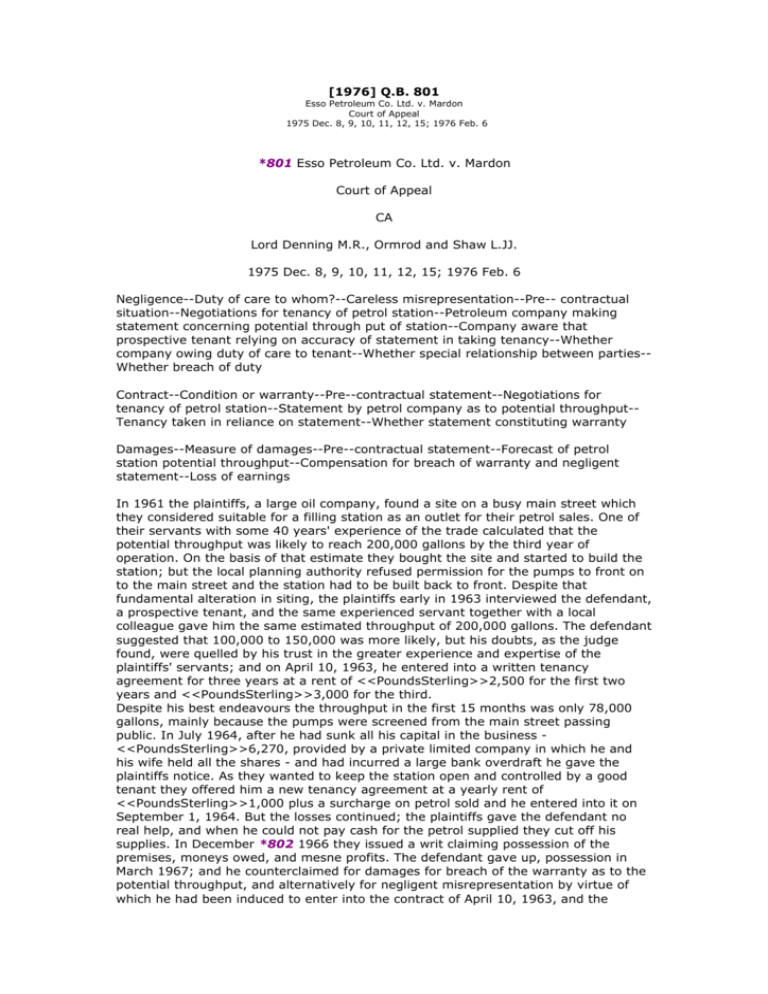

Esso Petroleum Co v Mardon

advertisement