Secondary Traumatic Stress

A Fact Sheet for Child-Serving Professionals

“…We are stewards not just of those who

allow us into their lives but of our own

capacity to be helpful...”1

Each year more than 10 million children in the

United States endure the trauma of abuse,

violence, natural disasters, and other adverse

events.2 These experiences can give rise to

significant emotional and behavioral problems

that can profoundly disrupt the children’s

lives and bring them in contact with childserving systems. For therapists, child welfare workers, case managers, and other helping

professionals involved in the care of traumatized children and their families, the essential

act of listening to trauma stories may take an emotional toll that compromises professional

functioning and diminishes quality of life. Individual and supervisory awareness of the impact

of this indirect trauma exposure—referred to as secondary traumatic stress—is a basic part

of protecting the health of the worker and ensuring that children consistently receive the best

possible care from those who are committed to helping them.

Our main goal in preparing this fact sheet is to provide a concise overview of secondary

traumatic stress and its potential impact on child-serving professionals. We also outline

options for assessment, prevention, and interventions relevant to secondary stress, and

describe the elements necessary for transforming child-serving organizations and agencies

into systems that also support worker resiliency.

How Individuals Experience Secondary Traumatic Stress

Secondary traumatic stress is the emotional duress that results when an individual hears

about the firsthand trauma experiences of another. Its symptoms mimic those of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Accordingly, individuals affected by secondary stress may

find themselves re-experiencing personal trauma or notice an increase in arousal and avoidance reactions related to the indirect trauma exposure. They may also experience changes

in memory and perception; alterations in their sense of self-efficacy; a depletion of personal

This project was funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), US Department

of Health and Human Services (HHS). The views, policies, and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect those of SAMHSA or HHS.

resources; and disruption in their perceptions of safety, trust, and independence. A partial list

of symptoms and conditions associated with secondary traumatic stress includes3

n

Hypervigilance

n

Hopelessness

n

Inability to embrace complexity

n

Inability to listen, avoidance of clients

n

Anger and cynicism

n

Sleeplessness

n

Fear

Secondary traumatic stress refers to the

presence of PTSD symptoms caused by at

least one indirect exposure to traumatic

material. Several other terms capture

elements of this definition but are not all

interchangeable with it.

n

Chronic exhaustion

n

n

Physical ailments

n

Minimizing

n

Guilt

Secondary Traumatic Stress

and Related Conditions:

Sorting One from Another

Compassion fatigue, a label proposed by

Figley4 as a less stigmatizing way to describe

secondary traumatic stress, has been used

interchangeably with that term.

Vicarious trauma refers to changes

in the inner experience of the therapist

resulting from empathic engagement with a

traumatized client.13 It is a theoretical term

that focuses less on trauma symptoms

and more on the covert cognitive changes

that occur following cumulative exposure to

another person’s traumatic material. The

primary symptoms of vicarious trauma are

disturbances in the professional’s cognitive

frame of reference in the areas of trust,

safety, control, esteem, and intimacy.

n

Clearly, client care can be compromised if the

therapist is emotionally depleted or cognitively

affected by secondary trauma. Some traumatized professionals, believing they can no longer

be of service to their clients, end up leaving

their jobs or the serving field altogether. Several

studies have shown that the development of

secondary traumatic stress often predicts that

the helping professional will eventually leave the

field for another type of work.4,5

Understanding Who is at Risk

The development of secondary traumatic stress

is recognized as a common occupational hazard

for professionals working with traumatized

children. Studies show that from 6% to 26% of

therapists working with traumatized populations,

and up to 50% of child welfare workers, are at

high risk of secondary traumatic stress or the

related conditions of PTSD and vicarious trauma.

Any professional who works directly with

traumatized children, and is in a position to

Burnout is characterized by emotional

exhaustion, depersonalization, and a reduced

feeling of personal accomplishment. While

it is also work-related, burnout develops as

a result of general occupational stress; the

term is not used to describe the effects of

indirect trauma exposure specifically.

n

Compassion satisfaction refers to the

positive feelings derived from competent

performance as a trauma professional. It is

characterized by positive relationships with

colleagues, and the conviction that one’s

work makes a meaningful contribution to

clients and society.

n

Secondary Traumatic Stress: A Fact Sheet for Child-Serving Professionals

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

www.NCTSN.org

2

hear the recounting of traumatic experiences, is at risk of secondary traumatic stress. That

being said, risk appears to be greater among women and among individuals who are highly

empathetic by nature or have unresolved personal trauma. Risk is also higher for professionals

who carry a heavy caseload of traumatized children; are socially or organizationally isolated;

or feel professionally compromised due to inadequate training.6-8 Protecting against the

development of secondary traumatic stress are factors such as longer duration of professional

experience, and the use of evidence-based practices in the course of providing care.7

Identifying Secondary Traumatic Stress

Supervisors and organizational leaders

in child-serving systems may utilize a

variety of assessment strategies to help

them identify and address secondary

traumatic stress affecting staff

members.

The most widely used approaches are

informal self-assessment strategies,

usually employed in conjunction with

formal or informal education for the

worker on the impact of secondary traumatic stress. These self-assessment

tools, administered in the form of questionnaires, checklists, or scales, help

characterize the individual’s trauma

history, emotional relationship with work and the work environment, and symptoms or experiences that may be associated with traumatic stress.4,9

Supervisors might also assess secondary stress as part of a reflective supervision model.

This type of supervision fosters professional and personal development within the context of

a supervisory relationship. It is attentive to the emotional content of the work at hand and

to the professional’s responses as they affect interactions with clients. The reflective model

promotes greater awareness of the impact of indirect trauma exposure, and it can provide a

structure for screening for emerging signs of secondary traumatic stress. Moreover, because

the model supports consistent attention to secondary stress, it gives supervisors and

managers an ongoing opportunity to develop policy and procedures for stress-related issues

as they arise.

Formal assessment of secondary traumatic stress and the related conditions of burnout,

compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction is often conducted through use of the

Professional Quality of Life Measure (ProQOL).7,8,10,11 This questionnaire has been adapted to

measure symptoms and behaviors reflective of secondary stress. The ProQOL can be used

at regular intervals to track changes over time, especially when strategies for prevention or

intervention are being tried.

Secondary Traumatic Stress: A Fact Sheet for Child-Serving Professionals

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

www.NCTSN.org

3

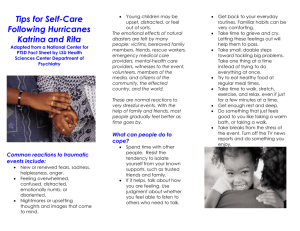

Strategies for Prevention

Prevention

A multidimensional approach to prevention and

n Psychoeducation

intervention—involving the individual, supervisors,

n Clinical supervision

and organizational policy—will yield the most

n Ongoing skills training

positive outcomes for those affected by secondary

n Informal/formal self-report screening

traumatic stress. The most important strategy

n Workplace self-care groups

for preventing the development of secondary

(for example, yoga or meditation)

traumatic stress is the triad of psychoeducation,

n Creation of a balanced caseload

skills training, and supervision. As workers

n Flextime scheduling

gain knowledge and awareness of the hazards

n Self-care accountability buddy system

of indirect trauma exposure, they become

n Use of evidence-based practices

empowered to explore and utilize prevention

n Exercise and good nutrition

strategies to both reduce their risk and increase

their resiliency to secondary stress. Preventive

strategies may include self-report assessments,

participation in self-care groups in the workplace, caseload balancing, use of flextime

scheduling, and use of the self-care accountability buddy system. Proper rest, nutrition,

exercise, and stress reduction activities are also important in preventing secondary

traumatic stress.

Strategies for Intervention

Although evidence regarding the effectiveness

of interventions in secondary traumatic stress

is limited, cognitive-behavioral strategies and

mindfulness-based methods are emerging as best

practices. In addition, caseload management,

training, reflective supervision, and peer

supervision or external group processing have been

shown to reduce the impact of secondary traumatic

stress. Many organizations make referrals for

formal intervention from outside providers such

as individual therapists or Employee Assistance

Programs. External group supervision services may

be especially important in cases of disasters or

community violence where a large number of staff

have been affected.

Intervention

n

Strategies to evaluate secondary

stress

n

Cognitive behavioral interventions

n

Mindfulness training

n

Reflective supervision

n

Caseload adjustment

n

Informal gatherings following crisis

events (to allow for voluntary,

spontaneous discussions)

n

Change in job assignment or work

group

n

Referrals to Employee Assistance

Programs or outside agencies

The following books, workbooks, articles, and self-assessment tests are valuable resources

for further information on self-care and the management of secondary traumatic stress:

n

Volk, K.T., Guarino, K., Edson Grandin, M., & Clervil, R. (2008). What about You? A Workbook for Those Who Work with Others. The National Center on Family Homelessness.

http://508.center4si.com/SelfCareforCareGivers.pdf

Secondary Traumatic Stress: A Fact Sheet for Child-Serving Professionals

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

www.NCTSN.org

4

n

Self-Care Assessment Worksheet

http://www.ecu.edu/cs-dhs/rehb/upload/Wellness_Assessment.pdf

n

Hopkins, K. M., Cohen-Callow, A., Kim, H. J., Hwang, J. (2010). Beyond intent to leave:

Using multiple outcome measures for assessing turnover in child welfare. Children and

Youth Services Review, 32,1380-1387.

n

Saakvitne, K. W., Pearlman, L. A., & Staff of TSI/CAAP. (1996). Transforming the Pain: A

Workbook on Vicarious Traumatization. New York: W.W. Norton.

n

Van Dernoot Lipsky, L. (2009). Trauma Stewardship: An everyday guide to caring for self while

caring for others. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

n

Compassion Fatigue Self Test

http://www.ptsdsupport.net/compassion_fatugue-selftest.html

n

ProQOL 5 http://proqol.org/ProQol_Test.html

n

Rothschild, B. (2006). Help for the helper. The psychophysiology of compassion fatigue and

vicarious trauma. New York: W.W. Norton.

Worker Resiliency in Trauma-informed Systems: Essential Elements

Both preventive and interventional strategies for secondary traumatic stress should

be implemented as part of an organizational risk-management policy or task force that

recognizes the scope and consequences of the condition. The Secondary Traumatic Stress

Committee of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network has identified the following

concepts as essential for creating a trauma-informed system that will adequately address

secondary traumatic stress. Specifically, the trauma-informed system must

n

Recognize the impact of secondary trauma on the workforce.

n

Recognize that exposure to trauma is a risk of the job of serving traumatized children

and families.

n

Understand that trauma can shape the culture of organizations in the same way that

trauma shapes the world view of individuals.

n

Understand that a traumatized organization is less likely to effectively identify its clients’

past trauma or mitigate or prevent future trauma.

n

Develop the capacity to translate trauma-related knowledge into meaningful action, policy,

and improvements in practices.

These elements should be integrated into direct services, programs, policies, and

procedures, staff development and training, and other activities directed at secondary

traumatic stress.

“We have an obligation to our clients, as well as to ourselves, our colleagues

and our loved ones, not to be damaged by the work we do.”12

Secondary Traumatic Stress: A Fact Sheet for Child-Serving Professionals

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

www.NCTSN.org

5

References

1. Conte, JR. (2009). Foreword. In L. Van Dernoot Lipsky, Trauma stewardship. An everyday guide to

caring for self while caring for others (p. xi). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Available at: http://traumastewardship.com/foreword.html Accessed June 12, 2011.

2. National Center for Children Exposed to Violence (NCCEV). (2003).

Available at: http://www.nccev.org/violence/index.html Accessed June 5, 2011.

3. Van Dernoot Lipsky, L. (2009). Trauma Stewardship: An everyday guide to caring for self while caring for

others. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

4. Figley, C.R. (1995). Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In C.R.

Figley (Ed.), Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the

traumatized (pp. 1-20). New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel.

5. Pryce, J.G., Shackelford, K.K., Price, D.H. (2007). Secondary traumatic stress and the child welfare

professional. Chicago: Lyceum Books, Inc.

6. Bride, B.E., Hatcher, S.S., & Humble, M.N. (2009). Trauma training, trauma practices, and secondary

traumatic stress among substance abuse counselors. Traumatology, 15, 96-105.

7. Craig, C.D., & Sprang, G. (2010). Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout in a

national sample of trauma treatment therapists. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 23(3), 319-339.

8. Sprang, G., Whitt-Woosley, A., & Clark, J. (2007). Compassion fatigue, burnout and compassion

satisfaction: Factors impacting a professional’s quality of life. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 12, 259-280.

9. Figley, C.R. (2004, October). Compassion Fatigue Therapist Course Workbook. A Weekend Training

Course. Green Cross Foundation. Black Mountain, NC.

Available at: http://www.gbgm-umc.org/shdis/CFEWorkbook_V2.pdf

10. Stamm, B.H. (2010). The concise ProQOL manual, 2nd Ed. Pocatello, ID: ProQOL.org.

Available at: http://www.proqol.org/uploads/ProQOL_Concise_2ndEd_12-2010.pdf

11. Stamm, B.H., Figley, C.R., & Figley, K.R. (2010, November). Provider Resiliency: A Train-the-Trainer Mini

Course on Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue. International Society for Traumatic Stress

Studies. Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

12. Saakvitne, K. W., & Pearlman, L. A., & Staff of TSI/CAAP. (1996). Transforming the Pain: A Workbook

on Vicarious Traumatization. New York: W.W. Norton.

13. Pearlman, L. A., & Saakvitne, K.W. (1995). Treating therapists with vicarious traumatization and

secondary traumatic stress disorders. In C.R. Figley (Ed.), Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary

traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized (pp. 150-177). New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel.

Recommended Citation

National Child Traumatic Stress Network, Secondary Traumatic Stress Committee. (2011). Secondary traumatic stress: A fact

sheet for child-serving professionals. Los Angeles, CA, and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

Copyright © 2011, National Center for Child Traumatic Stress on behalf of Ginny Sprang, PhD, Leslie Anne Ross, PsyD, and the

National Child Traumatic Stress Network. This work was funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which retains for itself and others acting on its behalf

a nonexclusive, irrevocable worldwide license to reproduce, prepare derivative works, and distribute this work by or on behalf of

the Government. All other rights are reserved by the copyright holder(s).

About the National Child Traumatic Stress Network

Established by Congress in 2000, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) is a unique collaboration of academic

and community-based service centers whose mission is to raise the standard of care and increase access to services for

traumatized children and their families across the United States. Combining knowledge of child development, expertise in the

full range of child traumatic experiences, and attention to cultural perspectives, the NCTSN serves as a national resource for

developing and disseminating evidence-based interventions, trauma-informed services, and public and professional education.