- IREP - International Islamic University Malaysia

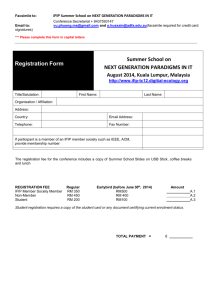

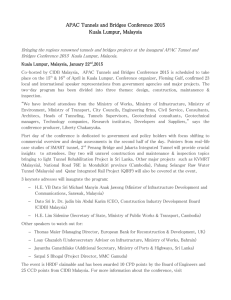

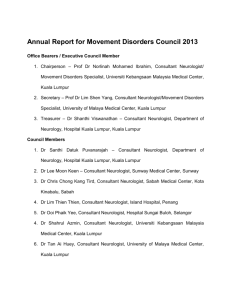

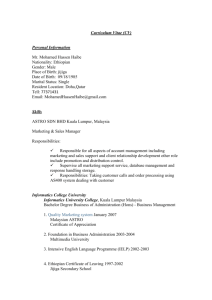

advertisement