the sea in beowulf, the wanderer and the seafarer

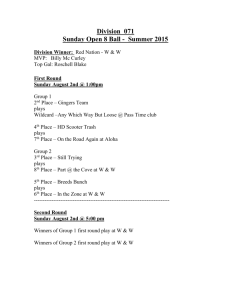

advertisement