Product Liability's Parallel Universe

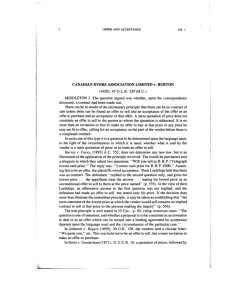

advertisement