Public Health Interventions - Applications for Public Health Nursing

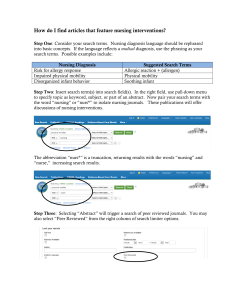

advertisement