Wikilaw: Securing the Leaks in the Application of First Amendment

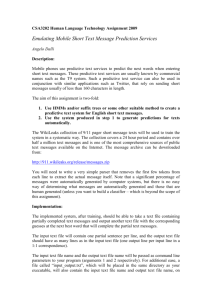

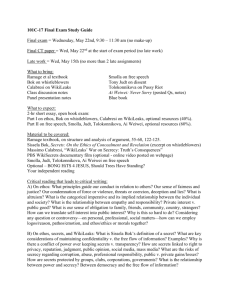

advertisement