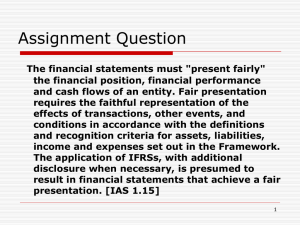

Accounting theory and conceptual frameworks

advertisement