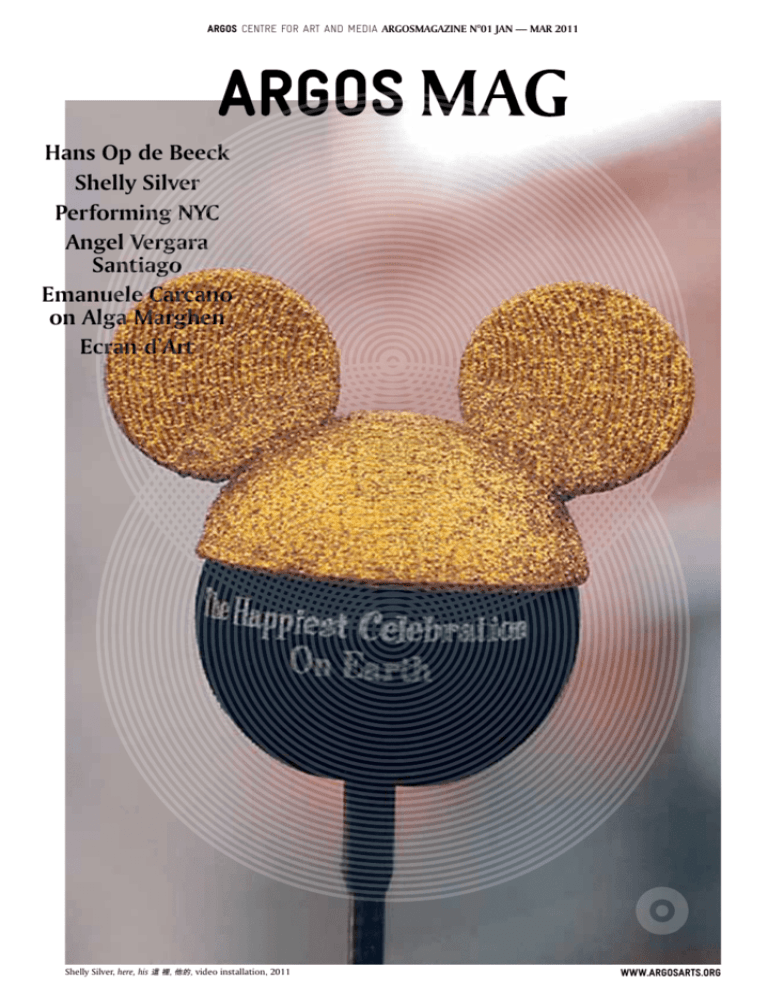

PDF magazine

advertisement