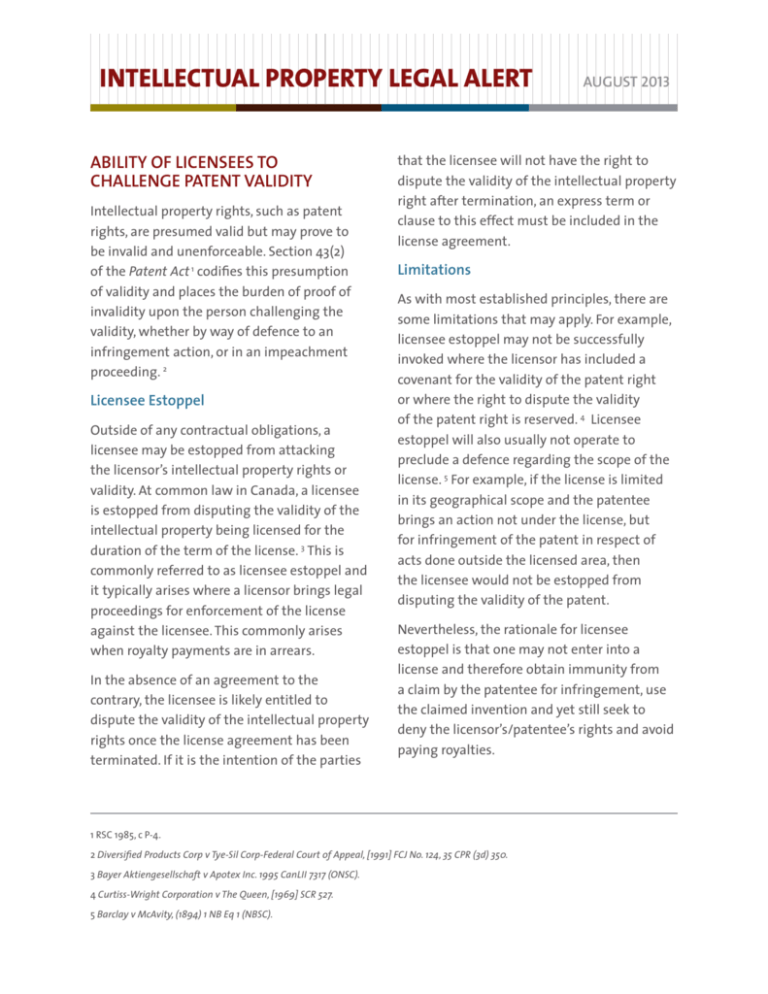

Ability of Licensees to Challenge Patent Validity

advertisement

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LEGAL ALERT ABILITY OF LICENSEES TO CHALLENGE PATENT VALIDITY Intellectual property rights, such as patent rights, are presumed valid but may prove to be invalid and unenforceable. Section 43(2) of the Patent Act 1 codifies this presumption of validity and places the burden of proof of invalidity upon the person challenging the validity, whether by way of defence to an infringement action, or in an impeachment proceeding. 2 Licensee Estoppel Outside of any contractual obligations, a licensee may be estopped from attacking the licensor’s intellectual property rights or validity. At common law in Canada, a licensee is estopped from disputing the validity of the intellectual property being licensed for the duration of the term of the license. 3 This is commonly referred to as licensee estoppel and it typically arises where a licensor brings legal proceedings for enforcement of the license against the licensee. This commonly arises when royalty payments are in arrears. In the absence of an agreement to the contrary, the licensee is likely entitled to dispute the validity of the intellectual property rights once the license agreement has been terminated. If it is the intention of the parties that the licensee will not have the right to dispute the validity of the intellectual property right after termination, an express term or clause to this effect must be included in the license agreement. Limitations As with most established principles, there are some limitations that may apply. For example, licensee estoppel may not be successfully invoked where the licensor has included a covenant for the validity of the patent right or where the right to dispute the validity of the patent right is reserved. 4 Licensee estoppel will also usually not operate to preclude a defence regarding the scope of the license. 5 For example, if the license is limited in its geographical scope and the patentee brings an action not under the license, but for infringement of the patent in respect of acts done outside the licensed area, then the licensee would not be estopped from disputing the validity of the patent. Nevertheless, the rationale for licensee estoppel is that one may not enter into a license and therefore obtain immunity from a claim by the patentee for infringement, use the claimed invention and yet still seek to deny the licensor’s/patentee’s rights and avoid paying royalties. 1 RSC 1985, c P-4. 2 Diversified Products Corp v Tye-Sil Corp-Federal Court of Appeal, [1991] FCJ No. 124, 35 CPR (3d) 350. 3 Bayer Aktiengesellschaft v Apotex Inc. 1995 CanLII 7317 (ONSC). 4 Curtiss-Wright Corporation v The Queen, [1969] SCR 527. 5 Barclay v McAvity, (1894) 1 NB Eq 1 (NBSC). AUGUST 2013 INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY & INNOVATION (TECHCOUNSEL®) LEGAL ALERT Recommendations for licensors and licensees Canadian licensors will often include license provisions that prohibit licensees from challenging licensed patents. These provisions may be valid under Canadian law but there can be difficulties with such terms in respect of certain types of intellectual property in the United States, Europe, and Japan. Limitations to the common law doctrine of licensee estoppel may lead licensors to consider introducing explicit contractual provisions in the license agreement to account for the increased likelihood of such validity challenges. It may be useful to a licensor to obtain an acknowledgment from the licensee that it will not, either during the term of the license or following termination, attack the intellectual property validity and it will not assist any third parties in doing so. Conversely, licensees would be well-advised to expressly retain the right to challenge the validity of the licensed patent. It may prove difficult to dispute the enforceability of a signed “no-challenge” clause by the licensee especially where they exercised due diligence prior to finalizing the agreement. Such clauses however, may attract larger upfront license fees, increased royalty rates or licensor’s right to terminate upon a licensee’s challenge of the intellectual property rights as well as a right to receive advance notice of the licensee’s claims. 2 There are also some contractual clauses short of prohibiting challenges to the licensed patent that licensors can stipulate as part of the license agreement. Licensors may include a right to reduce the scope of the license if the licensee challenges the patent’s validity. For example, an exclusive license could be converted to a non-exclusive license, or reductions in the field of use may be applied. Further, licensors may be well-advised to require licensees to conduct pre-licensing due diligence on the licensor’s patent and recite in the agreement the licensee’s conclusion that the patent is valid and that the licensee found no basis to invalidate it. The enforceability of these contractual clauses is yet to be established, but courts will likely adopt a factual analysis in determining their practical and legal consequences. Their enforceability may also depend upon their position on the “disincentive-to-challenge” spectrum. The more drastic the consequences of the deterring contractual clauses, the more probable these terms will be held unenforceable. For more information please contact Michael Sharp 780.423.8697 msharp@parlee.com Practice Group Chair: Bruce D. Hirsche, Q.C. 780.423.8540 bhirsche@parlee.com Or any member of our Intellectual Property & Innovation (TechCounsel®) Practice Group Disclaimer This legal alert is intended to provide general information concerning developments in the law and is not intended to provide legal advice in respect of any particular situation. Edmonton Calgary www.parlee.com