The Reincarnation of Barter Trade as a Marketing Tool

advertisement

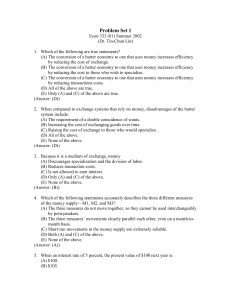

Jack G. Kaikati The Reincarnation of Barter Trade as a Marketing Tool Barter trade has become one of the most rapidly growing tools of international and domestic marketing. T HE great economist Adam Smith criticized barter trade as a primitive, crude, and unrefined system of exchange. Yet in 1976, two hundred years after Smith wrote his Wealth of Nations, barter has become one of the most rapidly growing tools of international and domestic marketing. It is no longer being used solely by the Communist bloc and the developing nations, but is now employed by the sophisticated marketers of the West as well. The new barter business is centered in the old cities of London and Vienna as well as the trading ports of Hamburg and Rotterdam. These cities now serve not only as the entrepots for the landlocked countries of Eastern Europe, but also as exchanges for the surplus commodity exports of the developing world. Moreover, in the U.S. domestic market a great deal more barter trading is being done now than ever before. This article attempts to explain the basis of the current revival of barter in modem business and to provide background information for executives contemplating the possibilities of barter. First, the major economic, political, and cultural factors that currently favor barter trade on an international level are examined. Then, the major types of international barter transactions currently being negotiated regularly are categorized, and the challenges facing Western managers contemplating such deals are discussed. Finally, a similar classification scheme is applied to domestic barter, and the author points out some of the legal and tax implications of these domestic barter transactions. Factors Favoring International Barter Trade At least four prevailing factors have led to the increase in international barter trade: (1) the expansion of East-West trade, (2) the importance of barter trade in developing nations, (3) the energy crisis, and (4) the evermounting inflation and worldwide recession. The Expansion of East-West Trade The policy ot East-West detente has facilitated the relaxation of unilateral Western trade barriers and has encouraged more "cooperative agreements" between East and West. The current interest in East-West trade has resulted in a plethora of articles dealing with marketing in the Communist world. These articles were written by professional academicians' and business executives^ who had frequent contact with the Eastern 1. See, for example. Gabor Hovanyi, "Marketing Strategy in Socialist Industrial Enterprise," European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 6 (Spring 1972), pp. 42-52; G. Peter Lauter, "The Changing Role of Marketing in Eastern European Socialist Economies," JOURNAL OF MARKETING. Vol. 35 (October 1971), pp. 16-20; A. Coskun Samli, "A Comparative Analysis of Marketing in Romania and Yugoslavia," Southem Journal of Business, Vol. 5 (July 1970), pp. 108-113; and David B. Zenoff and Donald L. Cuneo, "Formulating Strategy for U.S. Business with Eastern Europe," Financial Analyst Journal, Vol. 27 (July-August 1971), pp. 67-80, 91-94. 2. See, for example, J. H. Giffen, "Developing a Marketing Program for the USSR," Columbia Journal of World Business. Vol. 8 (Winter 1973), pp. 61-68; Clyde D. Hartz, "A Business Trip to Eastern Europe: Buying, Selling and Journal of Marketing, Vol. 40 (April 1976), pp. 17-24. 17 18 Journal of Marketing, April 1976 TABLE 1 U.S. EXPORTS TO EASTERN EUROPE, U.S.S.R., AND CHINA ACTUAL FOR 1971-1975 AND PROJECTED FOR 1978 (In millions of current dollars) Projected Exports' Actual Exports Trade Partner 1971 1972 Eastern Europe 221 268 606 820 480 U.S.S.R." 161 484 1,187 612 525 China — 63 1973 689 1974 820 Estimate 148 High Middle Low High Middle Low N/A 1978 If Trade Is "Maintained" 1978 If Trade Is "Normalized" 607 465 356 357 1,550 1,239 888 1,051 232 N/A 684 N/A ' First six months only. " Actual includes grain. ' The procedure underlying the forecasts is: (1) to exclude the abnormal 1972-73 grain deal, which explains why the forecasts seem low in comparison to actual 1972-73 U.S. exports to the U.S.S.R.; (2) to present two principal variants: with and without relaxation of discriminatory controls and, within each variant, high, middle, and low estimates representing the fitting of different curves to different time periods; and (3) to make the assumption that the "normalized" U.S. share of manufactured goods imported by EE and Russia would have the same competitive position in EE and Russian markets as in Western markets. "Normalization" includes abolition of all U.S. export controls that are more severe than those of principal competitors as well as the limitations on Export-Import Bank credit guarantees. Sources: (1) Actual (1971-75): U.S. Department of Commerce, The United States Role in East-West Trade: Problems and Prospects (Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office, August 1975); (2) Projected 1978: Erast Borrisoff and Stephen Sind, "Projections of U.S. Exports to USSR and Eastern Europe," Research Note 3, Analysis Division, Bureau of East-West Trade, U.S. Department of Commerce, May 1973. bloc. Some of these articles stress the importance of barter trade when dealing with the Communist countries. U.S. exports to the Communist bloc have grown at an impressive rate over the past few years. Table 1 provides a breakdown of U.S. exports to Eastern Europe, Russia, and China. By far the most important factor explaining the explosive growth of U.S. exports to Russia in 1972 and 1973 was the first wheat deal. By 1974, there was a 50% decline in U.S. shipments to the Soviet Union due primarily to the phasing out of grain exports. However, the second wheat deal, which firmly commits the Soviets to buy at least six million tons of U.S. wheat and corn annually over the next five years, will certainly improve U.S. exports to Russia. Moreover, the U.S. Department of Licensing," Business Economics, Vol. 9 (May 1974), pp. 39-45; Clyde D. Hartz, "A Business Trip to Eastern Europe: Joint Ventures and Practical Lessons," Business Economics, Vol. 9 (September 1974), pp. 34-44, and E. J. Milosch, "Imaginative Marketing in Eastern Europe." Columbia Journal of World Business, Vol. » (Winter 1973), pp. 69-72. • ABOUT THE AUTHOR. Jack G. Kaikati is a doctoral candidate in marketing in the College of Business, Florida State University, Tallahassee. Commerce estimated that in 1975 there would be a further strengthening in the relative share going to manufactured exports.^ Table 1 also presents projections of U.S. exports to the U.S.S.R. and Eastern Europe, which were made by two experts on the staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce's Bureau of East-West Trade. As a rough approximation, U.S. exports to Eastern Europe could double in five years from the relatively high 1973 level of $606 million to about $1.2 billion in 1978, according to the "normalized" middle-level forecast." Contrary to the above rosy forecasts, however, recent trade relations between the U.S. and the Soviet Union are not as firm and mutually satisfying as they were before Congress imposed some restrictions late in 1974 via the Trade Reform Act and the Export-Import Bank (Eximbank) Extension Bills. Specifically, the Russians objected to: (1) the Congressional demand that the Soviets should adopt a liberalized emigration policy— 3. 'World Trade Outlook tor Eastern Europe, Union of Soviet Socialist Republic and People s Republic of China," Overseas Business Reports, U.S. Department of Commerce, March 1975, p. 6. 4. Erast Borrisoff and Stephen Sind, "Projections of U.S. Exports to U S S R , and Eastern Europe," Research Note 3, Analysis Division, Bureau of East-West Trade, U.S. Department of Commerce, May 1973. 19 The Reincarnation of Barter Trade mainly for Jewish people—in order to get "mostfavored-nation" tariff treatment from the U.S.; and (2) a House-Senate limit of $300 million on credits from the Eximbank over a four-year period. The Soviet Union considers the restrictions to be unacceptable meddling on the part of the U.S. Congress into its internal affairs and so has abrogated the 1972 trade expansion agreement with the U.S. In spite of the rupture in the trade pact, the U.S.-U.S.S.R. Trade and Economic Council is optimistic about the Ford administration's effort to formulate new legislation that is more favorable to a renewal of trade with Russia.^ The Importance of Barter Trade in Oeveioping Nations For most developing countries, barter trade holds several potential advantages. First, for a country like Sudan, which relies heavily on the unstable cotton market to provide the wherewithal for purchasing capital goods, barter trade permits a certain degree of planning. A second advantage is that barter may be used by developing countries as a source of financial aid. For example, the clearing agreement between Ghana and the U.S.S.R. provided that either side might accumulate an import or export surplus of four million Ghanian pounds before remedial action needed to be taken.^ Thus, the agreement provided Ghana with an opportunity to obtain four million Ghanian pounds worth of Soviet goods at minimal cost. Also, bilateral trade does not involve the use of scarce foreign exchange. The lack of hard convertible currency needed to acquire capital goods tends to compel these developing countries to rely more heavily on barter trade. For example, a recent survey of Pakistani commerce showed that 60% of its trade with Eastern Europe had been in barter deals, which increased four-fold in the 1960s, with Pakistan swapping shoes, cotton, and jute for industrial machinery from Russia and its satellite countries.' The Energy Crisis The current energy crisis has also had a favorable impact on barter trade. The crisis has added a great deal of respectability to bilateral barter deals. Public announcements indicate that Westem and Japanese governments have promised to 5. "U.S.-U.S.S.R. Council Optimistic on Trade," Industry Week, February 3, 1975, pp. 20-21. 6. Ghana Treaty Series (Accra, 1961), No. 57. 7. Michael Kidron, Pakistan s Trade with Eastern Bloc Countries (New York: Praeger, 1972). provide the oil-producing nations with everything from refineries and chemical plants to arms in return for guaranteed supplies of oil. Typical is the French agreement to barter a long list of industrial products, hydroelectric power stations, and defense equipment in return for a guaranteed supply of Iraqi oil. Britain negotiated a smeiller deal to swap $242 million worth of industrial equipment for 100,000 barrels per day of lowerpriced Iranian oil during 1975. Numerous other barter deals of this nature have been conducted during the last year, and the tempo gives every indication of increasing.* The international oil companies, however, show signs of reluctance to further extend barter trade in exchange for oil supplies. The oil companies apparently fear that bilateral barter deals at artificially high prices will make negotiating longterm agreements difficult, because the oil-producing countries will probably use the high price of the barter deal as a bargaining counter. The Current Worldwide Inflation and Recession In addition to the devastating energy crisis, worldwide inflation and recession have also boosted barter trade. Historically, barter trade usually reappears during periods of economic distress.^ For example, the depletion of most trading nations' foreign trade reserves after World War I led to an upsurge of barter trade in the 1920s. Barter trade which started in Europe during the Great Depression had spread throughout the world prior to the Second World War. Following World War 11, it reappeared due to the paucity of foreign e.xchange. Since then, most of the world, except Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and mainland China, has moved away from barter trade. Now a barter system is reemerging in the Western world as a result of the disturbing economic conditions of rampant inflation, persistent recession, chronic balance of payments deficits, and widespread shortages of raw materials. Perhaps it is this long-time association of barter trade with chaotic economic conditions that caused the U.S. secretary of state to condemn oil 8. "France: Government-to-Govemment Deals," The Petroleum Economist, Vol. 41 (January 1974), p. 12; "Scramble to Make Barter Deals," The Petroleum Economist, Vol. 41 (February 1974), p. 51; "Trade: A Payments Deficit Haunts Oil Consumers," Business Week, February 9, 1974, p. 37; "France Goes It Alone," The Petroleum Economist, Vol. 41 (March 1974), pp. 87-89; "Iran Economic Agreement with France," The Petroleum Economist, Vol. 41 (August 1974), p. 295; and "Barter Deals Cut the Price of Oil," Business Week, May 12, 1975, p. 30. 9. Vladimir Pertot, International Economics of Control (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1972), p. 238. Journal of Marketing, April 1976 20 barter deals as threatening the world with a vicious cycle of competition, anarchy, rivalry, and depression similar to those conditions that led to the collapse of world order in the 1930s. Fear of such a happening has led Dr. Kissinger to urge Western governments to stall bilateral barter agreements with the oil-producing countries while he strives for a stable and multinational solution to the oil problem.'° Nevertheless, in 1975 the U.S. was negotiating an accord under which Russia would deliver 200,000 bbl. per day of crude oil to the United States. Such an agreement with the Soviet Union, of course, would represent a reversal of the U.S.'s initial position toward oil bilateral deals. Types of International Barter Deals Four major types of barter deals are now regularly negotiated:" (1) clearing agreements, (2) switch trading, (3) parallel barter, and (4) buyback barter. To understand the significance of each of these types, a detailed analysis is necessary. Clearing Agreements This system of "straight" barter is particularly suitable for countries that lack a generally acceptable hzird currency and that have centrally planned economies. These characteristics, of course, best describe the economies of the Communist bloc; nearly all trade within Eastern Europe, as well as the majority of the trade of Eastern Europe and Russia with the developing countries, is done on this basis. What happens in a clearing agreement is that the contracting parties make a list of the commodities available for trade and agree each year 10. "Trade: A Payments Deficit Haunts Oil Consumers," same reference as footnote 8. 11. William A. Dymsza, "East-West Trade: Types of Business Arrangements," MSU Business Topics, Vol. 19 (Winter 1971), pp. 22-28; R. J. Familton, "East-West Trade and Payments Relations," IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 17 (March 1970), pp. 170-210; Marshall I. Goldman, Detente and Dollars: Doing Business with the Soviets (New York: Basic Books, 1975), pp. 177-180; Albert Masnata, East-West Economic Cooperation: Problems and Solutions (Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books, 1974); David St. Charles, "EastWest Business Arrangements: A Typology," in Changing Perspective in East-West Commerce, Carl H. McMillan, ed. (Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books, 1974), pp. 105-124; Hon. A. Maxwell Stamp, "Services by Specialist Organizations which Encourage East-West Transactions," in Financing East-West Business Transactions (New York: American Management Assn., Series No. 119, 1968), pp. 44-48; "Back to Barter," The Economist, December 14, 1974, pp. 52-53; Developing the East European Market (Geneva, Switzerland: Business International, 1966), pp. 47-51; and East-West Trade: The Lessons from Experience (New York: The Conference Board, Report No. 527, 1971). on the quantities and values to be exchanged. The aim is equal exchange so that no transfer of money need occur. However, clearing agreements normally provide a certain flexibility so that either side may accumulate limited export or import surpluses for short periods. The system of "clearing arrangements" has also been widely used by Russia and its satellites to establish new trading areas, particularly in the developing world. Typical is the major barter deal between Russia and Morocco that was negotiated in early 1974. The specifications of the agreement call for Russia to build a phosphate mine in Morocco in return for up to five million tons of phosphate a year through the 1980s and ten million tons a year thereafter. The agreement seems straightforward enough, but tied to it is a commitment by Morocco to import Russian petroleum products, timber, and industrial plant in return for citrus fruits. One disadvantage of this sort of deal is that countries can easily find themselves saddled with barter goods for which they have no use in the long run and which they must eventually "dump" on the world market. In fact, this very disadvantage has led to a secondary barter market: the "switch trading" system. In this system, the services and expertise of professional switch dealers are used. Switch-Trading System The switch-trading technique is required when a Western firm accepts payment from the East in the form of "clearing dollars" for which it has no direct use.'^ These clearing dollars represent a bookkeeping unit that is universally accepted for the accounting of trade between countries and parties whose commercial relationship is based on bilateral agreements. Recently, the use of clearing dollars has become more and more popular in East-West trade. Since the Western firm is not equipped to handle the accumulated clearing dollars, it is advisable to hire professional switch dealers who can assist in arranging such transactions.'^ To understand how the switching system 12. Donald V. Petroni, "Doing Business in Eastern European Countries," in Private Investors Abroad: Structures and Safeguards, Virginia Shook Cameron, ed. (New York: Matthew Bender and Co., 1966), pp. 261-326; Isaac Shapiro, "Obstacles to Trade with and Investment in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe," Private Investors Abroad: Problems and Solutions in International Business in 1969, Virginia Shook Cameron, ed. (New York: Matthew Bender and Co., 1969), pp. 173-190; and Charles H. Baudoin, "The Use of Switch Financing to Facilitate East-West Business Transactions," in Financing East-West Business Transactions (New York: American Management Assn., Series No. 119, 1968). 13. Stamp, same reference as footnote 11. The Reincarnation of Barter Trade works, let us consider the following hypothetical example. East Germany, a "soft-currency" country, has a bilateral agreement with a Swedish firm to swap $10 million worth of goods. The Swedes may find only $5 million of East German goods that they consider worth exchanging, so they have a $5 million credit. The switch dealer buys the credit for hard currency at a discount of 7% or more.'"* He then persuades an Indian importer to buy tractors in East Germany. His inducement would be a percentage of the dfscount he received when he bought the credit. He now has a credit in rupees, also a soft currency. He shops around and finds an Austrian firm that wants Indian cotton and is willing to pay hard currency for it. His inducement to the Austrian firm would be another percentage of the initial discount. As the above example indicates, the task of the switch dealer can become fantastically complicated. It involves selling a commodity for a soft currency, using the soft currency to buy another commodity, and repeating the process until the switcher gets a commodity that can eventually be sold for a hard currency." The ultimate possession of the hard currency brings an end to the switching process and the switch dealer is then ready to begin another deal. Parallel Barter Another barter system familiar to Western businesspeople is most often called "parallel barter" or "compensation trading." A major portion of the West's trade with Eastern Europe and Russia is done under this system. The fact that most Western countries will only provide credit for exports that are paid for in cash presents a problem for Eastern European economies, which are notoriously short of hard cash. The parallel barter agreement circumvents this difficulty by arranging two separate contracts. The trading begins when the Western manufacturing company negotiates an export contract for cash settlement; then under a quite separate contract, the Western company undertakes to buy goods from the importing country. The Western company then sells these goods and completes the trading cycle. The final result is a reduction in the net outflow of currency from the importing country. Thus, a British exporter of a chemical plant to 14. For a recent listing of clearing discounts, refer to Robert S. Kretschmar, Jr. and Robin Foor, The Potential of Joint Ventures in Eastern Europe (New York: Praeger, 1972), p. 99. 15. Paula Smith, "The Answer Man in Soviet Trade," Duns Review, Vol. 106 (October 1975), pp. 58-61 ff. 21 Poland may find himself selling Polish-built Fiat cars in Argentina in order to get his money. Typical is the recent barter deal between General Motors and Russia. General Motors agreed to supply Russia with $100 million worth of earthmoving equipment in return for timber—a product for which General Motors has little direct use, but for which it can easily find a cash market elsewhere. Another example is the barter deal between PepsiCo and Russia. PepsiCo agreed to swap Pepsi syrup and bottling plants for Russian vodka. A specialized barter trader normally negotiates the terms of these parallel barter deals.'* The goods offered are usually those that, by definition, are hardest to market for cash. The barter trader therefore will scan the products carefully, assessing "where in the world" he will be able to sell a cargo of, say, Russian vodka for convertible currency. The fee that the barter trader charges the exporter for taking on the counterpurchase commitment depends on what sort of goods he is offered and how he can sell them. Buy-Back Barter Among the international barter systems, buyback is frequently used by "transideological corporations, " which are jointly owned and operated by a Western firm and a Communist country.'^ Under this barter system, the transideological corporation in the West barters technical knowledge to build, or actually builds, a factory in return for promising to purchase some of its output once it is in operation. These buy-back barter deals are attractive to both parties of the agreement. For example, the Western partner will find that production within an Eastern country can be a way of reducing costs, as labor costs in the Communist countries are relatively low by Western standards. In fact, for many products marketed by transideological corporations in the West, the labor-cost differential more than offsets the transport costs involved in importing the product to the West.'* Further16. A sample of major switch and barter houses can be found in Christopher E. Stowell, Scn-iet Industrial Import Priorities: With Marketing Considerations for Exporting to the USSR (New York: Praeger, 1975), Appendix 12D, pp. 491494; Developing the East European Market, same reference as footnote 11, p. 48; and Stamp, same reference as footnote 11. 17. H. V. Perlmutter, "Emerging East-West Ventures: The Transideological Enterprise," Columbia Journal of World Business, Vol. 4 (September-October 1969), pp. 39-50. 18. G. Peter Lauter and Paul M. Dickie, "Multinational Corporations in Eastern European Socialist Economies," JOURNAL OF MARKETING, Vol. 39 (October 1975), pp. 40-46; and Leon Zurawicki, "The Cooperation of the Socialist State 22 more, production in the East may be seen by some transideological corporations as a means of offsetting the emerging countervaihng power of muhinational unionism." Communist countries are notorious for keeping labor unions in line; unlike their Western counterparts, labor unions in most of these countries do not have the power to strike. Such deals are equally advantageous for the Eastern partner. For one thing, they are a way of committing Western enterprises more deeply to the success of each project. Most Easterners are becoming increasingly unhappy with the straight licensing deals that were forerunners of the emerging "transideological joint ventures": the royalties were expensive in hard currency, the processes often broke down for want of servicing or advice, and there was no guarantee of markets in the West for the goods produced. The buy-back system requires the careful planning and involvement of the Western partner at all phases of the operation. In addition, such deals enable the Communists to master and apply the latest Westem organizational and management methods as well as the marketing techniques that produce results in the highly competitive Western markets.'^ The remarkable Mr. Hammer of Occidental Petroleum has undoubtedly set a pattern in the use of the buy-back barter system by offering to take payment in goods in every one of his many deals with Russia.^' In a less publicized move, Wilkinson Sword recently built a factory in Russia and has undertaken to buy back a proportion of the blades it produces. One drawback to the buy-back barter system is that the Western corporation often finds itself having to take back products that compete with its own production in the West, and so it is helping to build up a potential competitor. MasseyFerguson, for example, recently made a buy-back deal with Poland under which it will import tractor parts from Poland to assembly plants in Western Europe and Canada that directly compete with its own plant. Similarly, Fiat is currently facing severe competition from the Togliattigrad auto plant, which was designed and built by Fiat engineers in the Soviet Union. The Russians are with the MNC's," Columbia Joumal of World Business, Vol. 10 (Spring 1975), pp. 109-115. 19. John Alan James et al., "Multinational Trade Unions Muscle Their Strength," European Btisiness, No. 39 (Autumn 1973), pp. 36-46; and "The Unions Move Against Multinationals," Business Week, July 24, 1971, pp. 48-52. 20. Same reference as footnote 14, pp. 15-16. 21. "Armand Hammer: On Trade With Russia," BM5i>iess Week. July 13, 1974, pp. 64-66. Journal of Marketing, April 1976 exporting the Russian-built Fiats to Western Europe, where they are underselling Fiat." To avoid a similarly disastrous situation, General Motors is seeking more stringent clauses as part of its buy-back deal with Poland. GM will supply licenses and technology to produce lightweight vans; in return, GM will get a portion of the output as barter payment. The giant American automaker is trying to obtain the exclusive rights to market the bartered Polish-built vans anywhere outside Poland.^^ Chaiienges of internationai Barter Deals While international barter deals have proved beneficial for many Western corporations, these firms have had to come to grips with new and different bureaucratic, organizational, social, and economic problems. Negotiating such deals can be a painful experience.^'' Barter negotiations with the Eastern bloc take an extraordinarily long time due to a variety of bureaucratic problems. Patience on the part of the Western businessperson is more than a virtue; it is a necessity if a deal is to materialize. Western managers are also finding that radical changes in organizational structures may be necessary to cope with special problems of East-West trade. Noteworthy is the apparent trend toward setting up a regional sales or coordinating office for marketing in the Communist countries. Siemens of West Germany, for example, centralized much of its East-West activity in its new Zentralvertrieb Ost (ZVO) several years ago. ZVO is basically a staff department that does market research, airranges for a coordinated company exhibition at Eastern trade fairs, and signs company cooperation agreements with the Communist agencies. It also coordinates purchases under barter agreements, because a division selling to the East may not realize that another Siemens division can use the Eastern product being offered in exchange.-' But perhaps the most important challenge facing Western managers is to leam to handle the different economic and social systems encoun22. "A Russian-Made Fiat Gives Fiat Competition," Business Week. June 9, 1975, p. 38. 23. "East Bloc: Where the Demand for Trucks is Booming, " Business Week, October 20, 1975, p. 60; and "World Roundup: Poland," Business Week, October 27, 1975, p. 39. 24. East-West Trade: The Lessons from Experience, same reference as footnote 11. 25. Thomas A. Wolf, "New Frontiers in East-West Trade," European Business. No. 39 (Autumn 1973), p. 35. 23 The Reincarnation of Barter Trade tered in the Communist world." East-West trade may be an important test for the Western company's ability to survive in a completely different social context. Those executives who are able to play East-West business and excel may well be the entrepreneurs who will be charting new directions for the Western corporations in the remaining two decades of this century. Types of Domestic Barter Deals The preceding discussion focused on international barter trade and the challenges associated with it. However, barter deals are also gaining importance within the U.S. domestic market as a result of current economic conditions. The epidemic of shortages that struck the U.S. economy in late 1973 caught businesses off guard. Almost overnight, companies found themselves scrambling for a wide variety of basic commodities. Consequently, marketing attention is being forced to shift from the "seller" side to the "buyer" In this new environment, the role of the purchcising department is becoming more crucial to the whole organization.^* For example, during the early 1970s the purchasing department paid much attention to methods of restraining vendor price increases. In late 1973, however, a new problem became paramount: assuring a guaranteed supply of vital materials that if not acquired could result in the shutdown of a plant. Consequently, the purchasing manager is faced with a dual problem: restraining price increases, while still obtaining scarce materials that are vital for plant operation. To resolve these problems, many purchasing and marketing managers are resorting to barter trade. A great deal of barter trade, especially for chemicals and steel products, is now being conducted within the U.S. domestic market.-' At least 26. John P. Hardt. George D. Holliday, and Young C. Kim, Western Investment in Communist Economies, A Selective Sun'ey on Economic Interdependence, released by Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Multinational Corporations (Washington. DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, July 1974). 27. Philip Kotler and Sidney Levy, "Buying is Marketing Too!" JOURNAL OF MARKETING, Vol. 37 (January 1973), pp. 54-59. 28. "Marketing When the Growth Slows, Business Week, April 14, 1975, p. 48. 29. "Bartering to Beat the Chemicals Shortage." Business Week, October 27, 1973, pp. 90-91+; "Swapping: Widespread, Detested and Necessary." Chemical Week, May 1, 1974, pp. 10-11; "Many Companies Tum to Bartering as a Way to Get Vital Materials," Wall Street Joumal. February 13. 1974, pp. 1, 25, and "The Sultans of Swap," Tiwe, March ll! 1974, p. 87. three types of barter deals are regularly negotiated: (1) straight barter, (2) reverse reciprocity, and (3) advertising-media barter. Straight Barter Many purchasing departments have grown to include a position for barter agent, sometimes referred to as "scrounger," because more and more suppliers are refusing to sell for money.'" Instead, they present the buyer with a "shopping list" (rather than a price list) of products they need and for which they are willing to barter their products. This kind of buying and selling is not done only in exceptional instances; the growing importance of barter trade is confirmed by the findings of a research study conducted by Purchasing World.^^ The findings reveal that close to half of the 3(X) corporate purchasing managers responding to the study admitted that they were bartering to secure scarce products and materials. Another 10% said that they expected to be forced into the barter situation at anv time. Reverse Reciprocity A slightly more complex version of the straight barter system is the two-party reverse reciprocity system, which involves "I'll sell to you if you'll sell to me." Then, too, reverse reciprocity sometimes includes a third party: "I'll sell to you if you'll sell to my supplier." Like straight barter, reverse reciprocity is also used by a company during a period of shortages in order to obtain scarce materials vital for plant operation. To discover the degree to which "reverse reciprocity " is being practiced, Monroe Bird conducted a regional survey of industrial purchasing managers.^- He reports that 21% of the respondents admitted that their firms were actually practicing reverse reciprocity, while 77% agreed that they would use it if, through its use, they would meet their firms' basic purchasing needs. However, only 44% of the respondents thought reverse reciprocity was legal, while 56% felt that the practice was ethical. 30. "New Hires, Transfers Beef Up Buying Staffs," Purchasing. May 21, 1974, pp. 37, 45; and G. Tavemier, "The Rising Importance of the Purchasing Manager," Intemattonal Management, Vol. 29 (September 1974), pp. 42-52. 31. "Many Companies Turn to Bartering," same reference as footnote 29. 32. Monroe M. Bird, "Reverse Reciprocity: A New Twist in Industrial Buying Behavior" (Paper presented at the Southwestern Marketing Association meeting in Houston, Texas, March 5-8, 1975). Journal of Marketing, April 1976 24 Advertising-Media Barter While straight barter and reverse reciprocity are flourishing because of chronic shortages, the advertising-media barter is developing because manufacturers are short on cash and overloaded with inventory. Under this system, a manufacturer hires a barter broker who arranges deals whereby the manufacturer and the advertising medium (usually television or radio) agree to swap excess inventory for free commercial time.'' The most publicized media barter deal involved Schick, Inc., which tound itself overstocked with a product called "Warm'n Creamy," a hot facial cream appliance. To get rid of it, Schick hired a barter company which set up a deal whereby Schick swapped its unsalable inventory for free commercial time with a television station. Other large manufacturers who occasionally rely on barter trade include Chrysler, Clairol, Gillette, General Electric, Norelco, and Oster.'" Problems of Domestic Barter Deals Even though a great deal of barter business goes on within the U.S. domestic market, the legality of such deals may be open to question, which raises the following issue: From a legal viewpoint, what is the difference between straight barter, reverse reciprocity, and advertising-media barter? Currently, there are two schools of thought on this issue. The first claims that straight barter and advertising-media barter are legal swapping, but that reverse reciprocity violates antitrust laws. The second says that the three are synonymous and that sticking to hard cash is the best way to avoid running afoul of the law. But legal or not, there is no question that barter is on the upswing. In 1974 the Federal Trade Commission claimed that barter was becoming a standcird way for many of the country's largest corporations to obtain vital scarce materials. The FTC is particularly worried because such deals skirt the federal laws of competition, and smaller firms have been complaining that the barter market is divided among the big companies, which swap their stockpiles of raw materials among themselves as required to fill any shortages.'' James T. Halverson, director of the FTC's Bureau of Competition, recently discussed the FTC's general policy on allegedly discriminatory tie-in deals, especially with regard to the situation during periods of shortages: 33. "A Barter Boom in Advertising," Business Week, April 7, 1975, pp. 52-54. 34. Same reference as footnote 33, p. 52. 35. A. N. Wecksler, "Bartering Is Going on . . . But Is It Legal?" Purchasing, Vol. 76 (May 21, 1974), p. 11. We are particularly concerned about the survival of small non-integrated firms whose sources of supply have been cut off or are likely to be cut off. In some industries we anticipate that formerly independent producers may attempt to integrate backward to form new integrated firms to guarantee sources of supply. Equally important, large vertically integrated firms may attempt to buy out the independents. Such a trend toward increased concentration and vertical integration would further decrease supplies available in the open market and could have a permanent effect on the competitive situation in specific industries.'* Mr. Halverson's comment indicates that the legality of such barter agreements may be open to question; but until some legal precedent is established, marketers are considering them as methods of coping with the prevailing economic crisis. However, a further complication exists in that the Intemal Revenue Service is scrutinizing the tax implications of barter deals." Since part of the value of merchandise received through barter deals constitutes taxable income, the IRS expects corporations to report their barter agreements. Yet, even if barter deals are reported to the IRS, it is difficult to assign monetary value to them. Conclusions The revival of the barter system in response to current economic conditions has produced an important tool in international marketing. In response to the unique complications inherent in trading with the Communist nations, the author suggests the establishment of a financial institution designed to stimulate and facilitate EastWest trade either by accepting Eastern trade debts or by acting as an agent or clearing house for international barter agreements. Current economic conditions have also created an upsurge in barter trade in the U.S. domestic market. No longer an activity solely of the Communist bloc or developing nations, the system has been adopted by the sophisticated marketers of the West as well. While international barter deals are recognized as legal marketing techniques, the legal and tax implications of domestic barter deals may be open to question. Until some legal precedent is established, however, marketers are considering barter business as one means of coping with the prevailing economic crisis. 36. Same reference as footnote 35. 37. "The Sultans of Swap," same reference as footnote 29. The author wishes to thank Professor Warren B. Nation of Florida State University for his helpful suggestions and valuable comments on an earlier draft of this article.