Run-of-the-Mill Justice

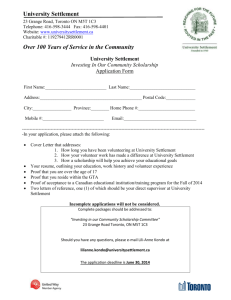

advertisement