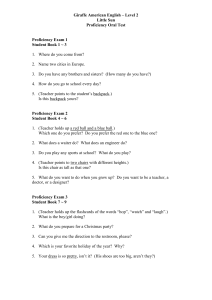

Language learning strategies and proficiency

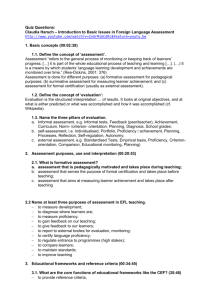

advertisement