Principles of OHS Law - The OHS Body of Knowledge

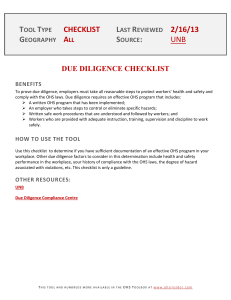

advertisement