Cultural Sensitivity and Diversity Awareness

advertisement

............

THE

SUMMER 1996

RESOURCE

CENTER

. VOLUME 6, NUMBER

3

NATIONAL ABANDONEDINFANTSASSISTANCERESOURCECENTER

Cultural Sensitivity and Diversity Awareness:

Bridging the Gap Between Families and Providers

-

-.;

-

Service providers across the United

States interact with children, families and

other professionals from an ever widening

variety of cultural, linguistic, and ethnic

backgrounds, suggesting a growing need

for cultural competency training. Many

staff deve]opment models that address

diversity emphasize the importance of

learning culturally specific information

including communication patterns, health

and illness beliefs and behaviors, religious

practices, symbols, and rituals (Stewart,

]991; Like, ]991; Nkongho, 1992). Generally, it has been assumed that knowing

about specific cultures and groups makes

it easier to respect and appreciate differences and to interact effectively with persons from other cultures. However, onehour presentations and occasional classes

do not adequately address the growing

need for cultural education (Pahnos, 1992;

Marvel, Grow & Morphew, ]993). The

challenge of understanding diversity and

becoming culturally competent does not

stop with learning the "do's and don'ts" of

a specific cultural group.

The authors of this article came

together as a team by participating in a

CRAFT* (Culturally Responsive and

Family Focused Training) program

designed for early childhood professionals

and parents of children with special needs.

This training made it clear that developing

cultural sensitivity and diversity awareness is extremely complex and an ongoing

process. The process begins with the

provider understanding his or her own

personal history and how it influences

his/her perceptions. Literature increasingly reflects the importance of family

structure, gender roles, and beliefs and

The third step involves the process

of finding common ground between the

provider's and the client's perceptions

which allows the provider to start an

appropriate and effective intervention.

Thus it is important that cultural awareness training programs offer insight into

how service providers can go beyond

the cultural chasm between their own

unique identity and the clients' distinctly

different identities. This article describes

a process that uses the Diversity Wheel

(a tool developed by the Oak]and CRAFT

team) to look at these three steps.

Diversity Wheel

F

values-not only as they relate to clients/

families, but also as factors that providers

bring to the encounter, and how this may

influence service delivery.

Second, the provider must begin the

process of understanding how similar

and/or different factors may influence the

perceptions of the client/family. This may

include, but is not limited to, becoming

more knowledgeable about specific cultural norms and practices.

rom childhood, we Jearn to look at

people's differences primarily through

cultural or facia] identities-e.g., this is

an Asian family, she is African American,

they are Italian. Each cultural/ethnic identification suggests a set of generalized

expectations covering religion, styJes of

communication, attitudes about family

relationships, and types of careers or businesses. Culture can include how people

live, role expectations, child rearing

practices, attitudes about time or money,

definitions of achievement, concepts of

beauty, art, music, food, and a host of

other things. Nonetheless, culture is only

one element of who a person is.

Please

seepage2

. Continuedframpage

Self Awareness

1

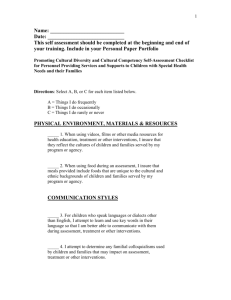

One way to help identify the myriad

factors which define an individual's

uniqueness is by using the Diversity

Wheel. This tool was developed to help

gain a better understanding of the many

factors which shape each unique individual. The Diversity Wheel (see Illustration

on p. 3) lists seventeen factors which may

influence values, behaviors, ideas, and

interpretations of situations. The user of

the Diversity Wheel can examine how

each of the sections on the Wheel pertains

to an individual. To use the Wheel effectively to gain self understanding (or understanding of the client), the provider

should, for each section of the wheel, ask:

What are my (or my client's) significant

experiences, beliefs and emotional attachments in this area? How do they affect

how I (my client) view the world and how

I (the client) interact with others? In what

ways might these experiences, beliefs, and

emotional attachments play an unconscious role in how I (the client) perceive

others? This is a process that a provider

needs to do thoroughly once and then

periodically as shelhe goes through significant life experiences and changes.

Some factors on the wheel (e.g.,

education and class status) may change at

different points in life as a person gets

older and has different life experiences.

Identified areas on the wheel at age 20,

for instance, may look different at age 50.

Some factors (e.g., gender and race) are

dimensions we are born with and cannot

easily change.

Given the many spokes on the Diversity Wheel, it would be limiting to see

either ourselves or others only through the

eyes of culture (one aspect of the wheel).

Other factors profoundly influence who

we are and contribute to our experiences

and perceptions of others. For example,

our socio-economic status not only influences our standard of living, but also the

neighborhood in which we live, our access

to health care and possibilities for future

planning. Although our cultural identity

may affect some of these, other factors,

like age, immigration status and primary

language, may also impact our experiences and world view.

AlA

RESOURCE

CENTER

Self perception plays a major role in our

ability to provide services. As providers of

service, particularly in diverse communities, it is critical that we have a clear

understanding of who we are as individuals. Experiences and life stories guide

interactions, expectations and biases. By

using the Diversity Wheel, we can begin

to identify our uniqueness and begin to

understand how we experience others.

With this process of self awareness, we

may identify personal beliefs underlying

our expected behaviors of others (PopeDavis, Prieto, Whitaker, & Pope-Davis,

1993). We each have individual reactions

based on our own histories and characteristics. Recognizing this, we can then begin

to see others for their unique qualities and

the diversity within their group.

to allow anyone person to represent a

particular cultural group, or to allow our

experiences with an individual to create

expectations of what the next experience

will be like. For instance, a provider met a

client who was a single parent released

from prison a few years ago and living on

welfare with an abusive boyfriend. The

provider expected that this would be a

high risk situation, since her experience

with ex-convicts had always been discouraging. In her experience, people who had

been in prison were not well educated, had

low self-esteem, and did not make use of

available resources. She had difficult

,..

'-

times establishing regular visits with these

clients, and often felt she was being

conned by them. The provider's doubts

about this parent proved to be false. Not

only did this parent complete her AA

degree, but she ended the abusive relationship, obtained a job, and maintained custody of her children.

Uniqueness of the Client or Family

Bridging the Gap

When

meeting with professionals,

clients bring with them their values and

ideas based on their personal histories.

Even though two individuals may share a

cultural identity, other factors may cause

them to respond differently to the same

situation. To illustrate this point, a member of our CRAFT team is a Jewish

woman from a small town in the eastern

United States. She had a friend who

attended the same elementary school,

worshipped at the same synagogue, and

whose family was from the same economic group. Their physical appearance was

similar, they wore similar clothes, and had

the same accents. The significant difference between these girls was that one was

from a family that was first generation in

the United States having survived World

War II in Europe. The other girl was second generation; her parents were born in

this country. This fact shaped how the

families of both of these girls responded to

many life decisions including trust in the

government, familial relationships, and

faith in future endeavors. In this instance,

invisible differences shaped and differentiated two girls who were otherwise very

similar.

In looking at what creates the uniqueness of individuals, it would be inaccurate

2

Bridging the gap between families and

providers starts with knowing what the

provider brings into the families' homesbeing aware of biases and agendas, and

being able to contain these issues while

remaining open for new perceptions. Biases form the basis for expectations, and

these expectations influence judgments

about families or clients. For example, the

most common child rearing task of feeding a baby is laden with cultural and individual values: dependence vs. independence, cleanliness vs. exploration, control

vs. choice. Someone who values independence may feel it is important to use feeding time as an opportunity for the child to

master the skill of feeding; wasted food

may not be a big issue. Self feeding may

be different for a family who is without

resources and does not have enough food

from month to month, or for a family who

is concerned about neatness or how much

food is consumed.

G

It is important to pay attention to

personal feelings, discomforts and uncertainties when working with families.

These discomforts can be indications that

the provider is in fact experiencing value

differences with the family. Not attending

VOLUME

6,

NUMBER

0)

3

.......

~

0

to these feelings may compromise the

quality of service and lose the familyfocused approach.

Part of forming a partnership with

families and working together is a dance,

learning when to lead, when to follow,

finding a rhythm, keeping in step. Sometimes toes get stepped on. Acknowledging

mistakes and learning to talk about them

with families is sometimes difficult for

professionals, but it is crucial if we are to

truly work together.

Bridging the gap is a complex process

that takes time. Do not be afraid to ask

questions. Many families may appreciate

the opportunity to talk about themselves.

Consider it a sign of progress when a family can engage in conversation about cultural and individual differences. It is critical, however, to not assume that there is a

clear understanding of each other because

the client has had a few discussions with

you.

Having a family focused approach is

crucial in supporting families and providing services. A tool like the Diversity

Wheel can help establish what is important to a family and why. If health care,

food or unpaid bills are a family priority,

it may be difficult for parents to attend to

their child's speech therapy needs. Even

when providing interventions specific to

the child, parents may be more concerned

about their child's ability to self feed or

entertain him/herself than in the ability to

do puzzles or have good transitional

movements. Knowing how to listen to

what parents feel they need involves

knowing what issues you as a provider

bring into their home.

ground between the values and priorities

of the family and of the provider. There is

always much to learn, and in that learning

mistakes will be made. The process outlined in this article is just a starting place.

The integration of these concepts into

provider/client interactions forms a basis

for culturally sensitive, family focused

service delivery.

-

Karen Tanner, M.A., Alfreda Turner

Ph.D., Susan Greenwald, L. c.S. W.,

Chela Rios Munoz, L. c.S. W,

Sonia Ricks

REFERENCES

Like, R. C, 1991. Culturally Sensitive Health Care

Recommendations

for Family Practice Training.

Family Medicine. 23(3),180-181.

Marvel, M.K., Grow, M., & Morphew, P., 1993. Integrating Family and Culture into Medicine: A Family

Systems Block Rotation. Family Medicine. 25(7),

441-442.

Nkongho, N.O., 1992. Teaching Health Professionals

Transcultural

6(3),29-33.

Pahnos, M.L, 1992. The Continuing Challenge of Multicultural Health Education. Journal of School Health.

62(1),24-26.

Pope-Davis, D.B., Prieto, LR., Whitaker, CM., & PopeDavis, S.A., 1993. Exploring Multicultural Competencies for Occupational Therapists: Implications for

Education and Training. The American Journal of

Occupational

* CRAFT is a training program administered

by

the Department of Special Education, Calij(,rnia

Concepts. Holistic Nursing Practice.

Therapy. 47(9), 838-844.

Stewart, B., 1991. A Staff Development Workshop on

Cultural Diversity. Journal of Nursing Staff Development. 2(4),190-194.

State University, Northridge

OiJlersity

Wheel

Conclusion

""

,

WOrking

successfully with clients/

families requires a family focused

approach which includes being culturally

sensitive and having a heightened awareness of diversity. Having culture specific

information is only a small part of

developing an alliance with clients and

families. Understanding the concept of

diversity is an ongoing, evolving process.

This process includes understanding

self, understanding the uniqueness of the

client/families, and finding a meeting

THE

SOURCE

Chela Rios Munoz, Oakland CRAFT Team

3

VOLUME

6,

NUMBER

3

The LIVE& LEARNModel ForCulturally

CompetentFamilyServices

Working

with families from diverse

cultural groups presents new challenges to

providers in community settings. Although

there are excellent materials and resources

available that deal with the theoretical and

technical aspects of family services, there

is very limited access to practical information and assistance in conducting successful interventions with families from

diverse cultural backgrounds.

Providers are often unaware of basic

principles of cross-cultural service delivery, including the definition and significance of culture as a factor in service

interactions, the dominant cultural values

common to specific populations, and the

ways in which the dominant Euro-American provider culture influences the delivery of services and the attitudes toward

clients.

For the purposes of this discussion, I

will define culture as a stable pattern of

beliefs, attitudes and behaviors, transmittedfrom generation to generation, for the

purpose of successfully adapting to other

group members and to the environment. In

using this definition of culture, we avoid

establishing hierarchies among diverse

cultures, and assume that all groups have

developed congruent approaches to issues

of social and environmental adaptation.

However, we can also infer that these

adaptations are group- and site-specific,

and that the relocation of persons adhering

to diverse cultures necessitates a long

period of re-adaptation to changing social

and physical environments. In this context, it is important to note that, due to the

history of the United States, and the relatively recent (the last 300 years) immigrant nature of the vast majority of its

population, there is-with the exception

of North American Indians residing in

ancestral lands-no perfectly adapted

cultural group at this time. This assertion,

of course, includes persons subscribing to

the dominant Euro-American culture. The

AlA

RESOURCE

CENTER

~)

.

United States, thus, is overwhelmingly a

nation of immigrants, and its entire population is currently seeking ways to adapt

socially and environmentally, regardless

of the fact that one particular cultural

group (Euro-Americans) is politically and

economically dominant.

Universality. The provider considers

that all humans share basic values and

therefore treats all people alike, regardless

of their differences. Since behaviors are

culture-bound, this approach results in a

standard intervention based on the cultural

Cross-Cultural Attitudes and

Client Reactions

.

Sensitivity. The provider acknowledges differences and tries to address them

by adopting external or formal cultural

expressions and presenting the standard

intervention within these parameters.

Cultural sensitivity usually is limited to

the use of the client's language and literacy level, and limited deference to major

taboos.

Whenever

a provider and a client from

different cultures meet, the former manifests a cultural attitude and the latter

exhibits some reaction. I will briefly

examine what these cultural attitudes are,

and how they may determine to a great

extent the reaction that the client exhibits.

I will use a model of cross-cultural attitudes and client reactions that range, on

the one hand, from superiority to cultural

competence, and on the other from resistance to adaptation.

Because in our society the provider

usually controls important aspects of the

service relationship, including site, environment, time of initiation, duration, and

type of intervention, the cross-cultural

attitude of the provider sets the tone for

the relationship. Possible cross-cultural

attitudes include:

.

Superiority. The provider considers

the client's culture inferior or worthless,

and actively tries to impose his/her values

and world-view. The intervention attempts

to effectively dismiss the client's values

and replace them as a pre-condition for a

service relationship.

.

Incapacity. The provider acknowledges differences, but has no skills or

tools to address them effectively, and

therefore proceeds with a standard intervention based on dominant cultural

values.

4

values of the provider.

.

Competence. The provider identifies,

respects, incorporates and maintains the

values of the client in the design, delivery

and evaluation of the service. The intervention is client-centered, as the provider

listens actively, elicits the client's worldview, acknowledges the differences and

similarities, recommends approaches congruent with the client's values, and negotiates their implementation or adaptation.

t)

Faced with one of these cultural attitudes, clients from a non-dominant culture

might exhibit one of the following reactions:

.

Resistance. Clients refuse to participate in the intervention, are unresponsive,

and may exhibit either hostility or passivity. In some cases, clients will purposely

minimize their understanding of the

provider's language.

.

Accommodation. Clients reject their

native culture and attempt to adopt the

values, attitudes and behaviors that they

perceive to be dominant. Clients will often

aim to please the provider and agree to

VOLUME

6,

NUMBER

3

~)

recommendations that are impractical or

inappropriate.

-.....

~

superficially "sensitive" as to border on

blatant stereotyping, clients often respond

with passive resistance. More commonly,

clients accept the "sensitive" more formal

aspects of the intervention, and reject the

core, which is based on dominant cultural

values. Cultural competence encourages

and accepts adaptation in clients, as it

openly recognizes and respects the differences and similarities in world-view,

while incorporating client values in the

serVIcecore.

TheLIVE& LEARNModel

I n the LIVE and LEARN Model, each

letter of the acronym stands for an attitude, strategy or activity that providers can

adopt to foster positive interactions with

their clients. This model has been culled

from the accumulated wisdom of diverse

sociologists, psychologists, social workers, interpreters, medical providers (most

notably P.S. Adler, H.A. Bulhan, R. Cashman, A. Castaneda, L. Comas-Diaz, G.

Marin, J. Pares-Avila, M. Ramirez and T.

Tafoya), and the practical experiences of

the staff of the Latino Health Institute of

Massachusetts, which serves more than

10,000 clients through approximately 40

different programs, most of which are

offered through its Family Services

Division.

c

L stands for Like. If the provider does

not have a genuine liking for diverse

families and their cultural origins, no

THE

SOURCE

attempt to transact personally meaningful business without the benefit of

interpreters. Another strategy is to

establish peer relationships with persons from other cultures, and thus gain

an insider's view of that culture

through the eyes and the minds of our

peers. In this context, we may consider

establishing such peer relationships

with colleagues and even former

clients from the cultures of interest.

reflect on our personal experiences, it

will become evident that we are seldom, if ever, competent at those

endeavors we dislike. For example,

children forced to take music lessons

against their will generally do not

become virtuosi; neither will providers

required to be culturally competent if

they lack the fundamental positive

predisposition for this work. It is far

more honest and productive to assess

whether diverse families would be

.

Adaptation. Clients maintain their

values, attitudes and behaviors, adapting

them to new circumstances, while simultaneously adopting skills and strategies that

allow them to function effectively in the

dominant culture.

Cultural superiority allows for either

resistance or accommodation, but largely

elicits the latter. Incapacity and universality often are met with resistance or accommodation as well, although these attitudes

do not actively lead to the obliteration of

the client's culture. Cultural sensitivity is

met by clients with the entire spectrum of

reaction. When the intervention is so

~

amount of skill development will

make an iota of difference. If we

better served by other providers.

I

is for Inquire. As a certain tabloid

constantly reminds us at supermarket

check-out counters, "inquiring minds

want to know." Providers that habitually work with certain populations

have a responsibility to familiarize

themselves with the demographics,

history, beliefs, traditions, social

norms, family structures, discipline

strategies, and preferred forms of

address of their clients.

"&"

L

stands for Listen. When we listen

attentively to our clients, we make a

special effort to discern not only the

content of their communication, but

the style which they employ. In the

dominant culture, this style tends to be

impersonal and to-the-point, focusing

more on verbal than on non-verbal

aspects. In many other cultures,

Continued on next page.

V is for Visit. When we perceive ourselves as guests in someone else's

home, we naturally adopt an attitude

conducive to observation, respect, and

emulation of our hosts' social norms.

Conversely, if we maintain a provider

attitude, even when conducting home

visits, we tend to bring to our relationships a clinical, business-like detachment that inhibits the process of observation and emulation of client norms.

Adopting the attitude of a visitor when

interacting with persons from other

cultures, especially when meeting with

them in our own offices, is a strategy

that allows us easier access into the

client's world.

E is for Experience. This letter suggests

two useful strategies. The first is to

consciously put ourselves in situations

in which our culture is not dominant,

such as attending social events at

which our language and mores have a

marked minority status. For example,

when traveling in a country in which

another language is dominant (and

English is not universally understood

or spoken), it is most instructive to

5

VOLUME

6,

NUMBER

3

. ContinuedfrOln

page 5

however, styles tend to personalize

communications by referring to experiences, interests and feelings, and

there is a greater focus on non-verbal

expression. Once we have discerned

the preferred communication style, it

wi]] not only be easier to understand

what is being said by clients, but we

will also know how to respond effectively by matching their style.

E is for Evaluate. Although not often

used in this sense, the verb to evaluate

litera]]y means "to determine the

value(s)." Because a]] clients integrate

culture and personality in markedly

individual ways, it is important to

determine the specific beliefs, attitudes and values to which they subscribe, thus avoiding stereotypes. It is

also important to elicit the level of

acculturation of clients, which is

often-but not always-associated

with length of residence in the United

States. Thus, within the same family,

individuals may hold beliefs and

values that are different, according to

generation or date of immigration.

Often, it is useful to ask open-ended

questions such as "How would your

grandmother have addressed this

issue?" Clients will then be at liberty

to state the values of the culture of

origin, and will volunteer valuable

information about their own proximity

or distance to/from those values.

A is for Acknowledge similarities and

differences. Once we have ascertained

the values of interest, it becomes necessary to clarify for the clients our

perception of the similarities and differences among values of the family

members, and between those and the

dominant culture. While identifying

cultural similarities is always useful in

establishing rapport, and is highly

advisable, it is equally necessary to

inform clients in a non-judgmental

manner of any differences, particularly

when those differences might eventua]]y arise in the service relationship. In

this regard, it is absolutely imperative

to inform clients if the legal require-

ments of our profession (i.e., mandated reporter) can lead us to use some

objective standards of behavior that

conflict with the stated client value

(i.e., harsh disciplining methods).

R is for Recommend. In addressing any

issue, there always are several possible

approaches, even though some may be

preferable to others. It is best to

describe for the client, while matching

their communication style, the entire

range of options and the consequences

associated with them. For this purpose,

we can i]]ustrate for the client several

approaches, from the least desirable to

the most desirable, and inquire from

them which approach seems to make

most sense, given their present situation and resources. This strategy wi]]

prevent us from recommending

impractical solutions, to which clients

may agree out of deference, but which

they have no intention, or insufficient

resources, to implement.

N is for Negotiate. Because, in most

cases, our interventions seek some

form of behavior modification, it is

important to reach an agreementpreferably in the form of a contractbetween the client and the provider as

to which option(s) will be put into

practice, what measures wi]] be jointly

used to monitor progress, and the

timeline for implementation. Should

the client agree to an option that is not

considered tota]]y appropriate by the

provider, negotiation might also

include a timeline for adoption of

more desirable options in the future.

Important Considerations When

Using the LIVE & LEARNModel

When

initiating work with persons

from diverse cultural orientations, standard assessment procedures should be

used in gathering data. Making assumptions solely on the basis of ethnicity is

both inaccurate and inappropriate. However, there are several critical areas that must

be explored in order to insure the gathering of a thorough psychosocial and developmental history that may result in accurate formulation and service planning.

In work with J. Pan-:s-Avila and our

co]]eagues at the Massachusetts General

Hospital, we have identified and discussed

certain critical considerations for engaging

clients in cross-cultural service relationships. Some of the most applicable are

noted below.

.nant Time.

Some persons with non-domicultural orientations have flexible

understandings of punctuality and aversion to a hurried pace, especia]]y within

the context of their expectation of close

social relations. Thus, emphasis on saving

time versus being cordial is viewed as

rudeness rather than efficiency.

.

Personal Space. Some persons with

non-dominant cultural orientations require

less personal space than those with EuroAmerican orientations. Additionally, some

persons with other cultural orientations

tend to touch more frequently, and handshaking, hugging, knee- and backslapping,

rib-nudging and cheek-kissing are frequently observed.

.

Country of Origin. A first consideration is the client's country of origin. In the

case of foreign-born persons with nondominant cultural orientations, it is important to explore the client's migration history. In the case of U.S.-born persons with

non-dominant cultural orientations, a similar migration history should be obtained

regarding the client's family, including a

determination of how many generations

ago the move occurred. Furthermore, the

provider should explore the client's experiences in the U.S. relative to discrimination and/or racism.

RESOURCE

CENTER

6

f)\i

.

Language Use and Dominance.

Assessment of language use and dominance is another critical area. When the

client with a non-dominant cultural orientation is seen by a monolingual dominantculture counselor and the client is fluent

in English, this is frequently overlooked.

When clients are not fluent in English,

providers often assume that they speak

only the language of their culture of origin. Language congruence is fundamental

to the effective delivery of services.

Among the approaches that can be used to

overcome language barriers, the most

Please see page 12

AlA

t

VOLUME

6,

NUMBER

.

3

t

EXCELLENCE

0

()

ACTION

The Effectiveness of Indigenous Recovering

Outreach Counselors in Reaching Substance Abusing

Women of Color Within the Drug Culture

There is growing consensus that a more

comprehensive and systematic approach is

needed to respond to the complex needs of

substance abusing women and their families. Drug addicted women come from

every social and economic class, race,

culture and religion. Virtually chained to

the close and perilous drug culture, victims typically look to other drug users for

the only social support they receive. They

rely on other addicts to guide them to safe

sellers, handouts, money and information

required to survive in the drug culture.

With rare exceptions, professional

outreach workers find it extremely difficult to gain acceptance from clients in the

drug culture. Ethnic and cultural influences on the client's life style, and clients'

interpretation of the environment, further

complicate the client/service provider

relationship. Drug addicted clients typically come from worlds significantly different from the ones that shaped the belief

systems of most professional service

providers. As a result, professionals often

have difficulty gaining credibility because

they lack an understanding of the drug

culture and the ethnic and cultural backgrounds frequently represented among

clients snared in this web.

The PEP Program

Q

IN

The PEP (Partnership to Empower

Parents) Program is an AlA project which

uses a consortium of consumers, community members, family care agencies,

educators, family preservationists and

substance abuse treatment specialists to

provide intensive outreach and concrete

services to help families in South Dade

County, FL, break the cycle of addiction

THE

SOURCE

and learn to parent their infants and young

children. To overcome the obstacles

described above, PEP selected and trained

some of the recovering clients, who had.

been drug-free for at least one year, to

serve as outreach workers for drug addicted women in targeted communities. With

these recovering clients, PEP created what

is called a DART Team (Drug Addiction

Recovery Team). Team members are

trained in assessment and in carrying out

their roles and responsibilities as paid peer

counselors and outreach workers to drug

addicted women in their own neighborhoods.

DARTTeam Members

PEP'S

DART Team members come

from the same neighborhoods and share

ethnic and cultural backgrounds with

program participants. Having grown up

and/or shared drugs with many PEP

clients, DART members are uniquely

positioned to develop a basic support system for clients' substance abuse recovery

efforts and family strengthening within the

context of their culture. They know the

environment, and they know what is going

on in the lives of their clients on a daily

basis. In those respects, DART team

members are more capable than "cultural

strangers" to communicate with the participants through speech and action. To start

where the clients are means understanding

the clients' culture first.

The shared cultural background of the

DART team and the client population

shifts the diagnosis and intervention activities from a pathological orientation to an

ecological orientation. The barriers associated with cross-cultural interactions (e.g.,

7

PEP: Healthy Baby

miscommunication, stereotyping and

narrow parameters of one's own cultural

background) are significantly reduced.

DART members can easily understand

situations in the context of history and

culture of the clients because it is their

own history and culture as well. DART

members can be considered "cultural

interpreters" for substance abusing women

of eolor.

As recovering substance abusers

themselves, DART workers are better able

to engage clients, explain the service

options in the client's language, recognize

clinical symptoms in a cultural context,

confront a client who claims to be off

drugs, and serve as guides to help participants traverse the sometimes culturally

insensitive family care treatment and

Continued on next page.

VOLUME

6,

NUMBER

3

. Continued from page 7

service systems. For example, the importance of the simple request by an AfricanAmerican client to "have her hair done"

before entering a residential treatment

center is understood and facilitated by

DART members. The request is culturally

significant and, once given the attention

needed, is removed as a barrier to the

recovery process.

DART team members also serve as

role models for clients. They are seen as

"scouts" who travel successfully outside

of the neighborhood, bringing their clients

information, ideas and resources necessary

to assist clients in the recovery process.

They stimulate participant interest in substance abuse rehabilitation and drug-free

life styles. Through models set by team

members, client participants begin to feel

that they, too, can achieve sobriety and

learn life management skills similar to

those exhibited by the recovering "sisters"

on the DART team. The following case

example illustrates the valuable contributions of indigenous counselors.

t

PEP Community Board Training

drug-using companion convinced her that

maybe there was hope for her.

With the help of the DART team,

Staci entered a residential treatment center

and reconnected with drug-free extended

family members. She is working toward

reunification with her children, and plans

to become a DART member in the future.

Staci, a PEPClient

DARTMembers as Team Players

Staci came to the PEP program in 1995,

addicted to both alcohol and crack. From

1988-1995, Staci exchanged sex for money or drugs to support her habits. Staci

reported being in jail for one year on an

assault and battery charge that she says

was directly related to her addictions.

Staci has six children, three of whom

were prenatally exposed to drugs and

alcohol. She is currently receiving AFDC,

food stamps, Medicaid and Section 8

Housing. She is unemployed and has been

for 15 years due to her alcoholism and

drug addictions.

Staci says that she needed the DART

team members to help her realize that she

could actually get clean and sober and stay

that way. This message was conveyed in

an experiential manner; she knew one of

the DART members because she had

used drugs with her in the past. Staci says

that this same woman came to her house

and became an example to her, and that

the transformation she saw in her former

D ART members

are also a critical

source of information for the community

and professionals who work with PEP

clients. As recovering addicts, DART

members serve as communicators to community organizations regarding substance

abuse among women, and they provide the

community with information about services available from PEP to help mothers

overcome substance abuse and its effects

on their children and families. The DART

team distributes information and

brochures, and reaches out to mothers and

their children in need of help to overcome

drug abuse.

Additionally, DART members provide PEP's professional staff, and other

community providers, with critical information on the ethnic and cultural beliefs,

values and practices of their clients, and

help professionals to understand behaviors

which are characteristic of the drug culture. DART team members are included

in regularly scheduled staff meetings with

PEP's professional social workers to

review and discuss clients and their treatment plans. DART members provide

information about clients from a different

cultural perspective, and offer their interpretation and assessment of clients'

behavior. The entire staff works together,

respecting and integrating the perspectives

and assessments of both professional and

peer workers, to develop and revise client

intervention plans.

This is not an easy process. Along

with the undeniable benefits of using peer

workers, there are always challenges to

managing a staff which is culturally, ethnically, economically and educationally

diverse. DART team members often need

t)11

support in their own recovery process, and

assistance drawing the line between client

and peer/friend. Despite these challenges,

PEP attributes much of its success in

reaching substance using women of color

to the culturally competent work of the

DART team-peer workers who share the

clients' ethnic, racial and socioeconomic

background and who have experienced the

drug culture first-hand.

-

Shirley Pinder Cook &

Scott Briar, DSW

tl

AlA

RESOURCE

CENTER

8

VOLUME

6,

NUMBER

3

Culturally Competent Program Evaluation

rO

It

I n recent years, family support programs

have increasingly recognized the importance of cultural competency in providing

services tofamilies with children affected

by substance abuse and HIV. However,

cultural competence principles are just

beginning to be considered in the evaluation (~fprograms and systems which serve

these families. Andres Pumariega (1996)

points out that "the cultural 'blindness'

approach which has characterized the

field of evaluation has kept [evaluators}

from identifying important differences in

needs and orientation to service utilization

across ethnic groups" (p. 1). In order to

make programs more effective in reaching

and improving outcomes offamilies with

different cultural, racial and socioeconomic backgrounds, process and outcome

evaluations must consider and reflect

cross-cultural differences. Thefollowing

information, excerptedfrom Pumariega

(1996)*, offers practical guidelinesfor

designing culturally competent evaluations.

Defining Program Characteristics

An evaluation for either a program or a

system of care begins with defining consumer/population, process, and outcome

characteristics. This gives the evaluation

the data it needs to answer the key questions of which interventions work, for

whom, and how.

Consumer/population characteristics

include information about race and ethnic-

,

ity as well as other demographic characteristics that often interact with culture, e.g.,

gender, age, socioeconomic status, and

urbanicity. Relating these characteristics

to the geographic region being served

sheds light on factors that influence service delivery, e.g., the proximity of the

population to natural stressors and physical access to services. If there are significant culturally diverse populations, it is

useful to know how the target populations

compare to the prevailing community

population.

Program characteristics are also key

in designing an evaluation. The philosophy of the program or system determines

the service model and the associated

process characteristics to be examined.

Process characteristics can include type

and frequency of interventions, length of

stay, attainment of individual treatment

goals in care plans, staff involved in interventions, and behaviors that change as a

result of applying interventions. Culturally

relevant process questions include:

. What outcomes are expected from the

program and how do they compare to the

functional expectations of individuals of

the cultures/ethnicities/socioeconomic

status being served? (For example, if

emotional separation and autonomy is an

important program outcome, is this appropriate for a cultural group for which multigenerational closeness is the norm?)

. How does program philosophy relate to

staffing composition, including the distribution of professional disciplines and their

ethnic composition?

. How does the program relate to the

community organizations/leadership that

represent minority groups served?

(Windle, Jacobs & Sherman, 1986)

. Is effective cultural competence training available for statl and how does it

impact program philosophy?

. How does program philosophy compare and interact with the cultural values

of the target population, e.g., emphasis on

spirituality, individual versus family orientation, and assignment of clients to

different therapeutic modalities? This may

include traditional healing approaches

(religious ceremonies, rituals, specific

cultural interventions such as sweat

lodges, or community intervention), and

which clients benefit from such interventions as opposed to Western approaches.

. What are the points of entry into the

program and the barriers to accessing

care? How do those relate to the clients'

cultural and socioeconomic needs?

Outcome characteristics in evaluation

usually involve symptom change, functional change, safety, cost, community

tenure and level ofrestrictiveness, and

consumer/family burden and satisfaction.

Culturally related outcome questions

include:

. How do outcomes differ across cultural, racial or ethnic groups?

Participation

by the Community

and Providers/Agencies

Staff, child, and family participation

must be fostered in order to evaluate a

program or system of care. Minority community members often are not enthusiastic

about evaluation because of prior negative

experiences. There is also mistrust about

whether research will be used as a tool of

government agencies, immigration, social

services/child welfare agencies for custody termination or termination of benefits. Research methodology sometimes

conflicts with cultural values, tradition,

and accepted means of communication of

sensitive information. Staff may fear that

evaluation might frighten families away

from services.

A number of approaches can be used

to engage the cooperation of minority

children and families. Seeking out advice,

input, and endorsement from leaders and

elders in the minority community is quite

effective, both in building trust and in

Continued on next page.

THE

SOURCE

9

VOLUME

6,

NUMBER

3

. Continued from page 9

informing the selection of instruments,

methods, and procedures. Recruiting

evaluation assistants from the community

builds in community involvement and

expertise. Cultural competence training

for staff as outcome evaluation is introduced can heighten awareness for the need

to examine cultural diversity issues.

Informed consent procedures must also

be easily understood and should involve

appropriate family members indicated.

share many life experiences in common,

and may be hard to generalize to other

groups.

Sampling from culturally diverse

groups must assure that the racial/ethnic,

socioeconomic, age, and gender composition of any sample reflects the service

population. Oversampling or stratification

of samples may be necessary if the samples of culturally diverse individuals are

too few in number to be representative.

Measurement Strategies

Evaluation Design and Sampling

Selection of instruments and measurement strategies introduces many cultural

considerations. Few instruments are

The nature of the actual design

chosen has significant implications for

culturally diverse groups.

appropriate for use across different cultural groups, and some have subtle but distinct cross-cultural biases (Pumariega,

Holzer & Swanson, 1991). Instruments

being used or compared across cultural

groups should have these characteristics:

. Pre-post or multiple baseline designs

are commonly used. However, culturally

diverse populations served frequently

change over time for reasons other than

interventions provided, e.g., exposure to

mainstream culture, generational change,

and signal events in the life of the community (Szapocznik, Scopetta & King, 1978).

It is important to monitor such intervening

changes when using these designs.

. Single case methodology, which tracks

ratings of selected target behaviors before

and after intervention to determine effects,

is useful in evaluations involving groups

which have only small numbers of people

available.

. Experimental designs, where clients are

randomly assigned to different interventions, are often consider the "gold standard" scientifically. However, these studies are hard to implement in the real world

of service provision. Ethical questions

may come up when one group is receiving

an intervention that is obviously less

worthwhile, and this reinforces suspicions

in ethnic minority clients.

. Longitudinal designs following a

cohort of clients over time to measure

outcome can be useful. Their drawback is

that some behavioral changes may be

specific to certain "cohort" groups if they

AlA RESOURCE

CENTER

. Conceptual equivalence: the same theoretical construct is being measured across

different cultures (e.g., parental role function is defined the same in all the groups

being studied).

. Semantic equivalence: both translation

across language as well as idioms and

expressions of the groups being studied

are accounted for (e.g., the Anglo term

feeling "blue" does not have meaning for

Hispanics, and has a historical context for

African-Americans).

. Content equivalence: the content of

each item in the instrument is relevant to

the phenomenon being studied in that

culture. For example, the concept of being

"put-upon" may not have an equivalent

expression in another culture. Lack of

familiarity with clinical jargon and different understanding of symptoms and culturally-bound syndromes (e.g., schizophrenia versus being possessed) must be

taken into account. It may be necessary to

include descriptors of illness or behaviors

in questions.

. Criterion equivalence: the variable

measured is interpreted based on the

norms for that culture (e.g., the level of

depression and the cut-off for significant

10

depression is based on the normative

response for that culture). Measures of

symptoms or behaviors need to account

for culturally determined thresholds of

dysfunction within the community. It may

be necessary to develop different cut-off

scores for different ethnic groups using

culturally-specific normative samples.

~I

. Methodological equivalence: methods

of assessment and data collection yield

comparable responses across culture. For

example, it is a problem if some groups

are more open in self-administered questionnaires, while others prefer interaction

with,an interviewer.

A problem which periodically arises

is whether to use instruments specific to

one culture or cross-cultural instruments.

Mono-cultural instruments may be necessary when specific aspects of a culture are

being evaluated as a variable in the impact

of a program, e.g., ethnic pride/ethnic

identification in a particular culture.

Instruments that can measure constructs

across cultures are necessary when making comparisons across cultural/ethnic

groups. It may be necessary to develop

parallel versions of instruments that are

specific for different groups.

Qualitative approaches, e.g., openended questions, interviews, or observations, may be useful in eliciting important

perceptions or attitudes without the limits

imposed by rating instruments. These

approaches often are very compatible with

cultural values and means of transmission

of information in communities.

The measurement of cultural identifi-

tJ

cation and cultural value orientation presents particular challenges. The construct

most commonly endorsed in the crosscultural mental health field is that of

biculturality or multiculturality, i.e., culturally diverse individuals by necessity are

bi-cultural or multi-cultural in order to

adapt successfully. The domain of cultural/ethnic identification must allow for this

construct, and must take into account a

number of domains, e.g., self-identification, relational patterns (friends, intimate

relations, etc.), culturally related traditions

and preferences (clothing, foods, traditions, language, media, etc.), and cultural

value orientation. For many children and

VOLUME

6,

NUMBER

3

{I

(0

families, the measure of concrete behaviors or activity orientations are a valuable

means of assessing cultural identification.

These include simple activities such as the

amount of time spent with family, religious activity, and time spent exposed to

the media (Pumariega, et aI., 1992).

Use of Databases and

particular cultural populations. The imperatives for cost effectiveness and clinical

effectiveness which have been promoted

by the transition to managed systems of

care may actually promote the development of higher levels of cultural competence in community-based systems of

care. Culturally competent care may well

be the most cost-effective and clinicallyeffective care.

Behavioral

Symptomatology.

of the

Pumariega, A., Swanson, J., Holzer, c., Linskey, A. &

Quintero-Salinas, R. (1992). Cultural Context and

Substance Abuse iu Hispanic Adolescents.

of Child and Family Studies, 1(1): 75-92.

Szapocznik,

Journal

1., Scopetta, M., & King, O. (1978). Theory

and practice in matching treatment to the specific

characteristics and problems of Cuban immigrants.

Journal of Community Psychology, 6, 112-122.

Windle, c., Jacobs, J.H. & Shennan, P.S. (1986). Mental

Health Program Performance Measurement,

Rockville, MD: ADAMHA,

Clinical Records

Proceedings

Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child

& Adolescent Psychiatry. Volume VB, NR-1l9.

NIMH, Division of

Biometry and Applied Sciences.

REFERENCES

Kilgus, M., Pumariega, A. & Cuffe, S. (1995). Race and

Clinical or agency databases may be

important information sources for outcome evaluation. However, there are often

problems with the rating of ethnic/racial

identification in databases. Often clini-

(t

cians do not ask race/ethnicity directly,

but infer it from appearance or surnames!

Problems often occur with the coding

categories used for cultural and ethnic

groups, with insufficient or unclear categories (e.g., a single Hispanic category or

Asian/Pacific Islander combined). There

are also problems with the coding of

much culturally-related information in

databases, such as socioeconomic status,

diagnosis, and service utilization information. It may be important to develop

rational coding categories for clinical

database information, with instruction for

clinical staff or other staff entering information. Racial/ethnic bias in clinical diagnosis is well documented, especially by

clinicians not familiar with the culture

(Kilgus, Pumariega, & Cuff, 1995), so that

these data might have limited utility. It

may be more valuable to have clinicians

rating the presence of symptoms reported

by the base of objectivity and not contaminated by the biases of classification systems.

Diagnosis in Adolescent Psychiatric

Inpatients.

Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent

Psychiatry. 34(1): 67-72.

Pumariega,

AJ. (1996). Culturally Competent

Evaluation

of Outcomes in Systems of Care for Children!s

Mental Health. TABrief, 2(2): 1,3-5*

Pumariega, A., Holzer, c., & Swansou, J. (1991).

Cross-Ethnic

Comparisou

*TABrielis

a newsletter published by the

Technical Assistance Centerfor

the Evaluation of

Children's Mental Health Systems, located at

Judge Baker Children's Center, 295 Longwood

Ave., Boston, MA 02115. Ph (617) 232-8390,

x2139; Fax (617) 232-4125.

of Youth Self Report of

Conclusion

f

The practice of culturally competent

outcome evaluation needs to be greatly

developed given the culturally diverse

nation in which we live and the different

needs of culturally diverse children and

their families. Such evaluation is crucial

in supporting the need for an effectiveness

of culturally competent programs and

for special programs with a focus on

THE

SOURCE

11

VOLUME

6,

NUMBER

3

. Continued from page 6

appropriate, in descending order of effectiveness are: (1) providing the service with

bilinguallbicultural staff; (2) using trained

interpreters (simultaneous or consecutive)

and providing effective training to interpreters and service providers in the preferable modes of interpretation, team building, and communication strategies; and (3)

teaching monocultural providers the

language(s) of the clients.

Providers should determine whether

clients are English-dominant, language of

origin-dominant, or bilingual. Even for

English-dominant clients, it is important

to assess what language is spoken at home

and what type of schooling the clients had

(bilingual or English-only programs).

Providers should be aware that original

language-dominant or bilingual clients

speaking English may invest more energy

in correct expression, thus giving precedence to the cognitive aspect of communication over the affective component of

language. Thus, these clients may appear

more constricted or flat.

Clients may also use bilingualism as a

defensive structure, utilizing one language

to communicate and reserving another as

the emotional language. Clients may discuss certain emotionally charged topics in

their non-dominant language as a way of

gaining some emotional distance. At other

times, clients may use their dominant

language in order to access meaningful

memories or experiences. Even if the

provider is monolingual, it is useful to

allow clients to think out loud in their

dominant/emotional language to facilitate

their access to and organization of meaningful material.

.

Natural Support Systems. Another

area to consider is the client's natural

support systems. The availability of such

support will be crucial in helping clients to

cope with their family issues. An assessment of the social network should include

a list of friends and acquaintances indicating their ethnic background. The current

state of relationships with the extended

family is particularly important. In this

regard, both family meetings and genograms are useful assessment and intervention techniques that should be considered.

AlA

RESOURCE

CENTER

When it is not possible to interview the

family due to geographic and/or emotional

distance, use of a genogram is highly recommended in gaining an understanding

of family dynamics and relations. The

provider should also establish whether the

client has attributed family status to nonblood-related individuals, as this is frequently done by persons with non-dominant cultural orientations. If such is the

case, the provider should treat these family members accordingly, and include

them in the assessment and intervention

process. Gathering a history of intimate

relationships is also crucial. If the client

(parent) is currently in a relationship, it is

important to explore whether the partner

is from the same or a different cultural

group. If the partner is not from the same

cultural group, the provider should assess

how the couple deals with their cultural

differences, and how these differences

affect the couple's and the family's

dynamics.

.

Provider Selection and Transference Issues. The social network data will

provide useful information that may help

in anticipating potential transference

issues that may emerge in a service relationship. How the client deals with racism,

ethnocentrism, and other issues may be

seen in the client's interpersonal relations

and choice of friends and partners.

This will also become apparent in the

client's selection of a provider, when a

choice is available. Given the scarcity of

providers from matching cultural origins,

for example, clients will most likely be

forced to choose according to age, gender,

or language fluency. Some will give priority to language, while others will favor

gender or age. Still others may choose

providers with considerable expertise in

the area of their basic presenting issue or

problem, regardless of ethnic background.

This forced choice should be explored in

the assessment process, as it may illustrate

meaningful psychosocial information. It

will also have significant intervention

implications.

When the selection results in a culturally discordant service relationship, the

dynamics that occur in the client's social

network will be played out in the intervention. Then, more than ever, providers must

12

be aware of and sensitive to the power of

differentials that exist between them and

their clients.

.

Other Considerations. It is always

important to consider specific values,

attitudes, norms, and expectations in

designing service plans. For example,

providers should be aware that reliance on

Euro-American relationship models where

women are assertive and independent

might be uncomfortable and culturally

inappropriate for other women. Most

importantly, interventions should assist all

women in translating knowledge and

awareness of coping skills into successful

verbal and behavioral repertoires. For

some women the emphasis may lie more

with nonverbal than verbal skills.

Possible negative impacts on the family, especially on children, may increase

the motivation of more traditionally-oriented men and women to accept service.

Male-dominant traditions may provide

useful intervention strategies with men

because cultural values emphasizes their

role in assuming responsibility for and

protection of the family. Finally, if at all

possible, providers should offer clients a

choice of either or both English and their

preferred language. If providers have

limited command of other languages, they

should avoid literal translations. Monocul-

f)

~

turallbilingual providers also should avoid

regionalisms in language and consider the

educational level and socioeconomic status of clients in their choice of words,

images, and metaphors.

The LIVE & LEARN Model presents

providers with a practical, phased

approach to cross-cultural service delivery

that respects client centrality, avoids

stereotyping, and leads to the adoption of

mutually acceptable objectives-and measures-for behavior change. It is simple

and straightforward, and accommodates

varying degrees of provider cross-cultural

experience, always leaving room for

improvement.

-

Nicolas Carhalleira, ND, MPH, DSc

Latino Health Institute of

Massachusetts

~)

VOLUME

6,

NUMBER

3

AlA Resource Center

The Source

1950 Addison St., Ste. 104

Berkeley, CA 94704-1182

Tel: (510) 643-8390

Fa:c: (510) 643-7019

Production

Betsy Joyce

Principal Investigator

Richard Barth, Ph.D.

Director

Jeanne Pietrzak, M.S.W.

Senior Research

Associate

Amy Price, M.P.A., B.S.W.

Research

B.A.

Staff Researcher

Research

Contributing Writers

Scott Briar, Nicolas Carballeira,

Shirley Pinder Cook,

Susan Greenwald, Chela Rios Munoz,

Ruth Pontifiet, Sonia Ricks,

Karen Tanner, Alfreda Turner

Associate

Gwen Edgar-Miles,

Sheryl Goldberg,

"

Editor

AmyPrice

M.S.W., Ph.D.

Assistants

Ruth Pontitlet, B.A.

Carmen Hernandez, B.A.

Megan Vogel-Edwards,

B.A.

Leslie Zeitler, B.A.

Support Staff

Renee Robinson, B.A.

The Source is published by the

AlA National Resource Center

through grants from the U.S.

DHHS/ACF Children's Bureau

(#90-CB-O036). The contents of

this publication do not necessarily

reflect the views or policies of the

Center or its funders. nor does

mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations

imply endorsement. Readers are

encouraged to copy and share

articles and information from The

Source, but please credit the AlA

Resource Center. The Source is

printed on recycled paper.

"...

,-P

AbandonedInlants Assistance

RESOURCE

University of California, Berkeley

School of Social Welfare

AlA Resource Center

1950 Addison Street, Suite 104

Berkeley, CA 94704-1182

(510) 643-8390

Nonprofit Org.

U.S. Postage

PAl D

Berkeley, CA

Permit No.1

CENTER

Address Correction Requested

r

,I