas), from 1975 to 1977 . OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ Robert R Ster ling's ax ticle, "On theory constxuction and vex if ication" appears t o be one of the most ambitious and valuable pieces of literature The purpose of this paper is to clarify the nature and subject matter of accounting theory as an empirical theory through a critical examination of Sterling's article. I1 The Examination of Sterling's Article His a1ticle consists of the following four parts: 1) Introduction, 2) The nature of theories, 3) Some accounting interpretations, 4) A program for constructing a theory of relevant measurements. In the Introduction, he points out that "although the process of theory const. ruction is imperfectly understood, it has been noted that the theories of empirical science have some common properties and that they share a structuue." And, he starts reviewing "the nature of empirical theories for the purpose of providing a relief for some current and proposed theories of accounting." Then, some alternative interpretations of accounting are examined critically, and finally an over view for a program for the construction of a theory of relevant measurements is suggested. We will examine them in due order i ) The nature of theories. His explanation of theories may be summarized as follows: A "theory" is a set of sentences Theories are expressed in a language. Therefore, i t is pertinent to make reference to the study of language for the study of theories There are three areas in the study of language. First, syntactics is the study of logical relations of signs to signs syntactical propositions-such positions-are propositions are often said to be analytical pro- true, comes into question in syntactics. have no empirical content Whether or not Syntactical propositions The relation of signs to signs becomes true by virtue of a set of syntactical rules or definitions For example, a mathematical pro- OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ On Theory Construction and Verification 335 position, (a+ b ) 2 = a 2 f2 a b f b2, is analytical Second, semantics is the study of interrelation of signs t o referents in the real world. We need semantical rules to link between a particular sign and a particular referent. BY virtue of such semantical rules, semantical propositions are given empirical meaning to abstract signs. contents are called empirical propositions The propositions with empirical An empirical proposition is referred to as something in the real world, while an analytical proposition says nothing about it. Therefore, the true value [of empirical propositions is verified by operation of obser vations . Third, pragmatics is the study of behavioral relation of signs to the users of those signs. Different signs invoke different responses from a particular user even though those signs are intended to have the same referent. These three divisions of the study of language provide the basis for two divisions-empir ical and nonempir ical-of sciences. As the ptopositions of nonempirical sciences are logically proved by the syntactical rule, they don't depend upon empirical findings for their truth value. On the other hand, the empirical sciences have for their purpose the explanation and prediction of occurrences in the real world. The propositions of empirical sciences, therefore, are said to be true only if they correctly explain or predict some empirical phenomena The structure of a theory of such empirical science may be divided into two parts as follows: (1) A Formal or Axiomatic System which is composed of abstract symbols and a set of syntactical rules for manipulating those symbols. (2) An Interpretation of the formal system which connects certain symbols to observations via semantical rules The former is a syntactical or logical part which can be abstracted and studied in isolation for an empirical part of that theory, but the formal system per se is not an empirical theory In order for the formal system to function as a theory of empirical science, it is indispensable that we add an intetpretated part of the formal system which gives empirical meanings to certain symbols. As the propositions of the inter pr etated part are intended to be empirical, they must OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ be tested by observations. But this does not entirely imply that all propositions of an empirical theory must be verified by observations There are many terms which operate within the formal system that do not depend on observations. However , an empirical theory must have some propositions that are verifiable . After the empirical Input to a for ma1 system is manipulated by syntactical rules, the Output from the formal system is connected via semantical rules to observations. If the observations are a s specified by the formal system, then the particular proposition is said to be verified propositions is taken as a test of theory . The verification of these individual If the propositions are found to be true, then the theory is said to be confirmed. The part of his ax ticle on "The Nature of Theories" is intended to clarify the construction process and the structure of empirical theories. This results in making clear to a certain extent that an empirical theory is composed of a Formal System and an Interpretation of the formal system and how each part of the theory plays an important par t in the empirical theory This is diagrammed a s follows: Theory Plane 1 Inputs / -' Syntactical Manipulation 1 1 Outputs 1 The view that divides an empirical theory into two such parts can be found in the literature of scientific philosophy. But such a view could not have been discovered in the accounting liter ature because accounting theory or "gener ally accepted accounting principles" have been considered to be inductively formed by summarizing accounting pr actices in the past and present Therefore, the attempt to construct deductively accounting theory by means of the method of empircal science calls for reflection, all the more, about the research idea of the current accounting theories and, also, enlightens us on many points. OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ On Theory Construction and Vex if ication 337 -123- On examining his article in detail, however, we can discover four problems. First, the process of empirical theory construction a s a deductive system is not always explained clearly Also, there is no explanation about the mechanism of dynamic development of empirical theories For example, what is input into a formal system? What is meant specifically by the suggestion that the output from the formal system can have empirical meanings by observations? How does the theory constructed develop through the mechanism of falsification? ... confirmation and and so on. Second, there is a problem with the lack of verification to the theory's proposition. It is said that an empirical theory must have some propositions which are verifiable. While this is generally true, it is also the case that some empirical theories with the lack of vex ification of propositions have their r aison d'etre as theories explaining the phenomena in the real world. For example, in the current economic theory of consumer's behavior as i t is often explained in many textbooks, consumer s optical equilibrium is attained when the consumer's substitution ration (or slope of relative marginal utilities) i s just equal to the ratio of the prices of two products. Nevertheless, it is said to be very difficult f or economists to ver ify this proposition by way of observation or experiments. But this proposition is considered to be "valid" to explain consumers' behavior. Why i s i t ? Why is the unverifiable or unverified theory worth existing? In short, we can say that the second problem is the stability and creditability of theory. Third, why does an empirical theory have the character of a deductive system? What Sterling says, after all, implies that an empirical theory must be formed by a deductive system. A deductive system forms a 'cdeductive" connection with -and some prosyntactical rules - they a small number of basic propositions - they are called "Axioms" "ositions which are derivable from Axioms by a set of are called "Theorems". In other words, the theory construction by a deductive system is to describe accounting phenomena by a formal system with formal logic. system? But, why do we have to construct accounting theory as a deductive OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ Fourth, what determines that one theory is superior to the other, if two theories exist that explain the same phenomenon? The purpose of Sterling's article, of course, is not intended to explicate comprehensively only the nature of theories.' problems. Therefore, it is natur a1 to have such But since the above problems should not be overlooked in the con- struction of accounting theory as an empirical science, ithese problems will be clarified in section 111. (ii) Some accounting interpretations Sterling follows the above review of the nature of [empirical theories with a critical examination of some methods of accounting theory developed in the past. He prefaces that examination with the point that "different theories are often theories about different subject matters and the problem is not so much that there are conflicting theories about the same subject matter a s i t i s that the various theories are concernerned with different subject matters." important point This is a very But it seeins to have been overlooked by many other theorists. a ) An Anthropological Interpretation This method is "to observe accountants' actions and then rationalize those actions by subsumming them under generalized pr inciples ." Generalized principles are formed inductively by observing a lot of individual actions, each of which is ref ex red to as the "principles of accounting ." These "principles of accounting" are usually considered to be "a theor y that says that under such and such conditions the accountant will act in such and such a way." "The result is not a theory about accounting or a theory about the things to be accounted for, but a theory about accountants." The anthropological interpretation of accounting has been applied as the explantion of accountants' action for a long time. We may call i t , so to speak, one of the most traditional approaches. But Sterling criticizes that this traditional approach errs in "concluding that because X is the case, then X ought to be " And also, he says "this kind of theorizing may provide us with an explanation of why accountants act in a certain way, and it may provide us with the ability to predict their action, but it does OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ On Theory Construction and Verification 339 -125- not yield a judgement about the goodness of their action." We can not conclude, to be sure, that because an accounting man acts in fact in a certain way, then he ought to act in such manner. ought to be What is may be quite different from what But shouldn't we consider that Sterling attempts to build accounting theor y on the basis of the common proper ties of empirical sciences? If he tries to do so, there can be no justification for criticizing another theory on the ground that an anthropological interpretation doesn't produce any judgement about the goodness of actions. Also, Ste~lingsays "that the theory of accounting ought to be concerned with accounting phenomena, not practicing accountants, in the same way that theories of physics are concerned with physical phenomena, not practicing physicists." But accounting phenomena are, in nature, "social" phenomena which are based on the behavior of human beings, in the same way that economic phenomena are based on the behavior of human beings who take part in economic activity. "Social" accounting phenomena are quite different from natur a1 phenomena in that they are the phenomena of human beings with their "purpose" or with their "intention " posive." 'The phenomena we label "social" imply almost invariably "pur- One of the primary objectives of social sciences is to explain system- atically the purposive behavior and institutions of human beings. I t may be taken into account that social phenomena occur for a certain "purpose." The natural phenomena, such as atoms, gravity, friction, rays, don't occur for a certain purpose. Thus, the objective of accounting theory is mainly to explain the social behavior of accountants and economic and legal institutions surrounding what is called "accounting." Although accounting phenomena are not rest1 icted to only the behavior of accountants, it forms one of the most important parts of accounting. Therefore, the theory of accounting ought to be concerned with accounting phenomena including practicing accountants. In short, I can not agree to the following points of Sterling's view : 1) He asserts that an anthropological interpretation does not yield a judgement about the goodness of actions, in spite of the fact that he presupposes that OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ the empirical sciences have for their purpose the explanation and pr ediction of occurrences in the real world He asserts that the theory of accounting should not be concerned with 2) practicing accountants. But, the actions of accountants are generally con- sidered to be one of the main factors of accounting phenomena b) A Model-of-the-Fir m Interpretation Under this interpretation, "the accounting system is taken as a model of the firm in much the same way that a planetarium is a model of the sky ." Trans- actions' activity is inputs to the accounting system which is a formal system. Once the transaction is the input to the formal system, it i s manipulated by certain syntactical rules. Then, it turns into outputs such a s the financial statements or the balance of any particular account. The outputs are ver ified by auditing The a ~ ~ d i t i nofg the outputs means the verification of the individual proposition and the confirmation of the theory . Stel ling criticizes this interpretation from the peculiar nature of the vex ifi- ' cation process in auditing. That is, the auditing process of the outputs is not separately verified, but it is only a recalculation of the outputs and an examination of the business document in order to check on the accuracy of the inputs. For example, neither "net income" nor "total assets" are observable or separately measur eable . There are many diff ex ent accounting procedures for the allocation of cost a t this time. But, in the absence of the verification, even if there were two different accounting procedures concerned with the same phenomena and with their application resulting in contradictory outputs, the auditor will certify that both outputs are correct. In sum, Sterling views the mode!-of-the-firm interpretation a s inappropr iate because it lacks in the process of the verification. His criticism for the model-of-the-f ir m interpretation, in judging from the nature of current auditing, is vex y poignant and scathing. Of course, what does it refer to is quite right. At the present time, the auditing gives an opinion as to whether or not the financial statement actually portrays the financial position and the results of operations of the firm under examination. An auditor is not OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ 341 On Theory Construction and Vex ification -127- to "verify" the f inanciai statements and supporting accounting records of a firm , but to examine them critically and to give an opinion in the position of a professional accountant It is certainly only a recalculation of outputs within the framework of an accounting system None of the outputs of an accounting system may be concluded to be separately verified Apart from the criticism of the model-of -the-firm interpretation in the light of the nature of auditing, I will raise a question about the relation of an accounting system to a formal system. It is understood in the context of the model-of-the-firm that a formal system is an accounting system and by the verification of the outputs of an accounting system, accounting theor y can be confirmed. But a formal system per se is, as has been noted in an earlier paragraph, one of the main parts of theory On the other hand, the accounting system is the mechanism peculiar to accounting, with respect to classifying, recording, calculating and summarizing ail the transactions and reporting the results to the users. The accounting system is nothing but an object in the study of accounting theory. (Even though the accouting system is interpreted a s a "model" of the firm, a doubt is left whether the accounting system is one component of accounting theory or an object of accounting theory .) Thus, while the verification of the outputs of the accounting system does support the justification of the accounting system, it does not imply the confirmation of the accounting theory. In my view, the accounting system is the phenomenon itself in the real world and the accounting theory is a model explaining them while a model i s surrogate The phenomenon is principal A clear distinction between an accounting system and an accounting theory should be naturally drawn in the interpretation. Also, the same is true with the verification of the financial statements and the accounting theory. Each of them is quite different from each other model-of -the-f ir m interpretation, these seem to be confused However, in the Even if a "for ma1 system" were employed in a sense of a logical system peculiar to double-entry bookkeeping, it should be distinguished from a formal system in empirical the01y . OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ c) A Psychological Interpretation Under this psychological intepretation, final outputs of the model-of-the firm interpretation are broadened to include the receivers of the accounting I epor ts . The financial statements are, as indicated in the diagram below, an input to the receivers 1 I Transactions manipulation (Input) (Output) "The interpretation is identical with the above model-of-the-f ir m interpretation except for the verification of the outpts." The subject matter of the psycholgical interpretation i s concerned with how the receivers react to the financial statements The financial statements are a stimulus and the decision of the re. ceiver s is a response "If the receivers react, it is taken a s evidence that the financial statements are 'useful' or that they contain 'information'." As the r e - action of receivers is the final output of the system, the usefulnss of the financial statements is dete~minedby testing the reaction of people. Also, the test is regarded as the vex if ication of theory. The psychological interpretation is equivalent to pragmatics in the study of language. Sterling's review in regar d to this interpretation can be summarized in the following four points : 1) The psychological interpretation follows the methodology of the stimulus- response school of psychology. This results in a theory which will explain or predict the reactions of people to stimulus. But it i s not clear that a theory of accounting should take on this character. 2) The response of receivers to the financial statements does not necessarily provide justification for the usefulness of the financial statements. influence of a conditioned response must not be overlooked. The The receivers are conditioned by the conventional disclosure of financial reports. 3) The receivers may react to misinformation because there is vital distinction OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ On Theory Construction and Verification 343 -129- between pragmatic informational content and semantic infor mational content. The fact that receivers I eact to accounting repor ts does not necessarily mean that they ought to react. 4) The reaction of receivers should be taken a s the observable inputs of accounting theory. We should not take a stand on describing how the re. ceiver s react to the stimulus. The accounting theory construction by the psychological interpretation i s focused on how people I eact to accounting information. All accounting inf or ma tion is represented by signs which affect the behavio~ of people. Thus, the psychological theory constr uction amounts to the behavior a1 research of the relation of signs to the users of the accounting infor mation. cation function of accounting, From the communi- I will consider that the field of the reserch and the psychological methodology axe also very important for the study of accounting. But this field of the reseax ch has been long over looked in traditional accounting. It i s only recently since accounting theorists began to recognize the importance of the further study. We will have to expect the prospects of the findings in the future. Therefor e, we should not r un it down sweepingly. I t seems obviously to be "scientific" to explain or predict the reaction of receivers to stimulus. Stering's criticism for the psychological interpretation seems to be appropiate on the whole. In particular , the second and the third are quite pertinent. But, what he says in the fourth criticism is very doubtful to constuct "the theory of accounting" in a sense of the property of accounting theory. The matters on this point will be taken up in the following section. (iii) The methodology of Sterling's accounting theory construction and some problems After Sterling examines some alternative methodologies, he suggests an outline for a program for the construction of his accounting theory, His view of accounting is, in essence, that accounting ought to be a measurement-communication process That is, he suggests that accounting is recognized as a mechanism OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ which accountants measure something and then communicate that measurement to the people who make decisions This suggestion is not novel; it accepts the most fundamental view of accounting. But this basic point of view seems to have influence, more or less, on the characteristics of his accounting theory. When we suppose accounting is a process of measurement-communication, what should be measured? Is it the information which is relevant to the needs of decision makers? Sterling says: "If the1e exists a well-defined decision theor y, then that theory will specify what observations are to be made or what properties are to be measured " Apparently, the objects of measurement have various proper ties They have physical proper ties (color, intensity, etc ) as well a s financial properties (market value, original cost, etc.). Therefore, it may be valuable to measure all these properties But not only is it impossible for accountants to measure all properties, it is also the case that not all proper ties are useful for decision makers More importantly , a gr eat deal of various decision-making is produced by many different decision-making models Some decision makers don't know what kind of data they need to make decisions in that problematic situation. They often make erroneous decisions by a large number of erroneous decision theories. Thus, Sterling insists that what accountants ought to measure must be determined by whether or not it is relevant to that problematic situation Re- levance refers not to the needs of decision makers, but to a par ticular situation The problematic situation itself, however, does not specify the relevant data. That is why decision theory is required Also, he emphasizes that accounting concepts and figures must meet the indispensable requirement of being specified by some theory; theor y construction and measurement development are inseparable The important conclusion to be drawn from Sterling's assertion presented above is that what one ought to measure is the data specified by decision theories rather than the data desired by decision makers He attempts to introduce the findings of decision theory to the construction of accounting theory A well-de- fined decision theor y, if any, is considered a postulate or an axiom for the construction of accounting theor y. OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ On Theory Construction and Vex ification 345 -131- In Sterling's view, the objects of accounting measur ement will be restricted to meeting the I equir ement of being specified by confirmed decision theor ies . In other words, the connotation of accounting theory is prescribed by the decision theory. Therefore, there is no need to verify the theory of accounting which is being constructed. Instead, "under this view, it is the decision theories that need confirmation." If accounting is supposed to be a process of measurement- communication, the theory which is being constracted should result in only a part of the more gener a1 decision theories, not "the theory of accounting". We have described Sterling's methodology of theor y construction so f a r , Although his point of view is very tentative and suggestive, there seem to be some surprisingly important problems. those problems Next, this paper will focus on some of . One of the most important problems is as follows. He started to examine some proper ties of empirical sciences for the pur pose of giving a relief to the current accounting theory, on the premise that the subject matter of empirical theories is the explanation and prediction of occurrences in the world. In other words, the accounting theory ought to be constructed as the empirical theory which has for the subject matter the explanation and the prediction of accounting phenomena. But the accounting theory which ought to be constructed, to our surprise, abandons the verification of the theory for itself unjustifiable. This is obviously Take an example. Suppose there is a plate on a table. In this case, the role of empirical theories is to explain what the plate is made of and how it i s on the table, or to predict by how much pressure it is destroyed. The sentences of the explanation and prediction regarding the plate on the table will be induced by its observation. A set of sentences which is formed by this procedure can be confirmed through the experiment of the same observer or another whether or not they are justifiable. If a set of sentences is testified and verified by a person of reasonable qualifications under a given condition, then we can say that a set of sentences was confirmed under such condition. Thus, a set of sentences which we checked up with facts will be a set of des- OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ cr iptive, explanatory sentences. If we abandon the confirmation, even though verified propositions were introduced into a part of sentences, we can not justify the whole of the explanatory sentences. Under Sterling's view, any verification or confirmation is not attempted within the fr amewbrk of accounting theory. This implies that the theory which he tries to construct i s not accounting theory but another theory. Nothing is better evidence of another theory than the fact that he says "accounting theory is only a part of the more general decision theories." But this i s contradictory to the starting point where he tries to con. struct accounting theory a s an empirical theory. Sterling seems to abandon all possibilities of verification in the context of accounting theory. But I think it is a logical leap to abandon all possibilities. Second, an empirical theory is neither to explain that a plate ought to be made of something, nor to describe how and what ought to be dished into the plate on the table If an empirical theory i s to explain or describe what we ought to dish into the plate, it will be contradictory to the position that empirical theories have for their subject matter explanation and prediction in the real world. What ought to be dished into the plate i s an issue separated f I om empirical theories . Sterling's view seems to have the methodological characteristics of asking what ought to be dished into the plate. This metho. dology will not be in the form of an explanatory sentence which explains and describes what is, but in the form of a normative sentence which leads to a certain direction under a certain value judgement. For example, the following quotations may be taken a s good evidence of normative theor y . "It appears that much of the previous accounting literature has not been concerned with that problem (of the discovery of the relevant properties). Instead, it has been concerned with how one measures, and what one measures has been taken a s a given. My concern i s with the discovery of what one ought to measure, i. e , what properties are relevant. After that has been established, then the question of how one goes about the measurement activity should be considered." As noted in an earlier part, Sterling denies an anthropological interpretation. OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ On Theory Construction and Verification 347 -133- This is mainly because it errs in inducing what ought to be from what is, and it does not provide any norm about accounting actions. Certainly, what i s i s not what ought to be. This i s quite true, but only on that point. Why does he deny the anthropological interpretation on the ground that it does not provide a normative judgement about accounting actions? Doesn't he attempt to construct accounting theory as an empirical science which has for its subject matter explanation and prediction? Why is he not satisfied with only the explantion and prediction? The clue to the answers of those questions will be given by consider ing that he assumes implicitly as follows: Accounting theory ought to provide a certain norm about the actions of accountants as well a s explanation and pre. diction Unless it is understood that he seeks to construct the accounting theory which gives us a certain norm, his criticism against the anthropological interpretation will be full of contradictions (The theory which guides our actions t o a certain desirable direction will be called "normative theory ") It must be concIuded that Sterling's methodology takes on the character of normative theory Normative theory is quite different from descriptive theory in the point of subject matters and the methodology of theorizing. Descriptive theory is to explain facts as they are and to predict how they will be There- fore, we cannot expect descriptive theory to guide accounting practices. (These points will be discussed in section IV) . If Sterling's theory is no~mativetheory- one side of theorizing - he will be able to criticize descriptive theory - another side of theorizing. In fact, his criticism against an anthropological interpretation was, a s far as his theory is understood as normative theory, very poignant and scathing. 111. The Structure of Empirical Theories and the Process for Their Development Generally speaking, a body of systematic knowledge is required to explain and predict phenomena in the real world. I t i s certain and lawlike knowledge a s opposed to the vagueness of fragmentary knowledge. But for cet tain knowledge, , OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ it would be impossible to acceptably explain and predict phenomena in the real world. This certain knowledge is generally said to be a "theory ." The theory consists of a set of the written statements and parts of statements, which may be referred to conveniently as "formations." But this for mation of theory as described here does not imply for mation like typologies, definitional or classificational schemata. Perhaps a better definition would be that a theory is a systematically related set of statements, including some lawlike generalizations, that i s empirically testable. To constuct a theory in this sense, we will need knowledge in the sense of a hypothesis. Knowledge as a hypothesis is r epresented by a statement or a set of statements. Therefore, a scientific "hypothesis" and a "theory" are often employed a s synonyms. How a hypothesis i s acquired depends upon the various situations of scientific inquiries. But a hypothesis is generally invented by the following inferences : 1) Inductive inf ex ence , 2) Deductive inference, 3) Intuition, 4) Analogical inference, 5) Multi-dimensional inference, i , e . , the combination of those inferences. Here, the word "hypothesis" will be used to refer to whatever statement is under examination no matter whether it purports to describe some particular fact or event or to express a general law or some other, more complex, proposition. A hypothesis is required to give direction to a scientific investigation. Without such hypotheses, any scientific inquiry is blind. Scientific knowledge i s arrived a t by appiying what is often called "the method of hypothesis", i . e . , by inventing hypotheses as tentative answers to a problem under study, and then subjecting these to empirical test. But a s a hypothesis itself is not a specific proposition, we are not able to vex ify directly the hypothesis itself. So, virtually testable knowledge is inferred logically and deduced from the abstract hypothesis. To get this kind of knowledge, we have only to infer logically. The propositions which are deduced by logical inference are called "testable pr opositions" or OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ On Theory Construction and Verification 349 "observable propositions." (Car 1 G . Hempel -135- uses the word "test implications", but I think the terms "testable propositions" or "observable pr opositions" are Testable propositions are normally of a conditional easier to under stand. ) character : they tell us that under specified conditions an outcome of a certain kind will occur In other words, testable propositions can put into the explicitly conditional form that if conditions of kind '"2' are realized, then an event of kind "E" will occur. Testable propositions of this kind provide a basis for an experimental test, which amounts to bringing about the conditions "C" and checking whether " E occurs as implied by the hypothesis. A statement or set of statements is not testable a t least in principle, or if it has no testable propositions, then it cannot be significantly proposed or entertained a s a scientific hypothesis or theory, for no conceivable empirical findings can then accord or conflict with it In accordance with the direction of this testable proposition, we observe the object under study and perf or m experiments The propositions which I epr esent the results of observations and experiments are called "I epor ted propositions" . If a reported proposition "R," coincides with a testable proposition "TI", (that is, if conditions of kind "C" are given, then an event " E always occurs), we can say that the reported proposition "R," verified the testable proposition "TI". In the same way, we can infer or deduce from the hypothesis "HI" the testable ..., and we can observe and experiment in accordance with the di~ectionsof these propositions. The reported propositions R2, R3, R4, propositions T2, Tar T4. .. .., which are acquired by the observation and experiment, are checked up with the testable propositions Tz, Ts, T1" . . If each reported proposition can be taken a s good evidence oi each testable proposition, as far a s these particular propositions are concerned, we can say that the hypothesis "HI" was confirmed. A f avor able outcome of even a very extensive and exasting test can provide more or less strong evidential support or confirmation, although'it cannot provide conclusive proof for a hypothesis. The confirmation of a hypothesis will depend upon the quality and quantity oi evidence. That is, the confirmation of a OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ hypothesis depends upon the variety of evidence, as well as the quantity of the favor able evidence available. the resulting support. In gener al, the greater the variety , the stronger Thus, the creditability and stability of a hypothesis can be enhanced by the support of a great deal of various evidence. On the other hand, if the results of observations or of experiments (i. e., the reported proposition "R,") did not coincide with the requirement of the testable proposition "TI", the fact implies that the hypothesis "HI" was refuted by the reported proposition "R,". The refutation of a hypothesis implies the incompleteness of a hypothesis itself. hypothesis ''H? Then, we will have to form a new by giving up or modifying the old hypothesis "HI". pothesis "Hz" produces the testable propositions TI', T2/, T3/. way a s the above "TI". . . . via the same As a result of observations or of experiments, if the reported propositions R,', Rzf, R3/. Tzl, Tat.. The hy- . , we can say that .. can support the testable propositions TI1, the hypothesis "Hz" was conf irmed. If the reverse i s the case, the hypothesis is refuted. Needless to say, findings that are to dislodge a well-established theory have to be weig hty; and advelse experimental results, in par ticular , have to be repeatable. If the hypothesis was refuted in this way, then it will be abandoned or modified and will be converted into a newer hypothesis "H$'. Thus, an empirical theory keeps on developing, in a spir a1 process, toward a more universal and complete theory . Will the confirmation of a hypothesis imply that it i s true? no. The answer is That many testable propositions were vex if ied by many reported propositions does not imply that a hypothesis is true, but that i t was confirmed by some particular reported propositions. The creditability or the acceptabiIity of a hypo- thesis or a theory, strictly speaking, depends upon the relevant parts of a total scientific knowledge, including all the evidence relevant to the hypothesis and all the hypothesis and theories then accepted that have any bearing upon i t , That is, the creditability or acceptability is determined by the probability of the theory's acceptance within the level of a body of scientific knowiedge at a particular time In this sense, empirical science as a positivistic science may be ultimately OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ On Theory Construclion and Verification said to be a system of tentative hypotheses which are subjected to the restrictions of science a t a particular point in time As has been explained so f a r , the construction of a theory and i t s process of dynamic development mean that an empirical theory must be for med a s a deductive system. In order to form a theory a s a seductive system, first of all, we must prescribe a process of theory construction and vex ification deduction of testable propositions, reported propositions, i. e , an hypothesis, criterion of logical judgement on verification; all of which must be manipulated in a system of strictly defined signs. In other words, we can proceed by listing a set of pri- mitive elements (i. e , all terms that have no synonym in a language system), a set of axioms, a set of for mation rules (i. e , grammar which determines the permissible expressions of a language). an axiomatic system. "calculus". All of which, taken together By the application of these procedures, we can form a However , a calculus has no empirical meanings. for ma1 system. , deter mine It is a purely Ther efoxe, by adding semantical interpretation to an axiomatic system, it will be a deductive system. If so, why does an empirical theory take on the structure of a deductive system? The answer would be found in an accounting of scientific descriptions of phenomena in the real wor Id. The reason is that strict explanation is ensured by the theory developed as a deductive system. But I have no intention of concluding from this that all empirical theories now existing in our society are formed a s a deductive system, or that all accounting theories must be constructed as a deductive system. Because even if all of the axioms and theor ems were strictly prescribed and logical truth consequently ensured, it would be extremely difficult to give an axiomatic system some empir ical meaning and to verify it by observed facts. In particular , accounting handles many normative statements (for example, accounting ought to be fair ) or many imperative statements (for example, value a t market price under a particular condition) because accounting practices reflect, more or less, the needs of the society a t a particular time. This is why i t is difficult to accept all sorts of assertions into a deductive system. As already noted above, an hypothesis ,is OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ a statement or set of statements that are empir ically testable a t least in principle. It should be noted that we can not make any judgement a s to whether many normative or imperative statements regar ding the f airhess and ethics of accounting are true or false. It is not a matter of truth-value, but of consensus and selection. Therefore, it is impossible, rather than difficult, to accept asser tion into a strictly or purely deductive system and to construct accounting theory a s a deductive system. In considering the theory construction of accounting, the normative or imperative fields or phases of accounting should be distinguished clearly from the accounting fields which are describable as a deductive system. (This is the very important point, which will be explained further in the next section.) This paper will now focus on what determines the superiority or inferiority of theox ies. Suppose there are two theories to explain the same phenomena. Of course, these theories are assumed to be in search of the same subject matter for the reason that different subject matters yield different theories. In this case, what deter mines the superiority of one theory over another ? Does it depend upon only the degree of formalization? Of course it does not A theory is clearly required to be complete in the degree of formalization. The I elationship between an axiom and a theorem or testable proposition must be true in a formally logical sense. But, if the formalizations of the two theories are complete a s formal systems, it can be said that the superiority of theory depends upon how the theory can universally explain the wider range of universe of discourse with a fewer axilliar y hypotheses. On explaining a certain phenomenon, we usually use many axilliar y hypotheses or axilliar y assumptions. As described earlier , testable propositions are derived or inferred from the hypothesis that is to be tested. This statement, however, gives only a rough indication of the relation- ship between a hypothesis and the sentences that serve a s its testable propositions. In most cases, we use premises which axe tacitly taken for granted in the context of argument. By means of these premises, one can derive or infer testable propositions from a hypothesis. These premises are called axilliar y OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ On Theory Construction and Verification 353 -139- assumptions, which play the role of mediating between a hypothesis and a testable proposition. It should be noted that the more axilliary assumption an hypothesis has, the wider the universe of discourse is and the more complicated the axiomatic system. If we go far enough, a phenomenon (even if it i s ex- tremely complicated) will be explainable by means of the innumerable axilliar y assumptions. But such an explanation naturally lacks in the persuasive power . We cannot say such an "explanation" is not an explanation, however formally systematic it may be Therefore, I am of the opinion that fewer axilliary assumptions and a universal r ange of explanations deter mine the super ior ity of theory provided that the degree of formalization is the same level between two theories . The theory a s a deductive system describes the phenomenon in the real world by means of a few basic propositions (called axioms) and some testable propositions which are reduced by the application of inference rules, and then confirms the description by facts. univer se of discourse. The truth-value of theory is confirmed in a Although the confirmation of theory is desirable, it is difficult for us to confirm in the social context. This does not necessarily deny the r aison d'etre of the theory which has not been confirmed yet. In the case that there is no alternative theory which is more desirable (e.g, universal) than the present theory, the present theory, even if it has not been confirmed, has some functional value. IV. Descriptive Theory vs. Normative Theory In scientifically constructing the theory of accounting, one of the most important things i s to know "what is the subject matter of accounting theory being constructed". As different subject matters obviously are considered to yield different theories, to begin with, we must know under what subject matter theory construction i s attempted. Also, it is very important to know the pur- pose or function and limitation of the theory being constructed under a certain subject matter, especially, in criticizing another person's theory. OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ Now, according to the dif frence of subject matters, we will classify current accounting theories as two different categories. That is: 1) Descriptive theor y-Basic theory, 2 ) Normative theor y-Applied theory. These are quite heterogeneous theories in the sense that they have different subject matters. Heterogeneous theories should be distinguished clearly f rom each other. i) Descriptive theory The subject matter of this theory i s to analyze what is, to explain i t systematically, and to predict how it will change under a certain condition. That is, descriptive theor y i s to analyze genr ally accepted accounting principles, various kinds of accounting regulations, accountants' actions and accounting p~actices,etc. and then to explain by consistent methods; why they existed in the past and why they exist a t the present. I t is possible to consider that the empirical phenomena in the real world occur under certain covering pr inciples or laws. Descriptive theory attempts to explain without any contradictions a s a whole what is and what was. In other words, descriptive theory i s the inquiry of a certain principle or law covering the empirical phenomena. Of course, the success of consistent explanation will be helpful to the unknown state in the future, a s well a s in the past and a t the present. I t should be noted that descriptive theory has its essential feature in the explanation and prediction of its purpose, and it says nothing of what ought to be. Descriptive theory does not offer any 'judgement of goodness of what is, and the theory does not guide any desirable actions under a certain value judgement. Any judgement about goodness of actions cannot be expected in the descriptive theory what ought to be. . Essentially, descriptive theor y has no function of producing Some people might contend that descriptive theory has no usefulness because it does not yield any judgement about the goodness of actions, but I will say that this view i s wrong. Descriptive theory does not yield any norm of actions, but this doesn't mean that descriptive theory i s not useful in OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ On Theory Construction and Verification 355 clarifying unsolved problems and unknown states. -141- To systematically explain complicated phenomena under certain principles will be useful in the recognition and prediction of present unsolved problems and unknown states. portantly, to know what ought to be, we must recognize what i s More imSuch recog- nition i s the first step to be taken in constructing the theory of accounting. What is not what ought to be. But if we know the nature of what is, i. e. how i t is, we will be able to obtain the knowledge of how we ought to act. This is not the essential purpose of descriptive theory, but the utility of the theory . We will emphasize repeatedly that descriptive theory itself does not yield directly any judgement of what action ought to be taken. In this sense, descriptive theory is basic theory in the study of accounting. Now, attention will focus on the meaning of consistent or systematic explanation of an empirical phenomena. It implies that a theorist must recognize fully the structure of empirical theory and its process of development, a s described in an earlier section, and the construction of accounting theory in accordance with that principle. system. In a word, it i s to construct a theory as a deductive Theory constructed as a deductive system assures the creditability and acceptability of explanation. In this case, what is laid as axioms will depend upon how a specific theorist grasps the nature of accounting That is, what i s set a s axioms depends upon the selection of the specific theorist. ample, suppose the axiom of Mr. dete~minethe income of enterprises. For ex- A i s that the nature of accounting i s to Also, the axiom of M r . B is that the nature of accounting is the measurement and communication of information useful for decision-maker s . The different axioms result from the diff ex ence of recognition of what each person thinks of the nature of accounting. So the difference of axioms results from the difference of each subjective judgement. It i s very doubtful whether subjective judgements can be avoided in an ultimate sense of the words. But this subjectivity should be understood in the sense that subjectivity of human beings in fact-recognition is necessarily unavoidable. This subjectivity does not mean value-jndgement or ought-to-be judgement as will be OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ explained in the following section on normative theory. In short, we cannot evaluate the relative subjectivity of different axioms until we test the validity of testable propositions. The question i s whether the explanation system under the axiom is consistent as an axiomatic system and, also, whether the interpretation of the system corresponds to the facts observed by qualified observers. This process of theory construction and verification is regarded as the r equirement for acceptability of axioms. The existence of God can be developed by an axiomatic system. But however systematic it may be, unless the propositions of an axiomatic system are confirmed by empirical facts, we cannot say that the system i s a scientific explanation. Science is the domain of being able to bear repetitious testing. Descriptive theory is developed in the form of a deductive system to efficiently accomplish the subject matter, the explanations satisfy the requirement of explanatory relevance in the strongest sense; the explanatory infor mation they provide implies the explanandum sentence (the sentence describing the phenomena to be accounted for by an explanation) deductively, and thus offers logically conclusive grounds why the explanandum phenomena is to be expected. That is, scientific explanation i s attained with the help of a deductive system. Scientific explanation will broaden our knowledge and under standing by predicting and explaining phenomena that were not known when the theory was formulated ii) Normative theory Normative theory is the formulation of a series of statements developed on the premises of a specific value judgement or ought-to-be judgement. Norma- tive theory is not to explain what is and to predict what may happen in the future, but to reform or improve what is. As what is, without doubt, is not what ought to be, this t h e o ~ yaims a t a "more desirable" direction. desirable depnds upon a value judgement of a specific theorist . What is Conceptually, a value judgement is to say the goodness of objects and an ought-to-be judgement is to say what ought to be For example, if a person says "this picure OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ On Theor y Construction and Verification is beautiful," the observer makes a value judgement. Also, if a person says "the color of this picture ought to be painted with more blue," that is an oughtto-be judgement 'of the observer. A value judgement i s to assess objects and an ought-to-be judgement i s to require someone to ta!ce a certain action. As both jugements are considered to be a value judgement in a broad sense, we will have almost no significance of the clear distinction between the two. But, both judgements should be strictly distinguished from the fact recognition saying about the nature of what is. Normative theory starts from setting up the axioms which are based upon value judgements of observers. proposition is untestable. Therefore, i t should be noted that this kind of This point will be explained further. Suppose, a person advocates that accountants ought to use replacement cost rather than historical cost because replacement cost is very useful for the decision making of users. Also, another person contends that accountants ought to use exit value in place of historical cost. No one can Now, who can decide which contention i s right? Whether a person suppor t s replacement cost or not depends upon whether he thinks it i s "better" or "more desirable" than historical cost. same i s true for another person abvocating exit value obviously based upon different value judgements. Both contentions are Ther efor e, both contentions are a matter, not of which contention i s right, but of agreement. they are not testable propositions by observations. The Essentially, It might be better to say that there i s no need to verify all of the propositions in normative t h e o ~ y . Although there are not a few normative, ethical, imperative concepts-vex ity, fairness, conser vatism-in accounting theor y, these concepts are not consistent with descriptive theory. The statements including these concepts are not testable. Only if these concepts are applied to normative theory, will they func- tion effectively. While descriptive theory presupposes testability, normative theory does not This i s the essential difference between the two theories. Therefore, normative theory has no structure or process of devloprnent a s an empirical theory, a s descr ibed in the ear lier section Never theless, this point OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ does not deny the r aison d'etr e of normative theory . The function of normative theory exists in assessing the goodness of what is and in giving normative pressure for the pur pose of the improvement of the real world. The explanation of ncrmative theory, like descriptive theory, i s :done in the form of an axiomatic system to avoid logical contradictions and to sufficiently acquire the explanatory poweI . Normative theory always attempts to assimilate the findings of interdisciplinar y disciplines and for ms a desirable judgement, And on the basis of the value judgement, the logical development of explanation is per formed in an axiomatic system. Well-established normative theory will cause the ref or mation of the existing practices and convention in a broad sense, of social phenomena. This function of normative theory, without doubt, will be very useful for the solution of unsolved problems. V. Summary Through the examination of Professor Robert R. Sterling's article, I at- tempted to clarify the nature and subject matter of accounting theory a s an empirical theory . Although his "theory construction and verification" has some problems to be solved, he suggests many penetrating views for relief of the current confusion in accounting theories. Sterling applies the method of empir i- cal theory to the study of accounting and intends to systematize accounting theory by a scientific approach. That intention and the suggestions developed here should be highly valued. The theory of empirical science consists of a Formal system or Axiomatic system and an Interpretation of the system. A formal systemn i s a logical plane of the theory. On the other hand, an interpretation is an empirical plane following observations. Empir ical theory i s a systematically related set of statements, including some lawlilre gener alizations that are empirically testable. Empirical theory is constructed a s a deductive system to offer logically conclusive grounds why the phenomena axe to be expected. Through the procedure of confirmation, empirical theory is always modified and keeps on developing dynamically in a OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ On Theory Construction and Vex if ication 359 spir a1 process toward a more universal theor y. -145- The superiority or inferiority among some theories should note the logical systematization and empirical confirmation In this case, the super iority of theor y is determined by whether a specific theory has relatively mor e universal explanatory power by a few axilliar y assumptions than another theory. Mention of the term "accounting theory" should not be overlooked that there are two sorts of heterogeneous accounting theories which have different subject matters. Descriptive theory has for its subject matter the explanation and pre- diction of empirical phenomenon in the real world. nature of reality and precisely predicts i t s change. This theory describes the Descriptive theory says nothing of what ought to be, but it gives basic data in order to form a value judgement about what ought to be, by elucidating the nature of reality. The initial objective of accounting theories should be the study of this basic theor y . On the other hand, normative theory has for i t s subject matter the reformation of what i s empirically. This theory aims a t leading u s to more desirable directions under a certain value judgement. Like descr iptive theory, normative theory i s developed a s an axiomatic system. positions under normative theory are untestable. But all of the pro- Therefore, i t i s difficult to say that normative theory i s empirical theory. Nevertheless, the raison d'etre of normative theory should not be denied readily. Normative theory attempts to assimilate the findings of inter disci- plinar y disciplines and for m a desirable judgement. And on the basis of the value judgement, the logical development of explanation is performed in an axiomatic system. Even though normative theory must, a t the outset, rely on the findings of descriptive theory which elucidate existing conditions, the guideline of what ought to be will be enhanced by the aid of normative theory. This function of normative theory, also, will be useful for the solution of unsolved problems. In the study of accounting, we should clarify the subject matter of a constructed theory and set to work according to a scientifically appropriate meth- OLIVE 香川大学学術情報リポジトリ -146'- odology. References American Accounting Assocition, "Report of the Committee on Accounting Theory Construction and Verification," Supplement to The Accounting . Review, Vol XLVI (1971). Bedford, Norton M. Future of Accounting in a Changing Society. (Stipes Pub- . lishing Company, 1969). pp 67-92. Chisholm, Roderick M. Theory of Knowledge. (Prentice-Hall, Inc , 1966). pp. 56-69. Hempel, Carl G. Aspects of Scientific Explanation.. (The Free Press, 1965). pp. 173-187. . Philosophy of Natural Science. (The Free Press, 1966). pp. 19-69. Kurachi, Kanzo. "On the Methodology of Accounting Theory," in the regular publication No. 189 of the University of Meiiigakuin. pp.485-510. Rudner , Richard S. Philosophy of Social Science. (The Free PI ess, 1966). pp. 10-28, pp. 32-45. Sterling, Robert R. Theory of the Measurement of Enterprise Income. (The University Press of Kansas, 1970). PP. 351-361. . "On Theor y Construction and Ver if ication," The Accounting Review (July 1970). pp. 444-45-7. -- "Toward a Science of Accounting, " Financial Analyst Journal, September / October 1975. Von Wright, George H. Explanation and Under standing Press, 1971). pp. 83-131. (Cox nell University