PHYS 263 Physical Optics Lecture Notes

advertisement

PHYS261-OPTICS PART, PART 1

PHYS 263

Physical Optics

Lecture Notes

Jakob J. Stamnes

—————————————————————–

Department of Physics, University of Bergen, 5007 Bergen.

Tel: 55 58 28 18. Fax: 55 58 94 40. E-mail: JakobJ.Stamnes@fi.uib.no

Autumn 2004

Spring 2003

FYS 263

1

Contents

I

Elementary electromagnetic waves

1 Maxwell’s equations, the material

1.1 Maxwell’s equations . . . . . . .

1.2 The continuity equation . . . . .

1.3 The material equations . . . . . .

1.4 Boundary conditions . . . . . . .

3

equations,

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

and

. . .

. . .

. . .

. . .

boundary conditions

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

4

4

4

5

6

2 Poynting’s vector and the energy law

8

3 The wave equation and the speed of light

9

4 Scalar waves

4.1 Plane waves . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.2 Spherical waves . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.3 Harmonic (monochromatic) waves . . .

4.4 Complex representation . . . . . . . . .

4.5 Linearity and the superposition principle

4.6 Phase velocity and group velocity . . . .

4.7 Repetition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

11

11

12

13

14

15

15

16

5 Pulse propagation in a dispersive medium

18

6 General electromagnetic plane wave

21

7 Harmonic electromagnetic waves of arbitrary form - Time averages

24

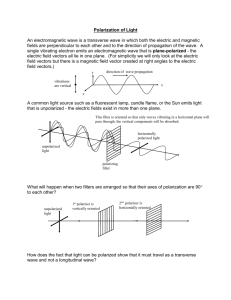

8 Harmonic electromagnetic plane wave – Polarisation

26

9 Reflection and refraction of a plane wave

9.1 Reflection law and refraction law (Snell’s law) . . . . . . . . . .

9.2 Generalisation of the reflection law and Snell’s law . . . . . . .

9.3 Reflection and refraction of plane electromagnetic waves . . . .

9.3.1 Reflectance and transmittance . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

9.3.2 Brewster’s law . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

9.3.3 Unpolarised light (natural light) . . . . . . . . . . . . .

9.3.4 Rotation of the plane of polarisation upon reflection and

9.3.5 Total reflection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . .

. . . . . .

. . . . . .

. . . . . .

. . . . . .

. . . . . .

refraction

. . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

29

29

31

32

35

38

38

39

40

FYS 263

2

List of Figures

1.1

A plane interface with unit normal n̂ separates two different dielectric media. . . . .

7

4.1

A plane wave that propagates in direction ŝ, has no variation in any plane that is

normal to ŝ. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

12

A plane wave propagates in the positive z direction in a dispersive medium that fills

the half space z ≥ 0. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

18

The vectors E, H, and ŝ for an electromagnetic plane wave represent a right-handed

Cartesian co-ordinate system. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

22

5.1

6.1

8.1

8.2

9.1

9.2

9.3

9.4

9.5

9.6

9.7

Instantaneous picture of the electric vector of a plane wave that propagates in the z

direction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The end point of the electric vector describes an ellipse that is inscribed in a rectangle

with sides 2a1 and 2a2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Reflection and refraction of a plane wave at a plane interface between two different

media. Illustration of propagation directions and angles of incidence, reflection, and

transmission. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Reflection and refraction of a plane wave. Illustration of the co-ordinate system (n̂,

b̂, t̂). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Generalisation of Snell’s law and the reflection law to include non-planar waves that

are incident upon a curved interface. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Reflection and refraction of a plane electromagnetic wave at a plane interface between

two different media. Illustration of T E and T M components of the electric field. . .

Illustration of the angle αq between the electric vector Eq and the plane of incidence

spanned by kq and êT M q . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Illustration of Brewster’s law. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Illustration of the refraction of a plane wave into an optically thinner medium, so that

θi < θt . When θi → θic , then θt → π/2, and we get total reflection. . . . . . . . . . .

27

28

29

30

32

35

36

38

41

FYS 263

3

Part I

Elementary electromagnetic waves

FYS 263

4

Chapter 1

Maxwell’s equations, the material

equations, and boundary

conditions

In this course we consider light to be electromagnetic waves of frequencies ν in the visible range, so

that ν (4 − 7.5) × 1014 Hz. Since λ = νc , where c is the speed of light in vacuum (c 3 × 108

m/s), we find that the corresponding wavelength interval is λ (0.4 − 0.75) µm. Thus, to study

the propagation of light we must consider the propagation of the electromagnetic field, which is

represented by the two vectors E and B, where E is the electric field strength and B is the magnetic

induction or the magnetic flux density. To enable us to describe the interaction of the electromagnetic

field with material objects we need three additional vector quantities, namely the current density J,

the displacement D, and the magnetic field strength H.

1.1

Maxwell’s equations

The five vectors mentioned above are linked together by Maxwell’s equations, which in Gaussian

units are

∇×H=

1

4π

Ḋ +

J,

c

c

1

∇ × E = − Ḃ.

c

In addition we have the two scalar equations

(1.1.1)

(1.1.2)

∇ · D = 4πρ,

(1.1.3)

∇ · B = 0,

(1.1.4)

where ρ is the charge density. Equation (1.1.3) can be said to define the charge density ρ. Similarly,

we can say that (1.1.4) implies that free magnetic charges do not exist.

1.2

The continuity equation

The charge density ρ and the current density J are not independent quantities. By taking the

divergence of (1.1.1) and using that ∇ · (∇ × A) = 0 for an arbitrary vector A, we find that

∇·J+

1

∇ · Ḋ = 0,

4π

FYS 263

5

which on using (1.1.3) gives

∇ · J + ρ̇ = 0.

(1.2.1)

This equation is called the continuity equation, and it expresses conservation of charge. By integrating (1.2.1) over a closed volume V with surface S, we find

∇ · Jdv = −

V

∂ρ

dv,

∂t

(1.2.2)

V

which by use of the divergence theorem gives

d

d

J · n̂da = −

ρdv = − Q.

dt

dt

S

(1.2.3)

V

Here n̂ is the unit surface normal in the direction out of the volume V , so that (1.2.3) shows that

the integrated current flux out of the closed volume V is equal to the loss of charge in the same

volume.

Digression 1: Notation

• Bold face is used to denote vector quantities, e.g.

E = Ex êx + Ey êy + Ez êz ,

where êx , êy , and êz are unit vectors along the axes in a Cartesian co-ordinate system.

• A dot above a symbol is used to denote the time derivative, e.g.

Ḃ =

∂

B.

∂t

• E, B, D, H, ρ, and J are functions of the position r and the time t, e.g.

D = D(r, t).

• The connection between Gaussian and other systems of units, e.g. MKS units, follows from

J.D. Jackson, ”Classical Electrodynamics”, Wiley (1962), pp. 611-621. For conversion between

Gaussian units and MKS units, we refer to the table on p. 621 in this book.

1.3

The material equations

Maxwell’s equations (1.1.1)-(1.1.4), which connect the fundamental quantities E, H, B, D, and J,

are not sufficient to uniquely determine the field vectors (E, B) from a given distribution of currents

and charges. In addition we need the so-called material equations, which describe how the field is

influenced by matter.

In general the material equations can be relatively complicated. But if the field is time harmonic

and the matter is isotropic and at rest, the material equations have the following simple form

Jc = σE,

(1.3.1)

D = εE,

(1.3.2)

FYS 263

6

B = µH,

(1.3.3)

where σ is the conductivity, ε is the permittivity or dielectric constant, and µ is the permeability.

Equation (1.3.1) is Ohm’s law, and Jc is the conduction current density, which arises because

the material has a non-vaninishing conductivity (σ = 0). The total current density J in (1.1.1) can

in addition consist of an externally applied current density J0 , so that

J = J0 + Jc = J0 + σE.

(1.3.4)

Digression 2: General material considerations

• A material that has a non-negligible conductivity σ is called a conductor, while a material that

has a negligible conductivity is called an insulator or a dielectric.

• Metals are good conductors.

• Glass is a dielectric; ε 2.25; σ = 0; µ = 1.

• In anisotropic media (e.g. crystals) the relation in (1.3.2) is to be replaced by D = εE, where

ε is a tensor, dyadic or matrix.

• In a plasma (1.3.1) is to be replaced by J = σE, where the conductivity is a tensor.

• There are also magnetically anisotropic media, in which (1.3.3) is to be replaced by B = µH.

Thus, in this case the permeability is a tensor. Such materials are not important in optics.

• In dispersive media ε is frequency dependent, i.e. ε = ε(ω). Maxwell’s equations and the

material equations are still valid for each frequency component or time harmonic component

of the field. For a pulse consisting of many frequency components, one must apply Fourier

analysis to solve Maxwell’s equations and the material equations separately for each time

harmonic component, and then perform an inverse Fourier transformation.

• In non-linear media there is no linear relation between D and E (equation (1.3.2) is not valid).

Most media become non-linear when the electric field strength becomes sufficiently high.

1.4

Boundary conditions

Hitherto we have assumed that ε and µ are continuous functions of the position. But in optics

we often have systems consisting of several different types of glass. At the transition between air

and glass or between two different types of glass the material parameters are discontinuous. Let us

therefore consider what happens to the electromagnetic field at the boundary between two media.

Consider two media that are separated by an interface, as illustrated in Fig. 1.1. From Maxwell’s

equations, combined with Stokes’ and Gauss’ theorems, one can derive the following boundary

conditions

n̂ · (B(2) − B(1) ) = 0,

(1.4.1)

n̂ · (D(2) − D(1) ) = 4πρs ,

(1.4.2)

n̂ × (E(2) − E(1) ) = 0,

(1.4.3)

4π

(1.4.4)

Js ,

c

where n̂ is a unit vector along the surface normal. According to (1.4.1) the normal component of

B is continuous across the boundary, while (1.4.2) says that if there exists a surface charge density

n̂ × (H(2) − H(1) ) =

FYS 263

7

^

n

ε 1, µ 1

ε 2, µ 2

Figure 1.1: A plane interface with unit normal n̂ separates two different dielectric media.

ρs at the boundary, then the normal component of D is changed by 4πρs across the boundary

between the two media. According to (1.4.3) the tangential component of E is continuous across

the boundary, while (1.4.4) implies that if there exists a surface current density Js at the boundary,

then the tangential component of H, i.e. of n̂ × H, is changed by 4π

c Js .

FYS 263

8

Chapter 2

Poynting’s vector and the energy

law

The electric energy density we and the magnetic energy density wm are defined by

we =

1

E · D,

8π

1

H · B,

8π

and the total energy density is the sum of these, i.e.

wm =

w = we + wm .

(2.1)

(2.2)

(2.3)

The energy flux of the field is represented by Poynting’s vector S, given by

c

E × H.

(2.4)

4π

Here S represents the amount of energy that per unit time crosses a unit area that is parallel with

both E and H.

In a non-conducting medium (σ = 0) we have the conservation law

S=

∂w

+ ∇ · S = 0,

∂t

(2.5)

which expresses that the change of the energy density in a small volume is equal to the energy flux

out of the same volume [cf. (1.2.2) and (1.2.3)]. In optics the Poynting vector is very important,

because its absolute value is proportional to the light intensity, i.e.

|S| ∝ light intensity.

(2.6)

The direction of the Poynting vector, defined by the unit vector

ŝ =

points in the direction of light propagation.

S

,

|S|

(2.7)

FYS 263

9

Chapter 3

The wave equation and the speed

of light

The electric and magnetic fields E and H are connected through Maxwell’s equations (1.1.1)-(1.1.4),

which are simultaneous, first-order partial differential equations. But in those parts of space where

there are no sources, so that J = 0 and ρ = 0, we can through differentiation obtain second-order

partial differential equations that E and H satisfy individually. We assume that the medium is

non-dispersive, so that D = εE, where ε̇ = 0, and B = µH, where µ̇ = 0. Then we have from (1.1.1)

and (1.1.2)

∇×H=

1

1

Ḋ = εĖ,

c

c

(3.1)

1

1

∇ × E = − Ḃ = − µḢ.

(3.2)

c

c

Next, we assume that the medium is homogeneous, so that ε and µ do not vary with position. By

taking the curl of (3.2) and combining the result with the time derivative of (3.1), we find that

1

1 1

εµ

∇ × (∇ × E) = − µ∇ × Ḣ = − µ εË = − 2 Ë.

c

c c

c

Now we use the vector relation

∇ × (∇ × A) = ∇(∇ · A) − ∇2 A,

(3.3)

(3.4)

which applies to an arbitrary vector A, to obtain

∇(∇ · E) − ∇2 E = −

εµ

Ë,

c2

(3.5)

which since ∇ · E = 0, gives

∇2 E −

εµ

Ë = 0.

c2

(3.6)

In a similar manner we find

εµ

Ḧ = 0.

c2

By comparing these results with the scalar wave equation

∇2 H −

∇2 V −

1

V̈ = 0,

v2

(3.7)

(3.8)

we see that in a source-free region of space each Cartesian component of E and H satisfies the scalar

wave equation with phase velocity

FYS 263

10

c

v=√ .

εµ

(3.9)

Note that this derivation is valid only in a non-dispersive medium in which both the permittivity

and the permeability do not depend on the frequency.

FYS 263

11

Chapter 4

Scalar waves

Scalar waves are solutions of the scalar wave equation (3.8), which is given by

∇2 V (r, t) −

4.1

1 ∂2

V (r, t) = 0.

v 2 ∂t2

(4.0.1)

Plane waves

Any solution of (4.0.1) of the form

V (r, t) = V (r · ŝ, t),

(4.1.1)

is called a plane wave, since V at any time t is constant over any plane

r · ŝ = constant,

(4.1.2)

which is normal to the unit vector ŝ (see Fig. 4.1).

To show that (4.1.1) is a solution of (4.0.1), we introduce a new variable

ζ = r · ŝ = xsx + ysy + zsz ,

(4.1.3)

so that

∂ζ

= sx ;

∂x

∂ζ

= sy ;

∂y

∂ζ

= sz .

∂z

(4.1.4)

Further we find that

∂V

∂V

∂V ∂ζ

=

·

= sx

.

∂x

∂ζ ∂x

∂ζ

2

∂2V

∂V

∂ ∂V

∂ ∂V ∂ζ

∂

2∂ V

s

=

s

=

s

=

s

=

.

x

x

x

x

∂x2

∂x

∂ζ

∂x ∂ζ

∂ζ ∂ζ ∂x

∂ζ 2

(4.1.5)

(4.1.6)

In a similar way we find

∂2V

∂2V

= s2y 2

2

∂y

∂y

;

∂2V

∂2V

= s2z 2 .

2

∂z

∂z

(4.1.7)

When we substitute (4.1.6) and (4.1.7) in (4.0.1) and take into account that s2x + s2y + s2z = 1, since

ŝ is a unit vector, the wave equation becomes

∂2V

1 ∂2V

−

= 0.

∂ζ 2

v 2 ∂t2

(4.1.8)

FYS 263

12

z

^

n

^e

r

e^ r

z

^e

φ

θ

e^ φ

^n

θ

y

^

n

^e

θ

θ

e^ θ

φ

x

Figure 4.1: A plane wave that propagates in direction ŝ, has no variation in any plane that is normal

to ŝ.

By introducing two new variables p and q, defined by

p = ζ − vt ; q = ζ + vt,

(4.1.9)

we find (Exercise 2) that the wave equation in (p, q) variables can be written

∂2V

= 0.

∂p∂q

(4.1.10)

This equation has the following general solution

V = V1 (p) + V2 (q),

(4.1.11)

where V1 and V2 are arbitrary functions. By substitution from (4.1.3) and (4.1.9) in (4.1.11), we

find the following general plane-wave solution

V (r, t) = V1 (r · ŝ − vt) + V2 (r · ŝ + vt).

(4.1.12)

ζ − vt = ζ + vτ − v(t + τ ),

(4.1.13)

V1 (ζ, t) = V1 (ζ + vτ, t + τ ).

(4.1.14)

Note that

so that

Equation (4.1.14) shows that during the time τ , V1 is displaced a length s = vτ in the positive

ζ direction, i.e. V1 propagates with velocity v in the positive ζ direction. The conclusion is that

V (ζ ± vt) represents a plane wave that propagates at velocity v in the positive ζ direction (lower

sign) or in the negative ζ direction (upper sign).

4.2

Spherical waves

Consider now solutions of the scalar wave equation (4.0.1) of the form

V = V (r, t),

(4.2.1)

where

r = |r| =

x2 + y 2 + z 2 ,

(4.2.2)

FYS 263

13

is the distance from the origin (0, 0, 0). Since we have no angular dependence in this case, the

Laplacian operator has the following form in spherical coordinates (Exercise 3)

1 ∂2

(rV ),

r ∂r2

which upon substitution in the wave equation (4.0.1) gives

∇2 V =

∂2

1 ∂2

(rV

)

−

(rV ) = 0.

∂r2

v 2 ∂t2

Since (4.2.4) is of the same form as (4.1.8), the solution becomes (cf. (4.1.12))

rV = V1 (r − vt) + V2 (r + vt).

(4.2.3)

(4.2.4)

(4.2.5)

Thus, we have obtained the following result: V (r±vt)

represents a spherical wave that converges

r

towards the origin (upper sign) or diverges away from the origin (lower sign). Thus, V (r+vt)

propr

agates towards the origin with velocity v, whereas V (r−vt)

propagates

away

from

the

origin

with

r

velocity v.

4.3

Harmonic (monochromatic) waves

At a given point r in space the solution of the wave equation is a function only of time, i.e.

V (r, t) = F (t),

(4.3.1)

where F (t) can be an arbitrary function. If F (t) has the simple form

F (t) = a cos(ωt − δ),

(4.3.2)

then we have a harmonic wave in time. The quantities in (4.3.2) have the following meaning: a is the

amplitude (positive), ω is the angular frequency, and ωt − δ is the phase. A harmonic wave is also

called a monochromatic wave because it consists of only one frequency or wavelength component.

The frequency ν and the period T follow from

ω

1

= .

2π

T

The harmonic wave in (4.3.2) has period T because

ν=

F (t + T ) = a cos(ω(t + T ) − δ) = a cos(ωt − δ + 2π) = F (t).

(4.3.3)

(4.3.4)

From (4.1.12) we see that the general expression for a wave that propagates in the ŝ direction

can be written

r · ŝ

r · ŝ

V = V1 (r · ŝ − vt) = V1 −v t −

= V1 t −

,

(4.3.5)

v

v

where both V1 and V1 are arbitrary functions. By replacing t with t− r·ŝ

v in (4.3.2) we get a harmonic

plane wave

r · ŝ

V (r, t) = a cos ω t −

+ δ = a cos[kr · ŝ − ωt + δ],

(4.3.6)

v

where

ω

(4.3.7)

v

is the wave number. We see that that V (r, t) remains unchanged if we replace r · ŝ with r · ŝ + nλ,

where n = 1, 2, . . ., and λ is given by

k=

FYS 263

14

2π

2π

v

=v

= vT = .

(4.3.8)

k

ω

ν

The quantity λ is called the wavelength. Note that for t = constant, V (r, t) in (4.3.6) is periodic

with wavelength λ, i.e.

λ=

V (r · ŝ, t) = V (r · ŝ + nλ, t) ; n = 1, 2, 3, . . . .

(4.3.9)

Now we introduce the wave vector or propagation vector k, defined by

k = kŝ.

(4.3.10)

so that the expression (4.3.6) for a plane, harmonic wave can be written

V (r, t) = a cos(k · r − ωt + δ).

(4.3.11)

In a similar way the expression for a converging or a diverging harmonic spherical wave becomes

cos(∓kr − ωt + δ)

,

(4.3.12)

r

where the upper sign corresponds to a converging spherical wave and the lower sign to a diverging

spherical wave.

Consider now a plane, harmonic wave that propagates in the positive z direction, so that [cf.

(4.3.11)]

V (r, t) = a

V (z, t) = a cos(kz − ωt + δ).

(4.3.13)

A wave front is defined by the requirement that the phase shall be constant over it, i.e.

φ = kz − ωt + δ = constant.

(4.3.14)

Hence it follows that on a wave front we have

z = vt + constant ; v =

ω

.

k

(4.3.15)

Thus, the wave front propagates at the velocity

v=

ω

,

k

(4.3.16)

which is called the phase velocity.

4.4

Complex representation

Alternatively we can express (4.3.11) and (4.3.12) in the following way

V (r, t) = Re{U (r)e−iωt },

(4.4.1)

where Re{. . .} stands for the real part of {. . .}, and where the complex amplitude U (r) is given by

U (r) = aei(k·r+δ) ,

(4.4.2)

for a plane wave, and by

a i(±kr+δ)

,

e

r

for a diverging (upper sign) or converging (lower sign) spherical wave.

U (r) =

(4.4.3)

FYS 263

15

Note that when we perform linear operations, such as differentiation, integration or summation,

we can drop the ’Re’ symbol during the operations, as long as we remember to take the real part of

the result in the end.

By substituting

V (r, t) = U (r)e−iωt ,

(4.4.4)

(∇2 + k 2 )U (r) = 0,

(4.4.5)

in the wave equation (4.0.1), we get

which shows that the complex amplitude U (r) is a solution of the Helmholtz equation.

4.5

Linearity and the superposition principle

For any linear equation the sum of two or several solutions is also a solution. This is called the

superposition principle. Since Maxwell’s equations are linear, the superposition principle is valid

for electromagnetic waves as long as the material equations are linear. The superposition principle

implies that we can construct general solutions of the wave equation or Maxwell’s equations by

adding elementary solutions in the form of harmonic plane or spherical waves. We will discuss this

in detail in Part II.

4.6

Phase velocity and group velocity

Consider a harmonic wave of the form [cf. (4.3.11)]

V (r, t) = Re U (r)e−iωt ,

(4.6.1)

where the complex amplitude U (r) is a solution of the Helmholtz equation (4.4.5), i.e.

(∇2 + k 2 )U (r) = 0.

(4.6.2)

The wave number k can be written

ω

ω c

=

= k0 n,

v

c v

where k0 is the wave number in vacuum, i.e.

k=

k0 =

ω

,

c

(4.6.3)

(4.6.4)

and n is the refractive index given by

c √

= εµ.

(4.6.5)

v

A general wave V (r, t) can always be expressed as a sum of harmonic components. We will return

to this later. If ε depends on ω, i.e. ε = ε(ω), then the phase velocity also will depend on ω, since

v = nc = v(ω). This means that different harmonic components will propagate at different phase

velocities. A polychromatic wave or a pulse, which is comprised of many harmonic components,

therefore will change its shape during propagation, and the energy will not propagate at the phase

velocity, but at the group velocity, which is defined as

n=

dω

.

dk

If n(ω) = constant, we have a non-dispersive medium. Since

vg =

ω = vk,

(4.6.6)

(4.6.7)

FYS 263

16

where the phase velocity v =

c

n

now is constant, we have in this case

d

(vk) = v.

dk

Thus, the phase velocity and the group velocity are equal in a non-dispersive medium where n =

constant. In dispersive media we have

vg =

d

dv

dv

dv

(vk) = v + k

=v−λ

=v+ν ,

dk

dk

dλ

dν

ω

where the last two results follow from the relation k = 2π

λ = v.

vg =

4.7

(4.6.8)

Repetition

From Maxwell’s equations in source-free space (J = 0 ; ρ = 0) we find

εµ

εµ

Ë = 0 ; ∇2 H − 2 Ḧ = 0.

c2

c

Comparison of (4.7.1) with the scalar wave equation

∇2 E −

(4.7.1)

1

V̈ = 0,

(4.7.2)

v2

shows that any Cartesian component of E and H satisfies the scalar wave equation with phase

velocity v given by

∇2 V −

c

c

v=√ = .

εµ

n

(4.7.3)

The scalar wave equation (4.7.2) has simple solutions in the form of plane waves or spherical waves.

Plane waves

For a plane wave V is given by

V (r, t) = V1 (r · ŝ − vt) + V2 (r · ŝ − vt),

(4.7.4)

where V (ζ ∓ vt) represents a plane wave that propagates in the positive ζ direction (upper sign) or

in the negative ζ direction (lower sign).

Spherical waves

For a spherical wave V is given by

V (r, t) =

V1 (r − vt) V2 (r + vt)

+

,

r

r

(4.7.5)

represents a spherical wave that propagates away from the origin (upper sign) or

where V (r∓vt)

r

towards the origin (lower sign).

Harmonic (monochromatic) waves

A plane harmonic wave that propagates in the direction k = kŝ is given by

V (r, t) = a cos(k · r − ωt + δ),

(4.7.6)

and the corresponding spherical wave is

a

cos(±kr − ωt + δ),

(4.7.7)

r

where the upper sign represents a diverging spherical wave and the lower sign represents a converging

spherical wave.

V (r, t) =

FYS 263

17

Complex representation of harmonic waves

In complex notation we have

V (r, t) = Re[U (r)e−iωt ].

(4.7.8)

For a plane wave the complex amplitude U (r) is given by

U (r) = aei(k·r+δ) ,

and for a diverging or converging spherical wave it is given by

U (r) =

a i(±kr+δ)

e

.

r

By substituting (4.7.8) into the wave equation (4.7.2), we find that U (r) satisfies the Helmholtz

equation, i.e.

(∇2 + k 2 )U (r) = 0.

(4.7.9)

FYS 263

18

Chapter 5

Pulse propagation in a dispersive

medium

z

n(ω )

z=0

Figure 5.1: A plane wave propagates in the positive z direction in a dispersive medium that fills the

half space z ≥ 0.

Consider a polychromatic, plane wave that propagates in the positive z direction in a linear,

homogeneous, isotropic, and dispersive medium that fills the half space z > 0 (Fig. 5.1). The

polychromatic, plane wave u(z, t) is comprised of different harmonic components, which implies that

we can represent u(z, t) by the following inverse Fourier transform

∞

1

u(z, t) =

ũ(z, ω)e−iωt dω,

(5.1)

2π −∞

where the frequency spectrum ũ(z, ω) is given as the Fourier transform of u(z, t), i.e.

∞

ũ(z, ω) =

u(z, t)eiωt dt.

(5.2)

−∞

Thus, u(z, t) and ũ(z, ω) constitute a Fourier transform pair. Since ũ(z, ω) can be any Cartesian

component of the frequency spectrum of the electric or magnetic field, it satisfies the Helmholtz

equation, i.e.

[∇2 + k 2 (ω)]ũ(z, ω) = 0,

(5.3)

where

k(ω) =

ω

ω c

ω

=

= n(ω).

v(ω)

c v(ω)

c

(5.4)

FYS 263

19

Suppose now that u(z, t) is known for all values of t in the plane z = 0, and that u(0, t) vanishes for

t < 0.

Since there is no variation in the x and y directions, the Helmholtz equation (5.3) can be written

as

2

d

2

+

k

(ω)

ũ(z, ω) = 0,

(5.5)

dz 2

which has the following general solution

ũ(z, ω) = u+ (ω)eik(ω)z + u− (ω)e−ik(ω)z .

(5.6)

If we consider propagation in the positive z direction only, then u− (ω) = 0, so that (5.1) gives

∞

1

u(z, t) =

u+ (ω)ei(k(ω)z−ωt) dω.

(5.7)

2π −∞

Now we put z = 0 i (5.7), take an inverse Fourier transform, and use (??) to obtain

∞

u+ (ω) =

u(0, t)eiωt dt = ũ(0, ω),

(5.8)

−∞

so that (5.7) gives

u(z, t) =

1

2π

∞

ũ(0, ω)ei(k(ω)z−ωt) dω,

(5.9)

−∞

or

u(z, t) =

1

2π

∞

z

ũ(0, ω)ei c f (ω) dω,

(5.10)

−∞

where

ct

.

(5.11)

z

c

Consider first the special case in which n(ω) = v(ω)

= constant, which implies that we have a

ω

non-dispersive medium. Since k = v , where v now is constant, we have from (5.1) and (5.9)

∞

z

1

z

u(z, t) =

ũ(0, ω)e−iω(− v +t) dω = u 0, t −

.

(5.12)

2π −∞

v

f (ω) = ω[n(ω) − θ] ; θ =

This result shows that the pulse propagates in the positive z direction at velocity v without changing

its shape.

Suppose now that the medium is dispersive and that the frequency spectrum g̃(ω) of the pulse

in (5.10) does not contain singularities and that it is sufficiently wide. Then the main contribution

to the pulse in (5.10) comes from frequencies ωs for which the phase f (ω) in (5.11) is stationary, i.e.

from ωs that satisfy the equation

f (ωs ) = n(ωs ) − θ + ωs n (ωs ) = 0.

(5.13)

A model that is commonly used to study propagation in dispersive media, is the so called Lorentzmedium. For such a medium with one single resonance frequency the refractive index n(ω) is given

by the following expression

n(ω) = 1 −

b2

ω 2 − ω02 + 2δiω

1/2

,

(5.14)

where b is a constant, ω0 is the resonance frequency, and δ represents the damping (attenuation) in

the medium.

FYS 263

20

Equation (5.9) shows that when the medium is dispersive, then u(z, t) (for any z > 0) is a sum

of harmonic plane waves of the form ũ(0, ω)exp[i(k(ω)z − ωt)] = ũ(0, ω)exp[−ki (ω)z]exp[i(kr (ω)z −

ωt)], where kr (ω) and ki (ω) are the real and the imaginary part, repectively, of k(ω). Thus, the

amplitude ũ(0, ω)exp[−ki (ω)z], is damped exponentially as z increases, and the phase velocity is

given by v(ω) = krω(ω) , where k(ω) = (ω/c)n(ω) = (ω/c)[nr (ω) + ini (ω)] = kr (ω) + iki (ω). Since

the phase velocity v depends on the frequency ω, plane waves of different frequencies will arrive at

a given position z at different times and thus cause a distortion of the pulse, i.e. the shape of the

pulse will get changed. Also, the damping factor ki (ω) depends on ω, so that different frequency

components will have different amplitudes when they arrive at a given position z.

FYS 263

21

Chapter 6

General electromagnetic plane

wave

A general electromagnetic plane wave can be written in the form

E = E(k · r − ωt) ; H = H(k · r − ωt),

(6.1)

where k = kŝ, with ŝ pointing in the direction of propagation. We introduce a new variable u =

k · r − ωt, so that

∂u

= kx ;

∂x

∂u

= ky ;

∂y

∂u

= kz ;

∂z

∂u

= −ω.

∂t

(6.2)

In source-free space Maxwell’s equations (1.1.1)-(1.1.2) are given by

∇×H=

1

ε

Ḋ = Ė,

c

c

(6.3)

1

µ

∇ × E = − Ḃ = Ḣ.

(6.4)

c

c

By using the chain rule, we find that the x component of ∇ × E can be expressed as follows

(∇ × E)x

where E =

dE

du .

∂Ez

∂Ey

dEz ∂u dEy ∂u

−

=

−

∂y

∂z

du ∂y

du ∂z

ω

= Ez ky − Ey kz = (k × E )x = (ŝ × E )x ,

v

= ∇ y E z − ∇z E y =

(6.5)

By proceeding in a similar manner, we find that

∇×E=

ω

ŝ × E ,

v

(6.6)

∇×H=

ω

ŝ × H ,

v

(6.7)

where

dE

dH

; H =

.

du

du

(6.8)

∂E

dE ∂u

=

= −ωE ; Ḣ = −ωH .

∂t

du ∂t

(6.9)

E =

Further, we have

Ė =

FYS 263

22

By substitution of (6.6)-(6.9) into Maxwell’s equations (6.3)-(6.4) the result is

ε ε

ε c

ŝ × H = (−v)E = − √ E = −

E,

c

c εµ

µ

µ

µ ŝ × E = − (−v)H =

H,

c

ε

where we have used (3.9). Thus, we have

µ

ε

E =−

ŝ × H ; H =

ŝ × E .

ε

µ

(6.10)

(6.11)

(6.12)

By integrating over u in (6.12) and setting the integration constant equal to zero, we get

µ

ε

E=−

ŝ × H ; H =

ŝ × E.

ε

µ

(6.13)

Scalar multiplication of the equations in (6.13) with ŝ gives

ŝ · E = ŝ · H = 0,

(6.14)

which shows that both E and H are transverse waves, i.e. both E and H are normal to the propagation direction ŝ, as illustrated in Fig. 6.1. Thus, the vectors ŝ, E, and H represent a right-handed

Cartesian co-ordinate system.

E

^

s

H

Figure 6.1: The vectors E, H, and ŝ for an electromagnetic plane wave represent a right-handed

Cartesian co-ordinate system.

For the electric and the magnetic energy density we find

we =

ε 2

1

E·D=

E ; E = |E|,

8π

8π

(6.15)

µ 2

1

B·H=

H ; H = |H|.

8π

8π

√

√

Since µH = εE (cf. (6.13)), we get we = wm , and the total energy density becomes

wm =

w = we + wm = 2we =

1

1

εE 2 = 2wm =

µH 2 ,

4π

4π

(6.16)

(6.17)

and the Poynting vector (2.4) becomes

c

c

c

S=

E×H=

EHŝ =

E

4π

4π

4π

ε

Eŝ =

µ

1

εE 2

4π

c

√

εµ

ŝ = wvŝ.

(6.18)

FYS 263

23

Thus, we have

S = wvŝ,

(6.19)

which shows that the Poynting vector represents the energy flow, both with respect to absolute value

and direction. A dimensional analysis of (6.19) shows that

Energi m

Energi

W

= 2

= 2.

·

(6.20)

m3

s

m ·s

m

Thus, S represents the amount of energy per unit time that passes through a unit area of the plane

that is spanned by E and H, as asserted previously in chapter 2.

[|S|] = [w][v] =

FYS 263

24

Chapter 7

Harmonic electromagnetic waves of

arbitrary form - Time averages

The E and H fields for a harmonic wave of arbitrary form can be written

E = Re E0 (r)e−iωt

; H = Re H0 (r)e−iωt ,

(7.1)

where E0 (r) and H0 (r) are complex vectors. Thus, we have

I

E0 (r) = ER

0 (r) + iE0 ((r),

(7.2)

I

H(r) = HR

0 (r) + iH0 (r),

(7.3)

I

R

I

where ER

0 , E0 , H0 , and H0 are real vectors.

Since optical frequencies are very high (ω 1015 s−1 ), we can only observe averages of we , wm ,

and S, taken over a time interval −T ≤ t ≤ T , where T is much larger than the period T = 2π

ω .

For the time average of the electric energy density we have [cf. (2.1)]

1

we =

2T For any complex number z, we have Rez =

Therefore, we may write

T

−T 1

2 (z

E = Re[E0 (r)e−iωt ] =

ε

|E|2 dt.

8π

(7.4)

+ z ∗ ), where z ∗ is the complex conjugate of z.

1

[E0 e−iωt + E∗0 e+iωt ],

2

so that we get

|E|2 = E · E =

1

1

2iωt

]. (7.5)

[E0 e−iωt + E∗0 eiωt ] · [E0 e−iωt + E∗0 eiωt ] = [E20 e−2iωt + 2E0 · E∗0 + E∗2

0 e

4

4

Further, we have

1

2T T

−2iωt

e

−T T 1

1 e−2iωt

1

1 T

sin(2ωT ) =

dt =

=

sin(2ωT ).

2T

−2iω −T 2T

ω

4π T (7.6)

Since T T , the integral that includes the factor e−2iωt can be neglected. Similarly, the integral

that includes the factor e2iωt can be neglected, and we get

we =

ε

E0 · E∗0 .

16π

(7.7)

FYS 263

25

By proceeding in a similar manner, we find that the time average of the magnetic energy density

becomes

µ

H0 · H∗0 .

16π

The time average of the Poynting vector is given by [cf. (2.4)]

wm =

S =

1

2T T

−T c

(E × H)dt,

4π

(7.8)

(7.9)

where E × H can be written

E×H =

=

1

1

[E0 e−iωt + E∗0 eiωt ] × [H0 e−iωt + H∗0 eiωt ]

2

2

1

−2iωt

+ E0 × H∗0 + E∗0 × H0 + E∗0 × H∗0 e2iωt }.

{E0 × H0 e

4

(7.10)

By substituting (7.10) into (7.9) and performing time averaging, we find that the time average of

the Poynting vector becomes

S =

c

c

{E0 × H∗0 + E∗0 × H0 } =

Re(E0 × H∗0 ).

16π

8π

(7.11)

FYS 263

26

Chapter 8

Harmonic electromagnetic plane

wave – Polarisation

For an electromagnetic plane wave that is time harmonic, each Cartesian component of E and H is

of the form

a cos(τ + δ) = Re[aei(τ +δ) ] ; a > 0,

(8.1)

τ = k · r − ωt.

(8.2)

where

Let the z axis point in the ŝ direction. Then only the x and y components of E and H are non-zero,

since the electromagnetic field of a plane wave is transverse.

Now we want to determine that curve which the end point of the electric vector describes during

propagation. This curve consists of points that have co-ordinates (Ex , Ey ) given by

Ex = a1 cos(τ + δ1 ) ; a1 > 0,

(8.3)

Ey = a2 cos(τ + δ2 ) ; a2 > 0,

(8.4)

Ez = 0.

(8.5)

In order to determine that curve which E(τ ) describes (Fig. 8.1), we eliminate τ from (8.3)-(8.4).

We let β = τ + δ1 and get

Ex = a1 cos β,

(8.6)

Ey = a2 cos(β + δ) = a2 [cos β cos δ − sinβ sin δ],

(8.7)

where δ = δ2 − δ1 . We substitute from (8.6) into (8.7) and get

2

Ey

Ex

Ex

=

cos δ − 1 −

sin δ,

a2

a1

a1

(8.8)

which upon squaring gives

Ex

a1

2

+

Ey

a2

2

−2

Ex Ey

cos δ = sin2 δ.

a1 a2

(8.9)

This is the equation of a conic section. The cross term implies that it is rotated relative to the

co-ordinate axes (x, y). By letting δ = π2 , we get

FYS 263

27

x

E x (τ )

E(τ )

z

E y (τ )

y

Figure 8.1: Instantaneous picture of the electric vector of a plane wave that propagates in the z

direction.

Ex

a1

2

+

Ey

a2

2

= 1,

(8.10)

which shows that the equation describes an ellipse. In a co-ordinate system (ξ, η), which coincides

with the axes of the ellipse, the equations for the field components become

Eξ = a cos(τ + δ0 ),

(8.11)

Eη = ±b sin(τ + δ0 ),

(8.12)

which upon squaring gives

Eξ

a

2

+

Eη

b

2

= 1.

(8.13)

When τ + δ0 = 0, we have Eξ = a; Eη = 0, and when τ + δ0 = π2 , we have Eξ = 0; Eη = ±b. This

shows that when the upper or lower sign in (8.12) applies, the electric vector rotates against or with

the clock, respectively, if we view the xy plane from the positive z axis. Rotation against the clock

is called left-handed polarisation, and rotation with the clock is called right-handed polarisation.

The relation between the two co-ordinate systems (x, y) and (ξ, η) is shown in Fig. 8.2, where

(cf. Exercise 7)

a2 + b2 = a21 + b22 ,

tan 2ψ = tan(2α) cos δ ; tan α =

(8.14)

π

a2

(0 ≤ α ≤ ),

a1

2

(8.15)

b

sin 2ψ = sin(2α) sin δ ; tan ψ = ± .

(8.16)

a

Since sin δ < 0 when the upper sign in (8.12) applies, we have left-handed polarisation when sin δ < 0.

We consider now some special cases of (8.6)-(8.7).

Linear polarisation.

If the phase difference δ is equal to an integer times π, i.e. if

δ = mπ (m = 1, ±1, ±2, . . .),

(8.17)

Ex = a1 cos β,

(8.18)

then we get from (8.6)-(8.7)

FYS 263

28

y

η

ξ

a

b

ψ

2a 2

x

2a1

Figure 8.2: The end point of the electric vector describes an ellipse that is inscribed in a rectangle

with sides 2a1 and 2a2 .

Ey = a2 cos(β + mπ) = a2 (−1)m

Ex

,

a1

(8.19)

which shows that the ellipse degenerates into a straight line, i.e.

Ey

a2

= (−1)m .

Ex

a1

Circular polarisation.

of 2π, i.e. if

(8.20)

If the amplitudes are equal and the phase difference is ± π2 plus a multiple

a1 = a2 ,

π

+ 2mπ (m = 0, ±1, ±2, . . .),

2

then the ellipse in (8.6)-(8.7) degenerates into a circle, i.e.

δ=±

Ex = a cos β,

π

Ey = a cos β + 2mπ ±

= ∓a sin β.

2

By squaring these two equations, we get

Ex2 + Ey2 = a2 .

(8.21)

(8.22)

(8.23)

(8.24)

(8.25)

We have right-handed circular polarisation when Ey = −a sin β and left-handed circular polarisation

when Ey = +a sin β.

FYS 263

29

Chapter 9

Reflection and refraction of a plane

wave

k

r

k

θr

t

θt

^

n=^

ez

θi

ki

ε2 , µ

ε1, µ 1

2

Figure 9.1: Reflection and refraction of a plane wave at a plane interface between two different

media. Illustration of propagation directions and angles of incidence, reflection, and transmission.

We let a plane wave be incident upon a plane interface between two different media, as shown in

Fig. 9.1. The incident wave gives rise to a reflected wave and a transmitted wave, which we assume

are plane waves as well. Thus, each component of E or H can be written

q

Aqj = Re{aqj ei(k

·r−ωt)

} (j = x, y, z) ,

(9.0.1)

where A stands for E or H and q = i, r, t, so that ki , kr , and kt are the wave vectors of the incident,

reflected, and transmitted waves, respectively.

9.1

Reflection law and refraction law (Snell’s law)

The existence of continuity conditions that E and H must satisfy at the interface between the two

media in Fig. 9.1, implies that when r represents a point at the interface, the argument in the

exponential function in (9.0.1) must be the same for the reflected and transmitted waves as for the

incident wave. Thus, we have

FYS 263

30

^t =

θ

^n x ^b

^n

i

k

i

^

^

ki x n

b = ___________

i

^|

| k x n

Figure 9.2: Reflection and refraction of a plane wave. Illustration of the co-ordinate system (n̂, b̂,

t̂).

ki · r − ωt = kr · r − ωt = kt · r − ωt,

(9.1.1)

ki · r = kr · r = kt · r.

(9.1.2)

or

Now we introduce a Cartesian co-ordinate system in which the unit vectors n̂, b̂, and t̂ represent

a right-handed system (Fig. 9.2). Let n̂ point along the interface normal into the medium of the

refracted wave, and let b̂ and t̂ be defined by

b̂ =

ki × n̂

; t̂ = n̂ × b̂.

|ki × n̂|

(9.1.3)

In this co-ordinate system we have

ki = kti t̂ + kni n̂ ; kbi = ki · b̂ = 0,

(9.1.4)

kr = ktr t̂ + knr n̂ + kbr b̂,

(9.1.5)

kt = ktt t̂ + knt n̂ + kbt b̂,

(9.1.6)

r = rt t̂ + rb b̂.

(9.1.7)

i

Note that the co-ordinate system is defined such that k has no component along b̂, i.e. b̂ is normal

to the plane of incidence, which is spanned by the vectors ki and n̂.

Since

ki · r = (kti t̂ + kni n̂) · (rt t̂ + rb b̂) = kti rt ,

(9.1.8)

kr · r = (ktr t̂ + knr n̂ + kbr b̂) · (rt t̂ + rb b̂) = ktr rt + kbr rb ,

(9.1.9)

kt · r = (ktt t̂ + knt n̂ + kbt b̂) · (rt t̂ + rb b̂) = ktt rt + kbt rb ,

(9.1.10)

it follows from the continuity condition (9.1.2) that

kti rt = ktr rt + kbr rb = ktt rt + kbt rb .

(9.1.11)

FYS 263

31

But since (9.1.11) shall apply to any point at the interface, i.e. to all values of rt and rb , we must

have

kbr = kbt = 0.

(9.1.12)

Thus, both kr and kt must lie in the plane of incidence spanned by ki and n̂. Therefore, we have

kti = ktr = ktt = kt ,

i

r

(9.1.13)

t

which implies that the components of k , k , and k parallel to the interface are equal. By using

n̂ × kq = n̂ × (kt t̂ + knq n̂) = −b̂kt ; q = i, r, t,

(9.1.14)

n̂ × ki = n̂ × kr ,

(9.1.15)

n̂ × kt = n̂ × ki .

(9.1.16)

we find that

Further, we use the relation |a × b| = |a||b| sin θ, where θ is the angle between the vectors a and b.

Thus, we find from (9.1.15) and Fig. 9.1 that

k i sin θi = k r sin θr .

i

(9.1.17)

r

Also, we know that k = k = n1 k0 , where n1 is the refractive index in medium 1, and k0 is the

wave number in vacuum. The reflection law therefore becomes

θi = θr ,

(9.1.18)

which in (9.1.15) is given in vectorial form.

From (9.1.16) and Fig. 9.1 we get the refraction law or Snell’s law

k i sin θi = k t sin θt .

(9.1.19)

which by using k i = n1 k0 and k t = n2 k0 , becomes

n1 sin θi = n2 sin θt .

(9.1.20)

Equation (9.1.16) represents Snell’s law in vector form. Note that (9.1.15) and (9.1.16) contain more

information than (9.1.18) and (9.1.20). From the vector equations it is clear that kr and kt lie in

the plane of incidence.

9.2

Generalisation of the reflection law and Snell’s law

The reflection law and Snell’s law (the refraction law) can be generalised to include non-planar waves

that are incident upon a non-planar interface. This is illustrated in Fig. 9.3, where the field from a

point source propagates towards a curved interface. Suppose now that the distance from the point

source to the interface is much larger than the wavelength. Then at each point on the interface we

may consider the incident wave to be a plane wave locally, and we may replace the interface locally

by the tangent plane through the point in question. Then we can use Snell’s law and the reflection

law as derived for a plane wave that is incident upon a plane interface, as illustrated in Fig. 9.3.

FYS 263

32

kr

θ

local tangent plane

r

kt

θ

i

θt

^n

ki

n1

n2

Point source

Figure 9.3: Generalisation of Snell’s law and the reflection law to include non-planar waves that are

incident upon a curved interface.

9.3

Reflection and refraction of plane electromagnetic waves

Note that the reflection law and the refraction law apply to all types of plane waves, i.e. to acoustic,

electromagnetic, and elastic waves. In the derivation we have only used that kq · r − ωt (q = i, r, t)

shall be the same for q = i, q = r, and q = t. Now we take a closer look at the reflection and

refraction of plane electromagnetic waves in order to determine how much of the energy in the

incident wave that is reflected and transmitted.

We know that a plane electromagnetic wave is transverse, i.e. that both E and B = µH are

normal to the propagation direction k = kŝ. In Fig. 9.1 we have chosen the z axis in the direction of

the interface normal. If E is normal to the plane of incidence, we have s polarisation (from German,

“Senkrecht”) or T E polarisation (“transverse electric” relative to the plane of incidence or the z

axis). And if E is parallel with the plane of incidence, we have p polarisation or T M polarisation,

since in this case B is normal to the plane of incidence or the z axis; hence the use of the term T M

or “transverse magnetic”.

A general time-harmonic, plane electromagnetic wave consists of both a T E and a T M component. With the time dependence e−iωt suppressed, we have for the spatial part of the field

E = ET E + ET M ; B = BT E + BT M ,

kt × êz ik·r

e ,

kt

(9.3.2)

k × (kt × ê)z ik·r

e ,

kkt

(9.3.3)

ET E = E T E

ET M = E T M

k × (kt × êz ) ik·r

1

k × ET E = E T E

e ,

k0

k0 kt

(9.3.4)

1

1

k × ET M = E T M

k × [k × (kt × êz )]eik·r .

k0

k0 kkt

(9.3.5)

BT E =

BT M =

(9.3.1)

But since k × [k × (kt × êz )] = k[k · (kt × êz )] − (kt × êz )k · k = −k 2 kt × êz , we get

BT M =

−k T M kt × êz ik·r

E

e .

k0

kt

(9.3.6)

FYS 263

33

Note that the vectors

êT E =

kt × êz

kt

; êT M =

k × (kt × êz )

,

kkt

(9.3.7)

are unit vectors in the directions of ET E and ET M , respectively.

We represent each of the incident, reflected, and transmitted fields in the manner given above,

so that (q = i, r, t)

Eq = ET Eq + ET M q ; Bq = BT Eq + BT M q ,

kt × êz ikq ·r

e

,

kt

(9.3.9)

kq × (kt × êz ) ikq ·r

e

,

k q kt

(9.3.10)

ET Eq = E T Eq

ET M q = E T M q

BT Eq =

(9.3.8)

k q T Eq kq × (kt × êz ) ikq ·r

E

e

,

k0

k q kt

(9.3.11)

−k q T M q kt × êz ikq ·r

E

e

,

k0

kt

(9.3.12)

BT M q =

where

ki = kt + kz1 êz ; kt = kx êx + ky êy ,

(9.3.13)

kr = kt − kz1 êz ; kt = kt + kz2 êz ,

(9.3.14)

kq =

k1 = n1 k0

k2 = n2 k0

for q = i, r

for q = t.

(9.3.15)

The continuity conditions that must be satisfied at the interface z = 0 are that the tangential

components of E and H = µ1 B be continuous, i.e.

êz × ET Ei + ET Er − ET Et + ET M i + ET M r − ET M t = 0,

êz ×

1 T Ei

1 T Mi

1 T Et

1 T Mt

+ BT Er −

B

+

+ BT M r −

B

B

B

µ1

µ2

µ1

µ2

(9.3.16)

= 0.

(9.3.17)

Further, we have

êz × [kq × (kt × êz )] = (kq · êz ) êz × kt ,

(9.3.18)

êz × (kt × êz ) = kt .

(9.3.19)

By substituting from (9.3.9)-(9.3.12) into the boundary conditions (9.3.16)-(9.3.17) and using (9.1.2)

and (9.3.18)-(9.3.19), we get

kz1 T M i kz1 T M r kz2 T M t

kt E T Ei + E T Er − E T Et + êz × kt

E

−

E

−

E

= 0,

(9.3.20)

k1

k1

k2

1 kz1 T Ei kz1 T Er

1 kz2 T Et

êz × kt

−

E

−

E

E

µ1 k0

k0

µ2 k0

1 −k1 T M i k1 T M r

−k2 T M t

+kt

−

= 0.

(9.3.21)

E

− E

E

µ1

k0

k0

k0

FYS 263

34

Since kt and êz × kt are orthogonal vectors, the expression inside each of the {} parentheses in

(9.3.20) and (9.3.21) must vanish, i.e.

E T Ei + E T Er = E T Et ,

(9.3.22)

kz1 µ2 E T Ei − E T Er = kz2 µ1 E T Et ,

(9.3.23)

kz1 k2 E T M i − E T M r = kz2 k1 E T M t ,

(9.3.24)

k1 µ2 E T M i − E T M r = k2 µ1 E T M t .

(9.3.25)

Now we define reflection and transmission coefficients as

RT E =

E T Er

E T Ei

; TTE =

E T Et

,

E T Ei

(9.3.26)

RT M =

ET Mr

ET Mi

; TTM =

ET Mt

,

ET Mi

(9.3.27)

kz2 µ1 T E

T ,

kz1 µ2

(9.3.28)

so that (9.3.22)-(9.3.25) give

1 + RT E = T T E ; 1 − RT E =

1 − RT M =

kz2 k1 T M

k2 µ1 T M

T

; 1 + RT M =

T

.

kz1 k2

k1 µ2

(9.3.29)

The two equations in (9.3.28) have the following solution

RT E =

µ2 kz1 − µ1 kz2

µ2 kz1 + µ1 kz2

; TTE =

2µ2 kz1

,

µ2 kz1 + µ1 kz2

(9.3.30)

; TTM =

2k1 k2 µ2 kz1

.

k22 µ1 kz1 + k12 µ2 kz2

(9.3.31)

whereas the two equations in (9.3.29) give

k22 µ1 kz1 − k12 µ2 kz2

k22 µ1 kz1 + k12 µ2 kz2

RT M =

The interpretation of the reflection and transmission coefficients follow from (9.3.26)-(9.3.27). Thus,

the reflection coefficient represents the amplitude ratio between the reflected and the incident E

field, whereas the transmission coefficient represents the amplitude ratio between the transmitted

and the incident E field.

Note that (9.3.22)-(9.3.23) and (9.3.28) contain only T E quantities, whereas equations (9.3.24)(9.3.25) and (9.3.29) contain only T M quantities. This implies that these two wave types are

independent or de-coupled upon reflection and refraction. Thus, an incident T E plane wave produces

a reflected T E plane wave and a transmitted T E plane wave, whereas an incident T M plane wave

produces a reflected T M plane wave and a transmitted T M plane wave. Upon reflection and

refraction there is no coupling between T E and T M waves.

From Fig. 9.1 it follows that

kz1 = ki · êz = k1 cos θi ; kz2 = kt · êz = k2 cos θt ,

(9.3.32)

so that if µ1 = µ2 = 1 the reflection and transmission coefficients become

TTM =

2n1 cos θi

n2 cos θi + n1 cos θt

TTE =

; RT M =

n2 cos θi − n1 cos θt

,

n2 cos θi + n1 cos θt

2n1 cos θi

n1 cos θi − n2 cos θt

; RT E =

,

i

t

n1 cos θ + n2 cos θ

n1 cos θi + n2 cos θt

(9.3.33)

(9.3.34)

FYS 263

35

^e TMt

e^ TMr

k

r

kt

k

i

r

i

θ =θ

k

t

θt

^

ez

θi

^e TMi

n1

ki

n2

^e TEi = ^e TEr = ^e TEt

=

^e TE

z=0

Figure 9.4: Reflection and refraction of a plane electromagnetic wave at a plane interface between

two different media. Illustration of T E and T M components of the electric field.

These expressions are called the Fresnel formulas. By using Snell’s law (9.1.20), we can rewrite them

as (Exercise 9)

TTM =

2 sin θt cos θi

tan(θi − θt )

; RT M =

,

t

i

t

+ θ ) cos(θ − θ )

tan(θi + θt )

sin(θi

TTE =

2 sin θt cos θi

sin(θi + θt )

; RT E = −

sin(θi − θt )

.

sin(θi + θt )

(9.3.35)

(9.3.36)

At normal incidence where θi = θt = 0, we get from (9.3.33) and (9.3.34)

TTE = TTM =

n2

2

n−1

; RT M = −RT E =

; n=

.

n+1

n+1

n1

(9.3.37)

The fact that RT M = −RT E at normal incidence follows from the way in which ET E and ET E

are defined. From Fig. 9.4 we see that these two vectors point in opposite directions at normal

incidence.

9.3.1

Reflectance and transmittance

Fig. 9.4 shows the polarisation vectors êT M q (q = i, r, t) and êT E for T M and T E polarisation.

These unit vectors are parallel with the electric field and follow from (9.3.9)-(9.3.12)

êT Ei = êT Er = êT Et = êT E =

êT M q =

kt × êz

kt

; |êT E | = 1,

kq × (kt × êz )

; |êT M q | = 1.

k q kt

(9.3.38)

(9.3.39)

Let the angle between Eq and the plane of incidence spanned by kq and êT M q , be αq [see Fig. 9.5],

so that

Eq = êT E E q sin αq + êT M q E q cos αq .

(9.3.40)

FYS 263

36

E

q

^e TMq

^e TEq

E TEq

q

α

E TMq

q

k

Figure 9.5: Illustration of the angle αq between the electric vector Eq and the plane of incidence

spanned by kq and êT M q .

Further, we let J i , J r , and J t denote the energy flows of respectively the incident, reflected, and

transmitted fields per unit area of the interface. Then we have

J pq = S pq cos θq ; p = T E, T M ; q = i, r, t,

(9.3.41)

where S pq is the absolute value of the Poynting vector, given by

q

ε

c pq

c pq pq

c

2

pq

pq

S =

(E pq ) .

(9.3.42)

|E × H | =

E H =

4π

4π

4π µq

√

√

Here we have used the relation εq E pq = µq H pq . The reflectance Rp (p = T E, T M is the ratio

between the reflected and incident energy flows. From (9.3.41)-(9.3.42) we have

RT M =

RT E =

JT Mr

|E T M r |2

=

= (RT M )2 .

T

M

i

J

|E T M i |2

(9.3.43)

J T Er

|E T Er |2

=

= (RT E )2 ,

J T Ei

|E T Ei |2

(9.3.44)

Thus, the reflectance Rp is equal to the square of reflection coefficient Rp .

The transmittance T p (p = T E, T M ) is the ratio between the transmitted and incident energy

flows, and (9.3.41)-(9.3.42) give

T TM =

JT Mt

n2 µ1 cos θt T M 2

=

(T

) ,

JT Mi

n1 µ2 cos θi

(9.3.45)

T TE =

J T Et

n2 µ1 cos θt T E 2

=

(T ) .

J T Ei

n1 µ2 cos θi

(9.3.46)

Thus, the transmittance T p is proportional to the square of the transmission coefficient T p (p =

T E, T M ). When µ2 = µ1 = 1, we find on substitution from (9.3.35)-(9.3.36) into (9.3.43)-(9.3.46)

the following expressions for the reflectance and the transmittance

RT M =

tan2 (θi − θt )

,

tan2 (θi + θt )

(9.3.47)

FYS 263

37

sin2 (θi − θt )

,

sin2 (θi + θt )

(9.3.48)

sin 2θi sin 2θt

,

sin2 (θi + θt ) cos2 (θi − θt )

(9.3.49)

sin 2θi sin 2θt

.

sin2 (θi + θt )

(9.3.50)

RT E =

T TM =

T TE =

By use of these formulas one can show that

RT M + T T M = 1 ; RT E + T T E = 1,

(9.3.51)

so that for each of the two polarisations the sum of the reflected energy and the transmitted energy

is equal to the incident energy.

From (9.3.41) and (9.3.42) we have

ε1 pi 2

c

J pi =

|E | cos θi ,

(9.3.52)

4π µ1

which by the use of (9.3.40) gives

JT Mi

c

4π

ε1 T Ei 2

c

|E

| = cos θi

µ1

4π

ε1 2 2 i

E sin α ,

µ1

c

ε1 T M i 2

c

ε1 2

= cos θi

|E

| = cos θi

E cos2 αi .

4π µ1

4π µ1

J T Ei = cos θi

(9.3.53)

(9.3.54)

But since the total incident energy flow is given by

J i = cos θi

c

4π

ε1 2

E ,

µ1

(9.3.55)

we find

J T Ei = J i sin2 αi ; J T M i = J i cos2 αi .

(9.3.56)

Thus, we have

R=

Jr

J T M r + J T Er

JT Mr

J T Er

=

= T M i cos2 αi + T Ei sin2 αi ,

i

i

J

J

J

J

(9.3.57)

which gives

R = RT M cos2 αi + RT E sin2 αi ,

(9.3.58)

T = T T M cos2 αi + T T E sin2 αi .

(9.3.59)

and similarly we find

i

t

At normal incidence, θ = θ = 0, and the distinction between T E and T M polarisation disappears.

From (9.3.43)-(9.3.46) combined with (9.3.33)-(9.3.34), we find (when µ1 = µ2 = 1)

2

R = RT M = RT E = (RT E )2 = RT M =

2 2

T = T TM = T TE = TTE = TTM =

n−1

n+1

2

4n

(n + 1)2

; n=

; n=

n2

,

n1

n2

.

n1

(9.3.60)

(9.3.61)

When n → 1, we see that R → 0 and T → 1, as expected. Similarly, we find from (9.3.47)-(9.3.50)

that R → 0, R⊥ → 0, T → 1, T⊥ → 1 when n → 1.

FYS 263

38

kr

ki

θ iB

θ iB

1

2

θ tB

kt

Figure 9.6: Illustration of Brewster’s law.

9.3.2

Brewster’s law

From (9.3.47) it follows that RT M = 0 when θi + θt = π2 , since then tan(θi + θt ) = ∞. We call this

particular angle of incidence θiB and the corresponding refraction or transmission angle θtB . By

using Snell’s law (9.1.20), we find

π

n2 sin θtB = n2 sin

− θiB = n2 cos θiB = n1 sin θiB ,

(9.3.62)

2

so that RT M = 0 when θi = θiB , where θiB is given by

tan θiB =

n2

= n.

n1

(9.3.63)

The angle θiB is called the polarisation angle or the Brewster angle. When the angle of incidence

is equal to θiB , the E vector of the reflected light has no component in the plane of incidence (Fig.

9.6). This fact is exploited in sunglasses with polarisation filter. The filter is oriented such that

only light that is polarised vertically (Fig. 9.6) is transmitted. Thus, one avoids to a certain degree

annoying reflections from e.g. a water surface.

Note that kr · kt = 0, i.e. kr and kt are normal to one another when θi = θiB , as shown in

Fig. 9.6.

9.3.3

Unpolarised light (natural light)

For natural light, e.g. light from an incandescent lamp, the direction of the E vector varies very

rapidly in an arbitrary or irregular manner, so that no particular direction is given preference. The

average reflectance R is obtained by averaging over all directions α. Since the average value of both

sin2 α and cos2 α is 12 , we find from (9.3.56) that

J

T Mi

= J i cos2 αi = J

T Ei

= J i sin2 αi =

1 i

J .

2

(9.3.64)

For the reflected components we find

J

T Mr

=

J

J

T Mr

T Mi

·J

T Mi

=

J

J

T Mr

T Mi

1

1

· J i = RT M J i ,

2

2

(9.3.65)

FYS 263

39

J

T Er

=

J

T Er

T Ei

1

1

· J i = RT E J i ,

2

2

J

which shows that the degree of polarisation for the reflected light can be defined as

TM

R

− RT E |J T M r − J T Er |

r

P = TM

= T Mr

.

R

+ RT E J

+ J T Er

(9.3.66)

(9.3.67)

The average reflectance is given by

R=

J

J

r

i

=

J

T Mr

+J

J

T Er

J

=

i

T Mr

2J

T Mi

+

J

T Er

2J

T Ei

=

1 TM

+ RT E ,

R

2

(9.3.68)

so that the degree of polarisation becomes

1 1 TM

− RT E |,

|R

R2

where |RT M − RT E | is called the polarised part of the reflected light.

Similarly, we find for the transmitted light

Pr =

T =

9.3.4

1 TM

1 1 TM

+ T TE) ; P t =

− T T E |.

(T

|T

2

T 2

(9.3.69)

(9.3.70)

Rotation of the plane of polarisation upon reflection and refraction

Note that if the incident light is linearly polarised, then also the reflected and the transmitted light

will be linearly polarised, since the phases only change by 0 or π. This follows from the fact that the

reflection and transmission coefficients are real quantities [cf. (9.3.33)-(9.3.36)]. But the planes of

polarisation for the reflected and the transmitted light are rotated in opposite directions relative to

the polarisation plane of the incident light. The angles αi , αr , and αt that the planes of polarisation

of the incident, reflected, and transmitted light form with the plane of incidence, are given by [cf.

Fig. 9.5]

tan αi =

E T Ei

,

ET Mi

(9.3.71)

E T Er

tan α = T M r =

E

E T Er

E T Ei

ET M r

ET M i

E T Ei

RT E

=

tan αi ,

ET Mi

RT M

(9.3.72)

E T Et

tan α = T M t =

E

E T Et

E T Ei

ET M t

ET M i

E T Ei

TTE

=

tan αi .

ET Mi

TTM

(9.3.73)

r

t

By use of the Fresnel formulas (9.3.35)-(9.3.36) we can write

tan αr = −

cos(θi − θt )

tan αi ,

cos(θi + θt )

tan αt = cos(θi − θt ) tan αi .

Since 0 ≤ θi ≤

π

2

and 0 ≤ θt ≤

π

2,

(9.3.74)

(9.3.75)

we get

| tan αr | ≥ | tan αi |,

(9.3.76)

| tan αt | ≤ | tan αi |.

i

(9.3.77)

t

In (9.3.76) the equality sign applies at normal incidence (θ = θ = 0) and at grazing incidence (θi =

π

2 ), whereas in (9.3.77) the equality sign applies only at normal incidence. These two inequalities

FYS 263

40

imply that upon reflection the plane of polarisation is rotated away from the plane of incidence,

whereas upon transmission it is rotated towards the plane of incidence. Note that when θi = θiB ,

so that θiB + θtB = π2 , then tan αr = ∞. Thus, we have αr = π2 in accordance with Brewster’s law.

9.3.5

Total reflection

Snell’s law (9.1.20) can be written in the form

sin θt =

sin θi

n

; n=

n2

=

n1

ε2 µ2

.

ε1 µ1

(9.3.78)

Hence, it follows that if n < 1, then we get sin θt = 1 when θi = θic , where

sin θic = n.

(9.3.79)

This implies that when θi = θic , we get θt = π2 , so that the transmitted light propagates along the

interface. If θi ≥ θic , we have total reflection, i.e. no light will pass into the other medium. All

light is then reflected. There exists a field in the other medium, but there is no energy transport

through the interface. When θi > θic , then sin θt > 1, which means that θt is complex. We have

from (9.3.78)

sin2 θi

±i sin2 θi − n2

2 t

t

cos θ = ± 1 − sin θ = ±i

−1=

.

(9.3.80)

n2

n

The lower sign in (9.3.80) must be discarded. Otherwise the field in medium 2 would grow exponentially with increasing distance from the interface. The electric field in medium 2 is

t

Ept = T p E pi êpt ei(k

·r−ωt)

(p = T E, T M ),

(9.3.81)

where

kt · r = kx x + ky y + kz2 z,

(9.3.82)

with (cf. Fig. 9.1 and (9.3.80) with upper sign)

kz2 = k2 cos θt = ik2

1 2 i

n2

sin θ − n2 ; n =

,

n

n1

(9.3.83)

so that

k2 2 i

sin θ − n2 .

(9.3.84)

n

We see that Ept represents a wave that propagates along the interface and is exponentially damped

with the distance z into medium 2.

From ∇ · Dt = ε2 ∇ · Et = 0 it follows that

t

eik

·r

= ei(kx x+ky y) e−|kz2 |z ; |kz2 | =

kt · Et = 0,

(9.3.85)

which gives

Ezt = −

(kx Ext + ky Eyt )

.

kz2

(9.3.86)

If we let the plane of incidence coincide with the xz plane, we have (cf. Fig. 9.7)

kx = −k1 sin θi ; ky = 0,

(9.3.87)

Eyt = E T Et ei(kx x−ωt) e−|kz2 |z = T T E E T Ei ei(kx x−ωt) e−|kz2 |z ,

(9.3.88)

FYS 263

41

E TMr

kt

kr

θi

θt

k

E TMt

i

θt

z

θi

E TMi

E TEi = E TEr = E TEt

ki

x

Figure 9.7: Illustration of the refraction of a plane wave into an optically thinner medium, so that

θi < θt . When θi → θic , then θt → π/2, and we get total reflection.

Ext = −E T M t cos θt ei(kx x−ωt) e−|kz2 | = −T T M E T M i cos θt ei(kx x−ωt) e−|kz2 |z ,

Ezt = −

kx t

kx T M T M i i(kx x−ωt) −|kz2 |z

Ex =

T

E

e

e

.

kz2

k2

(9.3.89)

(9.3.90)

From these expressions for the components of Et and corresponding expressions for the components

of Ht one can show (Exercise 11) that the time average of the z component of the Poynting vector

is zero, which implies that there is no energy transport through the interface, as asserted earlier.

The reflection coefficients in (9.3.35)-(9.3.36) can be written as follows

RT M =

sin θi cos θi − sin θt cos θt

,

sin θi cos θi + sin θt cos θt

(9.3.91)

sin θi cos θt − sin θt cos θi

.

sin θi cos θt + sin θt cos θi

(9.3.92)

RT E = −

By combining Snell’s law (9.3.78) and (9.3.80) with the upper sign with (9.3.91)-(9.3.92), we get

n2 cos θi − i sin2 θi − n2

TM

R

=

,

(9.3.93)

n2 cos θi + i sin2 θi − n2

i

−

i

sin2 θi − n2

cos

θ

RT E =

.

(9.3.94)

cos θi + i sin2 θi − n2

Since both reflection coefficients are of the form z/z ∗ , where z is a complex number, it follows that

|RT M | = |RT E | = 1,

(9.3.95)

FYS 263

42

which shows that for each polarisation the intensity of the totally reflected light is equal to the

intensity of the incident light.

But the phase is altered upon total reflection. Letting

Rp =

p

p

E pr

zp

= eiδ = p = e2iα (p = T E, T M ),

pi

E

z ∗

(9.3.96)

where [cf. (9.3.93)-(9.3.94)]

TM

z T M = n2 cos θi − i sin2 θi − n2 = |z T M |eiα ,

(9.3.97)

TE

z T E = cos θi − i sin2 θi − n2 = |z T E |eiα ,

(9.3.98)

we find

tan α

TM

= tan

tan α

TE

= tan

1 TM

δ

2

1 TE

δ

2

=−

=−

sin2 θi − n2

,

n2 cos θi

(9.3.99)

sin2 θi − n2

.

cos θi

(9.3.100)

The relative phase difference

δ = δT E − δT M ,

(9.3.101)

is determined by

tan

1

δ

2

tan 12 δ T E − tan 12 δ T M

,

=

1 + tan 12 δ T E tan 12 δ T M

which upon substitution from (9.3.99)-(9.3.100) gives

1

cos θi sin2 θi − n2

tan

.

δ =

2

sin2 θi

(9.3.102)

(9.3.103)

We see that δ = 0 for θi = π2 (grazing incidence) and θi = θic (critical angle of incidence). Between

these two values there is an angle of incidence θi = θim which gives a maximum phase difference

δ = δ m , where θim is determined by

dδ = 0.

(9.3.104)

dθi θim

From (9.3.104) we find

2n2

,

1 + n2

which upon substitution in (9.3.103) gives (Exercise 10)

1 m

1 − n2

tan

=

δ

.

2

2n

sin2 θim =

(9.3.105)

(9.3.106)

If the phase difference δ is equal to ± π2 and in addition E T M i = E T Ei , the totally reflected light

will be circularly polarised. By choosing the angle αi between the polarisation plane and the plane

of incidence equal to 45◦ , we make E T M i equal to E T Ei . In order to obtain δ = π2 we must have

δm δm

π

≥ tan π4 = 1, which according to (9.3.106) implies that

2 ≥ 4 . This means that tan

2

n2 + 2n − 1 ≤ 0.

By completing the square on the left-hand side of (9.3.107), we find that

(9.3.107)

FYS 263

43

n≤

√

2−1 ;

√

1

n1

≥ 2 + 1 = 2.41.

=

n

n2

Thus, nn12 must exceed 2.41 in order that we shall obtain a phase difference of

reflection.

(9.3.108)

π

2

in one single