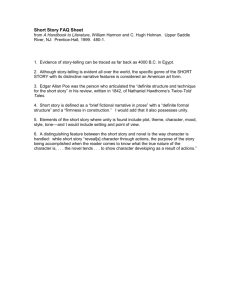

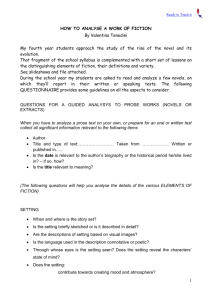

Master_Document_5 - UWSpace Home

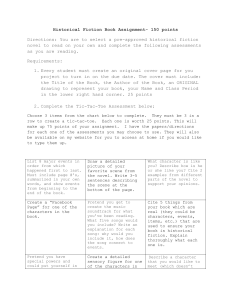

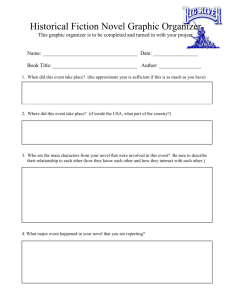

advertisement