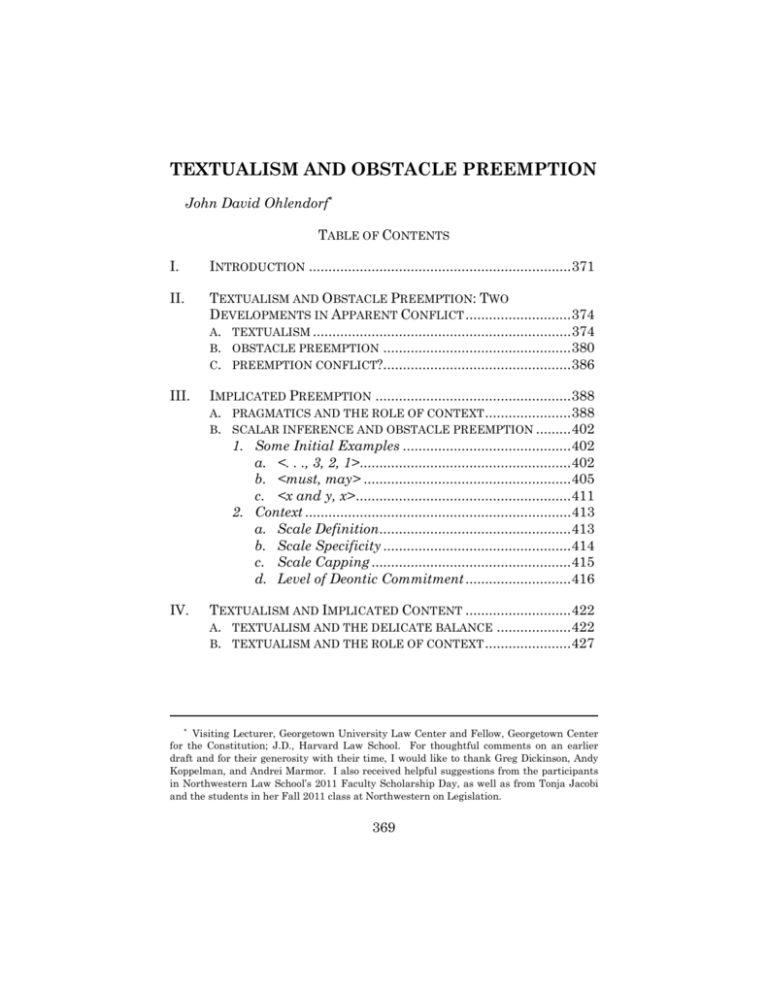

textualism and obstacle preemption

advertisement