Evaluation of Selected General Cognitive Ability Tests Employment

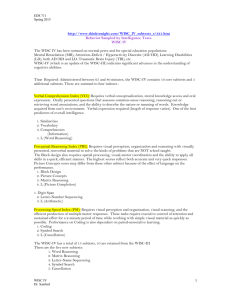

advertisement