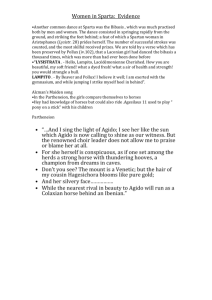

Rulers Ruled By Women - University of Virginia School of Law

advertisement