report on food donations - EESC European Economic and Social

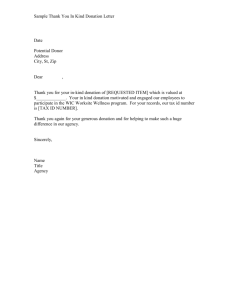

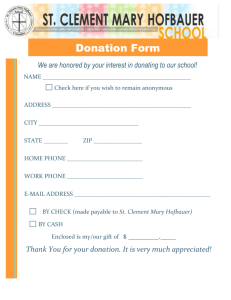

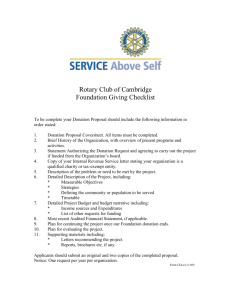

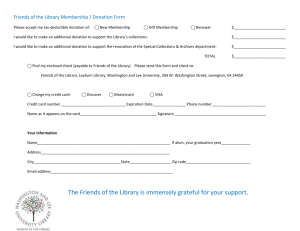

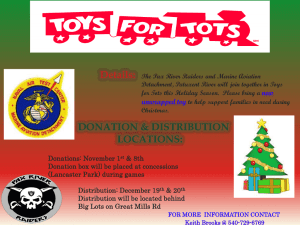

advertisement