how to analyse autobiographical narrative - Otto-von

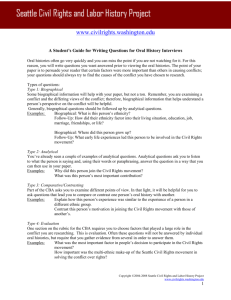

advertisement