Meeting Report - WHO Western Pacific Region

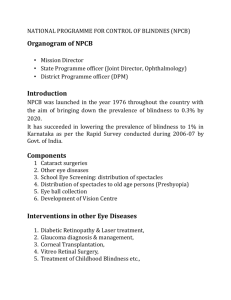

advertisement