Financial Management - Pathfinder International

advertisement

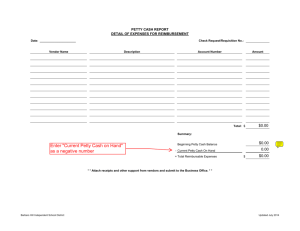

Financial Management • •STRUCTURE • Management Information Systems • SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Series 2 ORGANIZATIONAL MANAGEMENT • Impact • Assessment • Career Development • Strategic Planning • SYSTEMS • Supervision • Objectives • Program Module 3 Financial Management 2/ Financial Management Introduction Before you Begin Budgets and blueprints for your organization Characteristics of good budgets Step by step: Preparing a budget Tips and tools: Some standard budget categories Monitoring your budget Variances Vexing financial management issues ❐ Travel expenses ❐ Petty cash ❐ Income generation ❐ Procurement ❐ Inventories 1 2 3 3 4 6 8 11 11 Instituting effective financial controls ❐ Accounting controls ❐ Segregation of duties ❐ Managerial supervision 16 x Figures, Tables, and Exercises Figure 1: Exercise A: Exercise B: Financial management cycle Using a format to facilitate budget monitoring Identifying the types of costs your organization incurs Annexes Annex A: Annex B: Annex C: Annex D: Annex E: Annex F: Annex G: Model budget formats Travel authorization and expense report formats Petty Cash vouchers and ledgers Cash collection and contraceptive receipt/distribution formats Requisition forms and local purchase orders Internal questionnaires and checklists Model financial reports 1 9 10 For many managers, financial management is a mystery best left to those who toil with dusty ledgers, sharp pencils, even sharper eyesight, and the word “No” to many seemingly “simple” requests omnipresent in their conversations. While it is true that every organization needs strong financial management – and dedicated staff to provide it – effective managers must know basic information about, and have basic skills for, monitoring the fiscal health of their organization and each of its programs. This module will not make every manager a financial expert. This module will enable managers to: ☛ Review financial documents (budgets, reports, forecasts, procurement requests, income and expenditure statements) with comprehension. ☛ Understand budget preparation and monitoring. ☛ Recognize the importance of implementing sound financial controls. ☛ Monitor the impact of changing program plans on resource requirements and communicate effectively with financial staff. ☛ Use financial data and information for decision-making. ☛ Calculate realistic funding needs and identify appropriate sources. ☛ Minimize risks of financial difficulties for the organization. There are several ways to describe an organization’s financial management cycle. Some analysts tie financial management to receiving income and reporting income and expenditure to organizational policy makers (such as the Board) and to donors. The diagram in Figure 1 below takes a more functional approach, drawing key functions to managers’ attention before they focus on financial management. The module emphasizes the four critical aspects of financial management depicted in each box, helping managers to understand the importance of monitoring and institutionalizing financial controls. Figure 1: Financial Management Cycle Budgeting Financial Reporting Monitoring/Financial Monitoring/Financial Controls Controls Cash Flow Procurement Goods/Services Financial management is a multi-faceted, comprehensive set of interlocking skills and systems involving all the components depicted in Figure 1 and other aspects of sound management (e.g., planning, monitoring, procurement, MIS). An effective manager must integrate and 1 carefully monitor these aspects of an organization’s operations, balancing competing processes and concerns to ensure that the organization has adequate resources at all times. Clearly, financial management goes beyond traditional bookkeeping and accounting. Financial management is about analyzing financial performance, identifying ways to use resources efficiently, and finding creative means to use resources in order to generate additional resources. Financial management activities include:1 ✔ Matching available resources to planned activities. ✔ Ensuring effective teamwork, interdependent activities and systems, and good communication or information flow between financial and program staff. ✔ Monitoring the efficiency of resource use. ✔ Identifying ways to reduce and recover costs. ✔ Developing, monitoring, updating, and reporting on operational budgets. ✔ Finding ways to finance new initiatives. ✔ Tracking resource use trends in order to determine future budget requirements, project cash needs, and forecast financial growth. ✔ Developing long-term financial plans to meet future resource needs. ✔ Managing and investing future resources to make them profitable. ✔ Controlling and attempting to prevent major financial risks. 2 Before You Begin…Some Questions for Managers. Tick your responses to gather clues about priorities for improvement. ❐ Do you have a financial system that provides adequate information about your organization’s income and expenditures on an as-needed basis? Are you collecting data you truly need or it is excessive? ❐ Are your financial reports accurate, clear, complete, timely, and coordinated with your programmatic reports? ❐ Do you have an integrated organizational budget that reflects income and expenditures from all sources? ❐ Do you regularly review and update your budget? ❐ Can your accounting system monitor cost centers and segregate costs (including determining cost per unit)? ❐ Are you able to project and forecast resource needs or shortfalls before they occur? 1 Adapted from FPMD. The Manager Series. “Understanding and Using Financial Management Systems to Make Decisions,” Winter 1999 /2000, Volume VIII, Number 4. Boston, MA. ❐ Do you bring your financial and program staff together when preparing proposals or designing new initiatives and for regular consultations or operational plan reviews? ❐ Can the same person request, approve, and sign a check for goods or services? ❐ Does your organization have annual audits by a professional outside accounting firm? ❐ Do you monitor or review all systems involved in financial management on a regular basis? ❐ Have you linked your financial management system to monitoring indicators and to your organization’s strategic plan? ❐ Do you have a handbook or written policies that explain procedures and formats for routine financial transactions (e.g., accounting for travel or imprest funds, petty cash, requisitions or procurement, grants disbursements) to all staff? Do you regularly review and provide training regarding these policies? If the answer to any of these questions is No, you and your management team need to review financial management policies and procedures in great detail and develop plans to improve and strengthen them. Budgets as Blueprints for Your Organization Your organization’s budget is perhaps the most basic tool for sound financial management. A budget encompasses several related financial management issues: specific costs for activities or staff members; a plan of action for making expenditures; the number and kinds of human resources required to implement the program, and, implicitly, the amount of money needed to support an organization as it seeks to achieve its goals and objectives. Annex A contains two types of budgets: a budget allocating specific costs to budget categories and line items, and a cash flow budget. Every good manager should institutionalize a rigorous budget monitoring and review process, usually involving monthly income and expenditure reports (See an example in Annex G) or spreadsheets. These reports can serve as a basis for quarterly or other reports required by Boards and Directors or donors. The best managers also ensure that financial and program staff meet together regularly and provide inputs that help a manager make appropriate decisions about revising budgets, seeking increased revenues, or reallocating resources. Characteristics of Good Budgets2 A budget is a dynamic tool. It should reflect management decisions regarding allocation of resources, However, since a budget must be viewed in the context of an organization’s internal and external environments, it should be altered according to changes in those environments. Budgets and reports are used by managers to review projected costs against actual costs, to forecast cash needs, and even 2 Adapted from The Manager, Winter 1999/2000 op. cit. 3 as a marketing tool to leverage funds to ensure coverage of all expenses. The following are characteristics of a good budget: ✔ Budgets cover a defined set of activities. This means that every separate project or program should have its own budget. It is important, however, for program managers to combine all separate budgets into an organization-wide operations budget, and the advent of computers makes this a relatively simple action. Monitoring the entire organization’s fiscal health pays dividends because it allows a manager to determine opportunities for becoming more cost-effective, to estimate cash flow more efficiently, to use excess funds in one area to subsidize another under-funded area, and to predict where additional resources may be needed. ✔ Budgets state the time period covered. It is advisable for managers to prepare annual budgets, and to prepare them in tandem with annual work or operations plans. However, from time to time, dividing the budget into months or quarters may facilitate monitoring. 4 ✔ Budgets are realistic about expected revenues and expected costs. A budget should be based on prudent cost estimates. Too often, managers under- or overestimate the costs of particular line items or budget categories. Consequently, some organizations experience cash shortfalls or improper allocation of resources that demoralize staff and compromise program implementation. Ask financial staff to seek pro-forma invoices or cost estimates for major expenses (vehicles, computers, clinic equipment, etc.) and recurring costs (office stationery, telephone and bank charges, staff salaries, etc.) your office is likely to incur annually. This is one way to ensure good costing as a basis for preparing a budget. ✔ Budgets include indirect costs. One of managers’ most frequent problems with budgeting is that they only capture direct costs such as salaries, rent, supplies, and equipment. Yet, there are many indirect costs that influence how well an organization or a program operates. Fringe benefits – e.g., leave, pensions, insurance – and overhead (e.g., administration, services shared among various programs such as photocopying, telephones). Even the costs of financial management and administration (which cover several programs or functions simultaneously) are the two most common kinds of indirect costs. They are often hard to estimate, However, as an organization’s management structure becomes more complex, it is often advisable to hire a public accounting firm to calculate an appropriate overhead rate. This rate can be applied as a percentage of the entire budget, and is especially useful when preparing or negotiating budgets with donors who may also not have considered some important indirect costs required for supporting an effective program. Step by Step: Preparing a Budget Budgeting needs to be as precise as possible. This means that a manager and his or her team should have all available information about the program, unit, or activity to be budgeted. When preparing a budget, some key assumptions are always made. For example, financial managers may assume that costs will remain relatively static during the period covered by the budget. Or it may be assumed that the funds available are adequate for program or organizational needs. Or planners may develop a budget and recognize that they must raise adequate funds before implementation. These scenarios fall under two basic budgeting techniques: zero-based budgeting (creation of an “ideal” budget before allocating available funds) and allocation budgeting (basing the budget on funds already allocated). STEP 1: Always begin by reviewing your plans – strategic, work, and operational. These plans will tell you what activities are scheduled, what resources (human, financial, and material) are needed, and when they must be available. Your budget and your formal plans must be absolutely synchronized. That is, no activity or staff should appear in the work plan that does not appear in the budget, and vice versa. STEP 2: Always have up-to-date cost figures. For example, have your organization’s Administrator or Human Resource Manager provide current salary and fringe benefits for all full- and part-time staff. If you are planning major purchases, get three pro-forma invoices from suppliers and select the one in which you have the most confidence. (This is not always the lowest invoice; some suppliers are unreliable or have hidden costs like shipping. Use your best judgement.) Ask your financial staff to conduct a “mini” audit of administrative costs over the last year; assume that they will increase by approximately 10-20%. Review what is happening to local currency. Is it losing or gaining value? Since most donors expect local budgets to be in local currency, it may be prudent to prepare your budget in a convertible currency (e.g., pounds sterling, dollars, Deutsche marks, yen, French francs). Then apply a conversion rate you think is rational and reflects currency inflation or deflation based on your experience over the last year or two. This is one way of avoiding shortfalls due to currency fluctuations. STEP 3: Always express your budget clearly so that anyone who is reading or working with it understands what you are trying to fund or achieve. Calculate line items in the following ways: ☛ For salaries and fringe benefits, calculate the line item 3 this way: N20,000/month x 12 months plus 15% of the total salary as employer payments towards pension as a fringe benefit: N20,000/month x 12 months x 0.15. ☛ For supervisory visits or travel for regularly scheduled meetings: Travel: N8,000 x 4 trips (1 trip/quarter) Per diem: N4,000/day x 3 days/trip x 4 trips ☛ For recurring administrative expenses: Bank charges: N1,000/month x 12 months x 2 accounts ☛ For education and training, don’t forget to calculate each line item based on the number of participants except for meeting rooms, resource persons, and equipment rental: ❐ Travel and per diem: N2,500 travel allowance x 50 participants Per diem: N 500/day for dinner and incidentals4 ❐ Materials: N1,000 x 50 participants ❐ Hotel (bed and breakfast): N4,000 x 50 participants x 6 days5 2 Adapted from The Manager, Winter 1999/2000 op. cit. For the purpose of this section, the currency being used is the Nigerian Nira. It is connoted by an “N.” 4 Often, at workshops, conference venues offer bed and breakfast, and lunch and teas are served to participants. Remember these possibilities when you are budgeting. 5 Often, conference planners want participants to arrive early to attend the start of the conference, workshop, or training. Always factor this indicating, for example, six days instead of five. 3 5 ☛ For purchased services (e.g., vehicle maintenance, audits, printing, construction if your organization is renovating), examine the contract and determine expected levels of service. For example, if your photocopier has a contract, you can choose to make the line item an annual figure or break it down into monthly costs through dividing it by “12”. Sometimes monthly totals are easier to monitor and evaluate. STEP 4: Always make sure your math is correct. Now, with computerized spreadsheets, there are virtually no excuses for mathematical errors. Even if you are preparing your budget manually, make sure that one or two people – especially from your finance staff – review the budget for mathematical accuracy. Remember some of the “hidden” costs, especially overhead or indirect costs. Apply them to the budget as a separate line item after all costs and categories have been calculated to ensure that you apply the indirect cost rate to all your organization’s administration and activities. STEP 5: Always follow the guidelines or formats provided by donors. Nothing can be more disruptive – or perhaps disqualify your organization from receiving support – than choosing your own “approach” to budgeting. Donors often design their formats to provide crosscutting information about all of the organizations they support. Therefore, if you are not following the format, you may not be entered into their management information or monitoring systems. A good manager is able to interpret his or her normal financial management or budgeting categories in line with those of donors. 6 Below, coverage or contents of some standard budget categories are suggested but you must conform to donor guidelines in order to raise funds. For successful organizations with multiple donors, it may be useful to have a donors coordination meeting. There, donors, management, and staff can discuss harmonizing some of the varying donor requirements to reduce the burdens caused by complying with multiple, and varying, formats, requirements, and stipulations. Many donors appreciate this pro-active initiative. Tips and Tools…Some Standard Budget Categories Although it may seem redundant because donor requirements often appear to be paramount, it is helpful for an effective manager to be familiar with budget categories and their corresponding activities or line items. The following are some suggested budget categories that can – and should – be modified based on your type of organization and programs. You may also find that there are several additional routine or recurring items that should appear under each category. You should discuss, with your program and financial staff sitting together as a team, what line items you might add . These categories also may help your finance staff prepare a detailed Chart of Accounts, an important tool for monitoring and segregating costs and keeping accurate records. A chart of accounts is a listing of all accounts (e.g., types of assets, liabilities, income, and expenses) that an organization is monitoring. It is listed in order of importance, and grouped by category and sub-category. Each account is given a code number and description. The coding should not be complex, but should provide enough information to make financial decisions. Some organizations key their chart of accounts to their major budget categories. Budget Categories Line Items or Category Coverage Salaries and Wages Gross salaries and wages paid to full- or part-time employees (including field staff or community-based workers). These must be supported by time sheets signed by the employee and his or her immediate supervisor. Insurance, retirement and health schemes, allowances, pensions, and all other benefits required by law (e.g., severance, P.A.Y.E., and gratuities such as 13th month). These benefits are usually paid only for bona fide employees, not consultants, volunteers, or seasonal workers. These are fees for services paid to professionals such as consultants, trainers, lawyers, editors, resource persons or other contractual, temporary personnel such as temporary office and accounting staff. Honoraria can also be paid to persons rendering a special service, e.g., providing a presentation or entertainment. Some organizations give Board members honoraria for heading or serving on special committees. All office-related expenses needed to keep an organization running such as postage, telephone, fax, e-mail, bank charges, utilities, photocopying, mail (including courier mail like DHL or shipping), staff recruitment costs, and subscriptions. Supervisory travel, field visits and staff meetings, fuel costs, local travel costs (e.g., bus fare, train tickets, taxis), shortterm car rentals, mileage reimbursements for use of private vehicles, air tickets and per diem. Note: It is better not to include travel costs connected with education or training here. Office supplies, clinic supplies, office furniture and equipment, computers, printers, and software, bicycles, motor cycles, and vehicles, cleaning supplies, supplies for community-based workers (e.g., bags, badges, uniforms, gum boots, umbrellas, diaries or registers). Note: Create a register or inventory for all non-expendables (i.e., assets that do not deplete such as a vehicle). Benefits Fees and Honoraria General Administration Travel and Associated Expenses Supplies and Equipment 7 Budget Categories Education and Training Purchased Services Line Items or Category Coverage Costs of travel (including local travel by bus or taxi as well as international travel, as appropriate, including visas) and per diem to all participants, trainers, and staff attending the conference, workshop or seminar. Cost of venue (meeting rooms and lodging), equipment rental, training materials, tuition and/or registration fees, shared meals (e.g., tea breaks and lunches), special events (e.g., opening reception or honoring special guests). Office, clinic or facility rental, equipment and car leases, office, clinic, equipment, and vehicle maintenance or repairs (including those under contract), data processing, storage, legal or audit fees, office or clinic renovation or partitioning, printing, advertising or promotion, fees to Internet or web site carriers. Monitoring Your Budget 8 Effective managers, after preparing a budget, must monitor it and determine whether or not assumptions on which it was based were reasonable and the resources needed are available. The budget should be reviewed on a monthly basis, concurrent with a review of the income and expense report or spreadsheet. A manager’s role in the review process is key: if some categories or line items are being underspent or overspent, the manager must investigate and seek clarification. Then the manager must decide on the best course of action: reallocate the budget (generally, donors expect to give advance approval for major reallocations), raise more funds, or stay on course, allowing the budget to remain as is. For an effective manager, inaction is not an option. Maintaining Good Cash Flow Although an effective manager need not be a financial expert, in order to make sound management decisions, he or she must be familiar with basic accounting. For example, your organization should decide what financial accounting method or system it will use.6 There are two principal methods of financial accounting: cash basis accounting and accrual basis accounting. Whatever method is used, all ledgers, financial records, and reports should use the same method. Some analysts prefer the accrual method because it gives a more accurate picture of an organization’s cash position and overall fiscal health. Many donors, however, prefer the cash basis because it is simpler to understand and manage. This is one time when program and financial managers should seek expert advice and weigh the pros and cons of choosing one method over the other, assist the organization to set up its financial management system, ledgers, and charts of accounts, and develop “user-friendly” tools and mechanisms for systems monitoring and updating. 6 Some analysts distinguish between financial accounting and managerial accounting. Financial accounting generally refers to the system used to record all financial transactions. Managerial accounting refers to the way in which costs are determined. Remember...There are two main types of accounting systems Cash Basis Accounting Accrual Basis Accounting Cash basis accounting is the most simple: revenue is recorded when received and expenses recorded when paid. However, it can distort the true cash position of an organization because income may not be related to the appropriate expenses, or payments can be manipulated to make an organization look more “cash rich” (e.g., delay in paying bills so the balance sheet looks better). Under accrual basis accounting, revenue is recorded when earned and expenses are recorded when incurred without regard to when cash changes hands. For example, if an organization prepays its rent annually, it is “expensed” in the ledger on a monthly basis although it was paid earlier. Similarly, an accrual system spreads depreciation equally over the useful life on an asset. In the accrual system, two ledgers are maintained: Accounts Receivable and Accounts Payable. These are updated as income is actually received or payments are actually made. Exercise…Using a format to facilitate budget monitoring This format can be used to facilitate budget monitoring and review. A prudent manager may request that financial staff institutionalize it and fill it in on a monthly basis. Format review can be a major agenda item at regular staff meetings. 9 Date [Chart of Accounts] Ref Code Cost Category Sites/Clinics(if applicable) Project Name Description BUDGET PERFORMANCE MONITORING FORMAT Budget Approved 10 Expenditure Balance Budget Remarks As mentioned earlier, a manager must monitor several kinds of costs. Among these are direct versus indirect costs or fixed versus variable costs. An example of a direct cost is payment to a trainer or for a venue for conducting a training course. An example of an indirect cost may be headquarters rent or the assistance of a financial officer, because both must cover the entire operations of an organization and cannot be specifically attributed to one project or program. Most managers are able to easily quantify direct costs because they are specific. Yet, indirect costs often contribute substantially to administration and management. Therefore, financial staff should be encouraged to determine the indirect costs – or the cost of doing business – for the organization. Usually, an accounting firm can provide the appropriate technical support to determine the indirect costs and express it as an average rate, or percentage, of normal operational costs. The indirect rate can then be included in budgets submitted to donors or in projecting annual operating costs. An example of fixed costs are those in a contract that specifies a monthly charge for a particular service. On an annual basis, staff salaries are generally a fixed cost (the term “generally” is used because it may be that a staff member receives a promotion or an increment as an incentive during a year). Variable costs are those that may depend on market forces or fluctuations. A simple example is the costs of stationery and information technology that may increase, or even decrease, based on demand, currency fluctuations, and the costs of production. Exercise…Identifying the types of costs your organization incurs 11 Sometimes, financial terminology seems confusing or overly theoretical. Sitting together with your financial and program staff, conduct a simple exercise that can help everyone to better understand these terms. 1. Divide a piece of paper into four sections. 2. Label each quarter as follows: at the top of the page, write “direct” in one quarter and “indirect” in the other. Do the same thing at the bottom of the page, writing “ fixed” in the first quarter and “variable” in the other. 3. Brainstorm about your organization’s routine expenses that fall into each category. 4. Note those expenses that may fall into more than one category. Are your systems capable of monitoring and providing accurate data on all of these categories? Are there linkages or patterns among them that suggest the need to monitor some categories simultaneously? 5. How do these categories compare with your organization’s chart of accounts? Do you need more or different categories to capture all the financial data you are monitoring? Variances If you are carefully and systematically monitoring your budget, you will discern income and expenditure patterns that must be watched carefully. Among the most critical are variances; that is, the difference between what was planned and the actual results. A manager must act when variances appear. Managers should ask questions, conduct a variance analysis (see below) and adopt a plan of action for addressing the variance. A variance is not always negative. For example, an organization may generate more income or attract more donor support than was originally assumed in designing the budget. Alternatively, an organization may receive an inkind donation, such as a building, eliminating the need to rent or renovate a facility. Most often, however, a variance involves a shortfall or miscalculation that must be addressed in order to ensure smooth operations. Remember…Conduct a variance analysis when results differ from plans.7 There are three primary types of variance analyses: ✔ Comparison of budgeted costs and actual costs or expenditures. ✔ Comparison of the planned quantity of an activity or purchase with the actual quantity. ✔ Comparison of the planned output with the actual output. 12 As a manager, when you realize there is a variance, ask questions and act. Bring in your program and finance directors, or your accountant, to analyze the situation. Then, decide upon and implement a concrete plan of action. Vexing Financial Management Issues Some recurring financial transactions can truly influence the “bottom line” and complicate financial management. Among these are travel advances, petty cash, income or revenue generated, requisition or procurement of goods and services, contraceptives and inventories of supplies or non-expendable assets. Each will be discussed separately. Travel Expenses Program managers, staff members, volunteers or Board members, and even program participants travel in furtherance of organizational programs, goals, and strategic objectives. Travel expenses are often among the most troubling and difficult aspects of controlling an organization’s budget and expenditures. Following are a few simple rules that, if implemented, can reduce these problems: h Always insist that a supervisor or manager approve travel before funds are allocated and the trip is taken. The Travel Authorization Form in Annex B is designed to facilitate the approval process. 7 The Manager. “Understanding and Using Financial Management Systems to Make Decisions, “ op. cit. h Always make sure that the travel is included in the budget. Very often, a staff person will want to make a “spot check” or emergency trip that was not budgeted. This does not mean that travel should be summarily denied. It does mean that if the trip is not included in the budget, its importance should be determined and funds reallocated. h Always insist that the travel advance is retired or liquidated before new funds are released to the traveler. A good rule of thumb is that the travel expense report (see Annex B) should be submitted within 10 days of the travelers’ return. Sometimes, travelers have back-to-back trips and it is difficult to prepare and submit the form. In any case, no traveler should take more than two trips without submitting a complete, and approved, travel expense report. h Always set rules for documentation of travel expenses. Receipts for lodging and transportation should be appended to the travel expense report. Receipts should be attached to document any other major expenses (visas, airport taxes, communication, local transportation, business meals, photocopying or faxing, car rentals, etc.). Generally, it is acceptable to set a threshold amount (i.e., the equivalent of $10-20) below which a receipt is not required. h Always ask the traveler to prepare a trip report so that you as a manager have additional documentation of the trip and expenditures. If the purpose of the trip was to prepare a major document (e.g., an assessment or curriculum), it may be produced in lieu of a trip report. A good trip report will give you clues about program performance and potential resource shortfalls, needs, or opportunities. With regard to travel, clear rules and regulations are extremely important and they must be communicated to all staff persons or others who are traveling. Procedures regarding accounting for travel should also be included in employee handbooks or personnel policies. Petty Cash Petty cash is just what it says: “petty.” In other words, petty cash is not a slush fund or a source for large payments. Petty cash is a small amount of money and should be used for minor expenditures. A staff member should request reimbursement from petty cash if the expenditure is ordinary and reasonable, and within the scope of the staff member’s duties (e.g., taking a taxi to deliver a document, staying late and taking a taxi home to comply with a deadline, paying for small-scale outside color photocopying, etc.). Some organizations use imprests as a supplement to the petty cash system (e.g., giving a clinic in-charge a small amount of money to replace expendable supplies such as Jik, gauze, bandages, soap, and gloves). Usually it is prudent to require prior supervisors’ approval before undertaking any activity for which petty cash or an imprest will be required. In any case, all petty cash or imprests must be reimbursed only upon production of original receipts. It is advisable to keep a simple petty cash or imprest book. Annex C contains examples of petty cash ledgers and vouchers. With both systems, all accounts should be reconciled on a weekly or bi-weekly basis since the amounts are small but critical to smooth operations. A monthly petty cash or imprest report should be included in the overall income and expenditure statement. 13 NOTE: Petty cash should always be kept under lock and key, and a specified administration or finance staff member should be responsible for the entire system, including reimbursements, keeping the records, and reconciling the books. Process Points…What Does Petty Cash Cover? Petty cash coverage may vary based on your organization’s mission or the way in which you obtain services and supplies. Items that are sometimes paid with petty cash are: Transport: Bus fares, taxis, repairing bicycle punctures, petrol (but not for long trips) Communication: Stamps, use of cyber-cafes to send email, calls from a public telephone (also specialized or small-scale photocopying) Cleaning needs: Soap, detergent, bleach, antiseptic, mops, floor or furniture polish Office needs: Paper, envelopes, pens, glue, string, adhesive tape, pins, staples, labels (only if there is a shortage. An organization should order on a quarterly basis to be more costeffective through volume discounts) Sundries: Matches, candles, paraffin, tea, sugar, milk, emergency supplies 14 Income Generation For most organizations, generating income is a bonus. It is an important step towards sustainability and lends flexibility in undertaking new initiatives and allocating resources. In Series 3 of this Manual, issues related to income generation and sustainability are discussed in detail. However, it is probably a good idea to set rules for monitoring and accounting for income generated by an organization. First, it is useful to open a separate account for income or revenue that is generated. Not only is this procedure an easy way to segregate donor funds from those independently raised by an organization, it is often a donor or legal requirement. Second, it is important to explain, in detail, how income will be generated as part of your program proposal, strategic, marketing, or business plan, and in your regular financial reports. Some of the critical details include methods of generating income, price per unit, source and amount of financial inputs from the organization (e.g., commodities, fees for services, membership cards, per trainee cost for a training course, etc.), and profitability ratios (e.g., the profit or revenue divided by the financial inputs). For some NGOs offering specific services, such as health services, it is useful to have a cash book or ledger to record cash collections, income generated by fees, and purchases. As a manager, you should shorten the intervals for collecting and accounting for cash as much as possible. For example, for nearby facilities, a weekly cash collection and report is advisable. Similarly, whenever commodities and supplies are distributed, they are the same as “cash.” Therefore, these distributions should also be entered into a ledger and kept as a form of inventory. Annex D contains sample formats or ledger sheets for cash collections and contraceptive receipt or distribution. Non-health organizations can adapt these formats to reflect their primary products or mission, such as IEC materials or agricultural and environmental protection input kits. Procurement Although it appears to be a simple matter, procurement of goods and services is often a major stumbling block for even a well-run organization. Procurement is an area requiring very specific, written procedures and guidelines. Procurement procedures are very often linked to financial control procedures to prevent fraud or waste of organizational resources. Clearly, procurements are tied to the budget, and the larger the expenditure, the greater the need for control. Procurement ranges from the routine, day-to-day acquisition of supplies to tenders for large- scale supply orders or long-term services. The stages in the procurement process should be the same no matter what is being ordered: h Managers should make sure that funds are available for procurement. h A strict process should be followed – with specific criteria for evaluating pro-forma invoices or responses to tender offers – that ensures the organization gets the best value for its expenditures, or the best qualified vendor. h Finally, a clear paper trail should be created so that an organization’s decision-making process is documented and defensible. 15 Keys to an Effective Procurement Process Step 1: Examine the budget. Ask yourself: are funds allocated for this specific expenditure? Are the costs or expenditures allowable? Step 2: Complete a requisition form for the expenditure (See Annex E). Step 3: Solicit at least three bids or quotations from different sources for the goods or services you are seeking. Attach them to the requisition form or send a separate memorandum describing the procurement and your choice of vendor or contractor. Sometimes an organization tenders when it needs a large amount of a specific commodity or a continuous service over a longer period. In that case, the bidding process should be competitive, with written media advertisements, selection criteria, and review of each respective bid before selection. A successful bid is one that demonstrates reasonable cost and ability to meet contractual terms. A successful bid is not always the lowest one. Step 4: Ask that a Local Purchase Order (LPO) be issued based on your selection through Steps 1-3. Usually, a staff member in finance and administration is in charge of, and should be able to provide guidelines to assist with, the process. (See Annex E for a sample LPO.) LPOs are very important documents and should be printed with sequential numbers to make them easy to track. Some organizations buy or print LPO books for this reason. Step 5: Issue the LPO to the vendor, contractor, or supplier. The LPO should be specific as to quantity, quality, time period for delivery, special requests (e.g., laminated paper, binders, tabs, size), and location for delivery. Each vendor should be instructed that the LPO is only the request for delivery. A vendor should provide a final invoice and delivery note before expecting payment. Copies of the LPO and delivery note should be attached to any request for payment submitted to the financial or administrative staff. 16 Inventories Some managers focus on cash transactions and forget that some of their other property or fixed assets must also be monitored. This is especially true for health or other programs that have a substantial turnover of supplies and commodities, including contraceptives. Generally, fixed assets are also non-expendable properties – that is, they have a useful life of more than two years. They should be insured and kept on a regular schedule for maintenance. Commodities and supplies (office, clinic, training, art or printing) are usually expendable supplies. They must also be monitored and replenished regularly to ensure their availability. Certain rules apply for both expendable supplies and non-expendable equipment. For example, inventory records should be kept for both kinds of items. A physical inventory should be conducted on a regular basis (quarterly, semi-annually, or annually) and the organization’s records with regard to stock should be updated. In fact, the records can serve as a checklist so that no item is overlooked in the inventory. The forms in Annex D can also be used as inventory formats to be adapted for your specific use. Some tips about expendable supplies and contraceptives: Expendable supplies should be: ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Stored in a clean, well lighted, well ventilated area. Kept off the floor on shelves or palettes. Logged in based on a FEFO system, that is First Expired, First Out. Kept in a locked area to which only authorized personnel have access. Kept on separate register pages or on cards to facilitate stock taking and inventories. Accounted and signed for by all staff who receive them. Formats should be developed for this purpose. 17 Instituting Effective Financial Controls This is among the most challenging aspects of financial management for the manager and financial professional alike. This is, in part, because financial controls are essentially rules, policies, and procedures that must be consistently applied, adhered to, and enforced. Management’s attitude toward controls – that is, whether management promotes an environment in which controls are valued or is lax in their enforcement – can make a significant difference in the effectiveness of an organization’s financial management. Control policies and procedures are designed primarily to: h Ensure that accounting records are complete and accurate. h Institute safeguards, checks, and balances so that expenditures are properly approved and made as budgeted. h Safeguard assets and curtail misappropriation or theft. h Prevent and detect fraud and errors. h Protect staff. h Ensure proper utilization of resources. h Support the preparation of reliable and timely financial reports. Control procedures generally involve some comparisons of information from different sources to verify and validate requests, expenditures, and reports. Usually, organizations have three kinds of control procedures: accounting controls, segregation of duties, and managerial supervision. Accounting controls Accounting controls are usually maintained by the financial management staff and involve comparisons between data sources to verify the accuracy of transactions and recording. Some of the comparisons8 that should routinely be conducted include: h Comparing cash receipts as recorded by a cashier or cash clerk with information on the numbers of patients or clients recorded in a register or ledger. h Comparing total receipts with the amount deposited in the bank. h Counting cash to verify that the cash on hand agrees with the cash balance recorded in 18 the cash book. h Reconciling bank statements to compare cash book entries with entries in the bank statement. h Controlling stock inventory by comparing the physical stock with the accounting records or stock cards. h Comparing actual expenditures and revenues with budgets. Any variances or discrepancies should be immediately documented and reported to senior management. Senior managers should undertake a review of the circumstances and any action needed, being fair, but firm. Segregation of duties The concept is simple, but its applications are often difficult. Basically, segregation of duties means that one person should never be responsible for all aspects of a transaction. In other words, one person checks the work of another. For example, one person should not order or make a requisition for purchase, review the pro forma invoices, approve the selection of the vendor, and sign the check for payment. Also, the person who keeps cash should not maintain the cash book or do bank reconciliations. The person who prepares the payroll should not pay salaries, while the person who makes payments should not approve them. Three important financial management functions that should routinely be handled by different people are: h Custody – physical responsibility for cash, stores, commodities, vehicles, major equipment, etc. h Recording – making entries into the main accounts or ledgers from which reports are made. h Authorizing – approving purchases and other uses of resources. 8 Based on materials from Abt Associates, Bethesda, MD, Cambridge, MA and Johannesburg, RSA. Managerial supervision An effective manager will ensure that staff members at all levels and members of the Board understand an organization’s internal controls, policies, and procedures. He or she will insist on written policies and procedures, and regularly review controls for currency and effectiveness. The manager should also not circumvent or ignore controls or problems that they uncover. Most important, an effective manager should be a model of compliance. In fact, he or she should be a primary advocate, adhering to sytems disciplines, reviewing reports systematically, and asking questions about any discrepancies or ambiguities. Annex F contains some very useful checklists, prepared by Abt Associates, to monitor internal controls and their effectiveness. Remember…There are some “Thou Shalt Nots…” Here are some simple principles for maintaining internal controls. ✔ Thou shalt not have a financial management system without written procedures that are regularly reviewed and updated. ✔ Thou shalt not enter into transactions without supporting documentation such as original receipts, invoices, LPOs, and internal approval documents (e.g., requisitions, travel authorization forms). ✔ Thou shalt not leave cash and checkbooks unsecured. A few specific persons should be given the responsibility for maintaining secure physical custody of these items. ✔ Thou shalt not manage an entire transaction without cross-checking by another person. ✔ Thou shalt not forget to thoroughly review requests for approval and financial reports as received and to ask about any variances between the budget or prior reports and the current requests or reports. ✔ Thou shalt not ignore evidence of abuse of physical assets such as vehicles or major equipment. Reporting on Your Organization’s Finances Reporting on an organization’s finances generally takes two forms: reports needed for sound internal financial management, controls, and decision-making and reports required by external donors (See Annex G “Grantee Financial Report”). Both are extremely important, but often managers focus more on the external than the internal reports. Yet, the internal reporting system may be even more critical because it will help a manager avoid small problems becoming major ones. Organizations must conduct an annual audit, both for their own internal fiscal discipline and also to comply with donor requirements. Audit results will provide important insights into areas of successful financial management, or areas needing improvement. Although most 19 financial reports required by donors are formatted, it is often useful to provide a more detailed narrative to explain some of the financial issues or changes that have occurred since preparing the budget or the first report. The audit report may provide useful information for this purpose. Annex G also contains a good internal report format such as an income and expenditures statement. This sample is manually prepared but the advent of spreadsheets or software applications means that a manager should be able to receive accurate and timely reports at a monthly interval. A manager should also provide regular (at least quarterly) reports to an organization’s Board to inform them about the organization’s cash position and needs. If the Board has a Finance Committee, a prudent manager will engage them in reviewing financial data, making forecasts of potential revenues or shortfalls, and identifying new donors. Internal monthly financial reports can be issued with any frequency or combined in any configuration required by donors: quarterly, semi-annually, or annually. A prudent manager, however, will ask for internal biweekly or monthly reports as a matter of course. Frequent reports help monitor and protect against downturns in the organization’s fiscal health. Sometimes, donors ask that key data and information be appended to the financial report. Data may include copies of bank statements and bank reconciliation exercises; lists of salaries and benefits paid from donor funds; acknowledgement of contraceptives or other supplies received; reports on the currency exchange rates over a period; and a list of unpaid obligations for the period covered by the report. Whatever the stipulations, follow the donors’ guidelines. If there are no guidelines, you may wish to review Annex G for a model financial report. 20 Bright Idea… Avoid some of these managerial pit-falls:9 ✔ Chronic crisis management, leading to last-minute, often more expensive, solutions that contribute to inefficient management and missed opportunities. ✔ Unrealistic price setting that may create a situation in which an organization cannot recover its costs or incurs greater losses. ✔ Inaccurate analyses of the real cost of doing business, such as a failure to consider fixed or indirect costs when preparing budgets or forecasting resource needs. ✔ Dependency on a single funding source or donor, which leaves the organization vulnerable if the donor reduces or suspends funding. ✔ Failure to react to environmental changes that can lead to missed opportunities to generate or attract new funding or failure to budget for new regulatory or other requirements (e.g., licenses). ✔ Lack of managerial skill in analyzing, using, and communicating financial information such that a manager is unable to recognize potential risks or make appropriate decisions about the use of scarce resources or the generation of new ones. 9 Adapted from The Manager, op. cit. Annex A Model Budget Formats 21 Financial Management Module v. 1 Family Welfare & Counseling Center, Nyeri, Kenya Period - January 2001 to December 2001 LOCAL COSTS KSHS $ SALARIES AND WAGES Project Director (20% time) @ Kshs.3,450/mon x 12 mos 41,400 591 66,240 946 2 each @ Kshs.1,380/mon x12 mos x 2 33,120 473 1 Clinical cytologist @ Kshs 1,380/mo x12 mos 16,560 237 Project Accountant (at 20% time) @ Kshs 2,760/mon x12 mos 33,120 473 Project Accounts Assistant @ Kshs 575/mo x12 mos 6,900 99 132,480 1,893 @ Kshs. 552/mon x 12 mos x 60 397,440 5,678 17 Depot holders/Senior housekeepers @ Kshs 345/mon x 12 mons x 17 70,380 1,005 2 Project Coordinators (40% time) 2 each @ Kshs.2,760/mon x12 mons 2 Project Assistants (each at 50% time) 10 Hall Wardens @ Kshs.1104/mon x 12 mos x10 60 Peer Counsellors Sub-total, Salaries & Wages 817,640 11,395 FEES and HONORARIA 6 external facilitators to conduct initial and refresher training courses for new and old peer counselors and depot holders @ Kshs 10,000/week x six weeks 60,000 857 GENERAL ADMINISTRATION Stationery and Office Supplies @ Kshs.6000x12 mons 72,000 1,029 Telephone @ Kshs.2,500/mon x 12 mos 30,000 429 Bank Charges @ Kshs.1,500/mon x 12 mos 18,000 257 Postage, fax @ Kshs.3,000/mon x12 mos 36,000 514 Financial Management Module v. 1 LOCAL COSTS KSHS $ Photocopying @ Kshs.6,000/mon x 12 mos 72,000 1,029 Computer stationery @ Kshs.5,000/mon x 12 mos 60,000 857 288,000 4,114 @ Kshs.20 per km x 400 km/mo x12 mos using university vehicle 96,000 1,371 Outreach for peer counsellors by public means @Kshs.1500x12mon 18,000 257 114,000 1,629 Pap smear Reagents (Haemotoxylin,E.A36,O.gg Carbowax) 100,000 1,429 30 video cassettes @ Kshs.400 each (VHS-240) 12,000 171 Dubbing 30 cassettes at @ Kshs.150 each 4,500 64 Power Stablizer 7,000 100 150 T-Shirts @ Kshs.400 x 150 60,000 857 One Compaq Deskpro 450 MHZ computer 136,290 1,947 One HP printer base 1100 40,280 575 One APC UPC 500 VA 14,440 206 50 badges @ Kshs.150 x 50 7,500 107 One Sterilizer Medium size @ Kshs.15,000 15,000 214 15 Condom dispensers @Kshs.1,000x15 15,000 214 412,010 5,886 Sub-total, General Management TRAVEL AND ASSOCIATED EXPENSES Fuel for project-related travel using public vehicle Sub-total, Travel & Associated Expenses SUPPLIES AND EQUIPMENT Sub-total, Supplies and Equipment Financial Management Module v. 1 LOCAL COSTS KSHS $ PURCHASED SERVICES 1,000 FLE Magazines ("KU Peer")/semester x 2 semester @ Kshs.100 each x 1,000 x 2 74,000 1,057 Insurance of Project equipment @ Kshs.10,000 per year 10,000 143 Maintenance of Project equipment @ Kshs.10, 000 per year 10,000 143 48,000 686 30,000 429 172,000 2,457 40,000 571 481,000 6,871 11,100 159 30,000 429 Transport and lunch allowance for 2 internal facilitators @ Kshs.1,000 per day x 5 days 10,000 143 23 old peer counselors meals & Accom. @ Kshs.1,000X 6daysX23 Stationery for 23 new peer counselors @ Kshs.300x23 138,000 6,900 1,971 99 Hiring of hall facilities @ Kshs. 1,500/day x 5 day 7,500 107 Transport and lunch allowance for 2 internal facilitators @ Kshs.1,000 per day x 5 days Meals for 17 depot holders @ Kshs.500xl7x5 days 10,000 42,500 143 607 Stationery for 17 depot holders @ Kshs.300xl7 5,100 73 Secretarial Services @Kshs.4,000/mon x 12 mos Life Planning Skills orientation package @ Kshs. 200 x 150packages Sub-total, Purchased Services EDUCATION AND TRAINING 10 days initial training for new peer counselors Transport and lunch allowance for 2 internal facilitators @ Kshs.1,000 per day x 10 days x 2 facilitators X 2 sessions Two back to back sessions to be conducted for 37 new peer counselors Meals & accom for the 37 new peer counselors @ Kshs.1,000X13 daysX37 Stationery for 37 new peer counselors @ Kshs.300x37 Hiring of hall facilities @ Kshs. 1,500/day x 10 day X 2 session 5 days refresher training for old peer counselors 5 days refresher training for depot holders Financial Management Module v. 1 LOCAL COSTS KSHS $ Hiring of hall facilities @ Kshs. 1,500/day x 5 day 7,500 107 Basic computer training for 60 students @Kshs 4,000/student x 60 200,000 2,857 1 day Chairmen & Dean s update Workshop for 35 persons Stationery @ Kshs. 500/person x 20 persons Lunch for 35 persons @ Kshs. 2,000/person/day 10,000 70,000 143 1,000 Sub-total, Education and Training 1,069,600 15,280 TOTAL LOCAL COSTS 3,033,250 43,332 General Administration Travel and Associated Expenses Supplies and Equipment Purchased Services 977,640 288,000 114,000 412,010 172,000 13,966 4,114 1,629 5,886 2,457 Education and Training 1,069,600 15,280 3,033,250 43,332 x 35 persons x 1 day Budget Summary Fees and Honoraria TOTAL LOCAL COSTS Exchange rate (US$) = Kshs 70 Additional funding US$ equivalent = $20,000 Total Local Cost Yr 2 Budget for KU = $17,852 Balance of funding b/fwd Yr 1 = $5,486 TOTAL FUNDING = $ 43,338 Financial Management Module v. 1 Sample B: Cash Flow Budget for AFYA Clinic 10 AFYA CLINIC AFYA CLINIC CASH FLOW BUDGET FOR THE 5 MONTHS ENDING MAY, 2001 (In Nira) January February March 400,450 (459,908) 251,734 Patient Fees -Inpatient 1,145,667 1,145,667 1,345,667 1,345,667 1,345,667 Patient Fees - Outpatient 2,750,100 2,750,100 2,950,100 2,950,100 2,950,100 Laboratory Fees 1,375,050 1,375,050 1,475,050 1,475,050 1,475,050 0 0 3,000,000 0 0 50,000 0 50,150 50,150 50,150 5,320,817 5,721,267 5,270,817 4,810,909 8,820,967 9,072,701 5,820,967 10,454,493 5,820,967 7,061,260 Salaries 3,279,175 3,275,175 3,279,175 3,579,200 3,576,200 Drugs/medical supplies 1,875,000 0 120,000 2,875,000 0 Building/equipment maintenance 125,000 125,000 125,000 125,000 125,000 Utilities 266,667 266,667 266,667 266,667 266,667 Administrative/office 301,166 301,166 301,166 301,166 301,166 0 0 0 1,500,000 0 Cash at start of month April May 4,643,526 1,240,293 Cash Receipts Donations Interest/Other Income Total Receipts Total Cash Available Payments expense Purchase of car Purchase of medical equipment Total Payments 0 250,000 0 0 0 6,181,175 4,559,1751 4,429,175 9,224,200 4,609,200 Cash at end of the month (459,908) 2551,734 4,643,526 1,240,293 2,452,060 10 Source: Abt Associates. Fundamentals of NGO Financial Sustainability, 2000. Annex B Travel Authorization and Expense Report Formats Travel Expense Report Project ______________ DATE: Travelor Office ___________________ ___________________ Page ______ of _______ Week Ending _________ Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Paid by Charged Traveler to Project From: Place To: Place Ticket (airplane, bus, train) Mileage Visa/Airport Tax Hotel/Lodging Per Diem Taxis Communication Other Previous page total: Purpose of travel___________________________________________________ All payments except per diem should be supported by documentation. I certify that the above are accurate: Grand total: Amount due project: Amount due travelor: Signature: _______________________________________ DATE: _________ Total Financial Management Module v. 1 Travel Authorization Request Form Name of Project _________________________________________ Traveler Type (Employee, Consultant, Trainee, Other) ___________ Purpose of Trip _________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ Travel Dates: From______________ To Itinerary: _____________ Date Departure Arrival Mode Estimated Per Diem ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ ___________________ ___________________ ___________________ ___________________ ___________________ ___________________ Travel Related Expenses: Total Advance Requested: ___________________ To be completed by the traveler and reviewed by the accountant: Have all expense reports been filed? Are all advances accounted for? ________Yes ________No ________Yes ________No Accurate and Approved: ___________________________ ___________ ___________________________ ___________ Traveler Date Department Head Date ___________________________ ___________ ___________________________ ___________ Project Manager Date Project Director Date Note: Any traveler with outstanding balances due from previous trips will not be approved for further travel. Annex C Petty Cash Vouchers and Ledgers Financial Management Module v. 1 Example: A simple petty-cash book Date Details Voucher Amount Received 1.4 2.4 3.4 8.4 11.4 To imprest (original funding) Stamps Bus fares Telegram Stamps Bicycle puncture Stationery 1 2 3 4 5 6 12.4 Kerosene 7 15.4 TOTAL 40.00 8.40 5.30 4.20 2.20 2.70 5.60 3.80 40.00 Balance 16.4 Paid out 32.20 7.80 Balance B/F 7.80 To imprest (replenishment) 32.20 Financial Management Module v. 1 Petty Cash Voucher No: 3466 Date:_______________ Purposes & Payment Amount Shs.____________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Received by: Checked by _______________________________ ___________________ Paid by___________________________________ Signature Annex D Cash Collection and Contraceptive Receipt/Distribution Formats Register for Non-Expendable Properties Name of Project ________________________________ Site ____________________________ Period Covered _______________ Date of Acquisition Description of Property Person completing format ____________________________ Cost Serial Number Location Condition Tag Number Remarks Contraceptive or Supplies Control Card Name of Project ________________________________ Site ____________________________ Period Covered _______________ Date Description Person completing format ____________________________ Ref # Received # Issued Balance on Hand Remarks Annex E Requisition Forms and Local Purchase Orders Financial Management Module v. 1 PURCHASE REQUISITION To: Finance and Administration FROM: Date: Please procure the following materials/services for my use: Quantity Estimated Unit Cost (Kshs.) Description/Supplier _______________________ Date _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ Checking/Approvals Department Head Procurement Officer Finance Director CEO/Ed LPO Number Date LPO Issued Estimated Total Cost (Kshs.) This form should be completed by the ultimate user of the materials/services. A properly completed and approved copy should be attached to the payment voucher. Financial Management Module v. 1 NAME OF PROJECT ________________________ PAYMENT REQUISITION/VOUCHER Bank account No. ________________________ Voucher No. ________________ Amount ________________________________ Date ________________ Check No. ______________________________ Cost category ________________ Payee ______________________________________________________________ Purpose ____________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ Payment requisitioned by ______________________________________________ Check received by ________________________ Date _______________________ Checked/approved by: Supporting documentation & other details attached/checked ____________________ Additions/calculations of attached documentation checked ____________________ Payment reviewed ____________________ Payment approved ____________________ COST CATEGORIES* 0000 Salaries & Wages 0000 Travel & Associated Expenses 0000 0000 0000 Benefits Fees/Honoraria General Administrative 0000 Supplies & Equipment 0000 Purchased Services 0000 Education & Training * Cost categories based on your organization's Chart of Accounts. Financial Management Module v. 1 LOCAL PURCHASE ORDER (LPO) Phone:________________ P.O. Box ______________ Fax:__________________ Date: _________________ To: ____________________________________________ From: __________________________________________ YOUR ORGANIZATION S NAME HERE ________________________________________________ Please supply the following goods: Qty Particulars NO. 6085 Signed: _____________________________ Quote above Order No. on all Invoices and Delivery Notes. Annex F Internal Questionnaires and Checklists Example: Internal Control Questionnaire for Cash Management Answer Yes Question 1. Is the accounting department separate from the cashier? 2. Is there a ledger system of accounting? 3. Is the accounting system maintained by a trained bookkeeper and/or accountant? 4. Is there a safe location for cash deposits such as a bank or safe? 5. Does the facility deposit each day's receipts without delay? 6. Where is the deposit made (bank, safe, etc.)? 7. Are deposits made by someone other than the cashier or bookkeeper? 8. Does a responsible employee other than the cashier (depositor) investigate any cash taken out of the deposit location? 9. Are the cashier's duties segregated from the recording of the cash receipts or accounts receivable? 10. Does someone outside the cashier department make ledger entries? 11. Does someone other than the cashier handle the petty cash fund? 12. Does the cashier handle only one fund? If not, list others. 13. Is there a withdrawal co-signature authority process? 14. Does the cashier assume full responsibility for the receipts from the time they are received until the time they are handed over for the deposit? 15. Is the cash adequately safeguarded (physically) within the facility? Cash Receipts 1. Is an independent listing of cash receipts prepared before they are submitted to the cashier or bookkeeper? 2. Are cash receipts deposited intact each day? 3. When cash sales occur, are all receipts pre-numbered? 4. Are all receipts accounted for daily, and do they match with the cash collections? 5. Are duplicates of the deposit slips retained and reconciled to the corresponding amounts in the cash receipts records? 6. Does someone prepare a daily report of cash balances? 7. Is the bank deposit made by someone other than the cashier or bookkeeper? Methods 1. Are receipts recorded by cash registers or other mechanical device? No N/A 2. If so, are machine totals independently verified by those outside the area? 3. Does the facility use cash receipt books? 4. If so, are the receipts re-numbered? 5. Does a person other than the cashier independently check the numerical sequence and daily totals? 6. Are the receipts matched with the cash collections? 7. Are the unused receipt books properly safeguarded? 8. If none of the above is used, is an equivalent system used? Explain. 9. Do adequate controls exist to prevent misappropriation of cash by the cashier, for example, b fictitious discounts, waivers, allowances, etc.? Based on all of the information above, comment on the adequacy of internal control. For all weaknesses indicated, Originally reared by: Date: Reviewed in subsequent examination by: Date: Notes: Observation Example: General Control Environment Question Answer Yes No Observation N/A 1. Does the organization have an organizational chart? 2. Does the organization have a chart of accounts or an organized financial accounting system? 3. Are there accounting and internal control manuals, and do they set forth accounting procedures? 4. Does the organization have an internal auditor or equivalent person? 5. If there is an internal auditor, is he or she independent from the internal control processes? 6. If there is an internal auditor, are there internal audit reports available? Have they been reviewed recently? 7. Is the general accounting and bookkeeping department completely separate from the cash receipts and cash disbursement function? 8. Is the general accounting and bookkeeping department separate from the sales, purchasing, or operational departments? 9. Are expenses and costs under budgeted control? In other words, is there a budget plan to which others can compare performance? 10. Are key and material bookkeeping entries approved by senior management personnel? 11. Are periodic financial statements prepared and submitted to management? 12. If so, are they designed to alert management to significant fluctuations in costs, revenues, assets, etc.? 13. List the names of those employees who exercise the following functions. Are any of these functions performed by the same people? Accountant Bookkeeper Cashier Internal Auditor Purchasing Payroll Department Head Based on all of the information above, comment on the adequacy of internal control. For all weaknesses indicated, scommend corrective action to be taken. Update this checklist to monitor the effectiveness of the corrective action. Originally prepared by: __________________________________________ Date: ____________________ Reviewed in subsequent examination by: ____________________________ Date:____________________ Notes: Example:Internal Control Questionnaire: Payroll Answer Observation Yes No N/A Question 1. Are payroll duties effectively rotated? 2. Are vacations of payroll clerks enforced? 3. Are wage rates authorized in writing by the designated supervision manager? 4. Is the payroll double-checked as to the hours worded, rates, payroll deductions, and taxes? 5. If the payroll is delivered by check, are the checks re-numbered? 6. Are blank checks in a secure area? 7. Are the workers identified by their supervisors or other system for validating employment? 8. Are unclaimed wages relatively insignificant? 9. Are audits of the payroll system periodically made by outside "independent" auditors? 10. During disbursement of cash payrolls, is the area of disbursement secure? 11. Have payrolls stayed relatively steady in all departments, without hidden fluctuations? 12. Are payroll checks or cash disbursements only picked up by the employee? 13. Is the process for adding an employee to the payroll in control and done through cross-authorization procedures (with more than one manager's signature)? Based on all of the information above, comment on the adequacy of internal control.. For all weaknesses indicated, recommend corrective action to be taken. Update this checklist to monitor the effectiveness of the corrective action. Originally reared by: Date: Reviewed in subsequent examination by: Date: Notes: Example: Internal Control Questionnaire: Medical Inventories and Supplies Answer Question Yes No Observation N/A 1. Are the following items kept under the strict control of a few designated employees? Medicines? Bandages? Topical ointments? Gases? Disposable and reusable medical instruments such as syringes and needles? 2. If practical, are inventories recorded monthly in bookkeeping or other accounting records? 3. Are receipts for issuance made for withdrawal of inventories? 4. Are withdrawals allowed only under a specific system of designated authorizations? 5. Are adequate inventory levels maintained? 6. Are physical inventories taken at lest yearly (or periodically throughout the year)? 7. Is the inventory supervised by an independent manager or equivalent? 8. Is the merchandise labeled and classified properly? 9. During inventories of larger stores, are pre-numbered inventory tags or an equivalent system used? 10. Is an overall review periodically made of slow-moving or obsolete inventory? 11. Is adequate accounting control exercised over items kept in patient areas (e.g., near nursing areas)? 12. If periodic inventories are maintained, are they annually reconciled to actual amounts by means of a complete physical inventory? 13. Do all inventory records show quantities, unit costs, and aggregate values? 14. Are the inventory records maintained by and accessible to individuals other than those who have access to the inventory? 15. Are inventories maintained in more centralized storage areas (as opposed to being disbursed throughout the facility)? Based on all of the information above, comment on the adequacy of internal control. For all weaknesses indicated, recommend corrective action to be taken. Update this checklist to monitor the effectiveness of the corrective action. Originally reared by: Reviewed in subsequent examination by: Notes: Date: Date: Example: Internal Control Questionnaire: Purchase and Expense Management Answer Question 1. Does the organization have a purchasing department? 2. If so, is it independent of the accounting department? 3. Is it independent of the receiving department? Yes No Observation N/A 4. Are purchases made only after respective authorization signatures are made according to policy? 5. Are all significant purchases channeled through the purchasing department? 6. Are purchase order authorizations required of all significant purchases? 7. Do certain items et purchased through competitive bidding? 8. If so, is the review made of the bids independent and objective? 9. Are purchase prices thoroughly reviewed and checked by a knowledgeable employee? 10. At the time of receipt, are purchased quantities checked against actual receipt quantity? 11. Is the receiving department denied access to the purchasing records? 12. Does the receiving department fill out the receipt of goods documentation? 13. Are copies of the receiving reports sent to the accounting or bookkeeping department? (if not, how are accounting records updated?) 14. Are copies of the receiving reports sent to the purchasing department? (If not, how are purchasing orders reconciled to actual goods received? 15. When goods are returned to vendors, are credits obtained? 16. Do safeguards exist for the proper accounting of partial shipments being received against orders? 17. Does a responsible official approve payment of purchasing orders? 18. If purchases are paid directly out of cash, is the system for purchase authorization, inventory receipt, quantity verification, and cash disbursement authorization intact, independent of each other, and capable of being tracked)? Based on all of the information above, comment on the adequacy of internal control. For all weaknesses indicated, recommend corrective action to be taken. Update this checklist to monitor the effectiveness of the corrective action. Originally reared by: Reviewed in subsequent examination by: Notes: Date: Date: Example: Internal Control Questionnaire: Petty Cash Management Question Answer Observation Yes No N/A 1. 2. Are the cash slips re-numbered? Do different employees periodically take charge of the fund? 5. Is the amount of the petty cash fund small enough so as to make replenishment a frequent occurrence? Is there a maximum amount that may be drawn from the petty cash fund? If so, state the amount. Are receipts/vouchers maintained for each expense? 6. Do regulations prohibit the cashing of checks from the fund? 7. Does an independent and responsible employee reconcile the total vouchers with the remaining cash amounts before the fund is replenished? 8. Do the vouchers explain the nature of the expense? 9. Are the amounts written out in words on the vouchers? 3. 4. Does only the custodian of the petty cash fund have authorization to sign 10. receipts/vouchers and authorize disbursements? 11. Are there surprise checks of the the cash fund? Have steps been taken to address any past abuse of the petty cash 12. funds? Based on all of the information above, comment on the adequacy of internal control. For all weaknesses indicated, recommend corrective action to be taken. Update this checklist to monitor the effectiveness of the corrective action. Originally reared by: Date: Reviewed in subsequent examination by: Notes: Date: Annex G Model Financial Reports Financial Management Module v. 1 Grantee Financial Report (GFR) Project ID # ________________ Organization_______________________________ Project Title________________________________ Project Director_____________________________ Project Start Date ______________ Project End Date ______________ This project covers the following period: Period #______________ From _______ To _______ Section One: Status of Budget (Column 1) Budget Category Approved Budget Amounts (Column 2) Expenditures this Period (Column 3) Expenditures to Date Salaries Benefits its Fees/Honoraria General Administration Travel Supplies/Equipment Purchased Services Education/Training TOTAL Note: Organization must attach written explanation for any significant expenditures not included in the budget or any expenditures in excess of the budget. (Column 4) Balance of Budget Financial Management Module v. 1 Section Two: Status of Project Funds A. Balance on hand at the beginning of period ______________ B. Total local currency received during period ______________ C. Total foreign currency received during period ______________ Conversion rate to local currency ______________ (Attach bank advice) D. Total interest earned on project account (if any) ______________ E. Balance on hand at end of period ______________ F. Bank statement balance at end of period ______________ G. Difference (attach bank reconciliation) ______________ Section Three: Status of Program Income A. Did the program earn income during this period? ____Yes ____No* B. If yes, balance of income on hand at beginning of period ______________ C. Interest earned this period on income. ______________ D. Income spent during this period ______________ E. Balance on hand at end of period ______________ *Please briefly describe how the program earned income. Please attach a schedule of all persons paid from program funds during this period. I certify that all the information is correct and complete. Name: ____________________________ Title: ___________ Signature: _________________________ Date: ___________