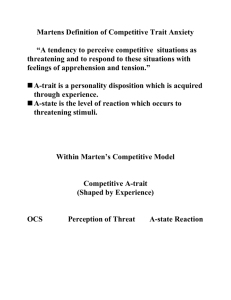

research

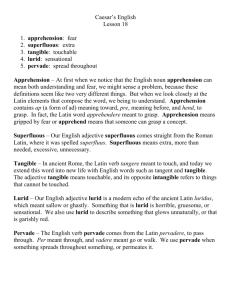

advertisement