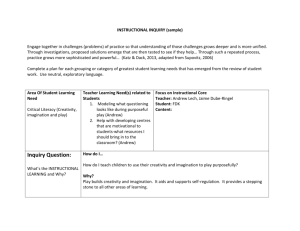

organizational culture & change

advertisement