Scandinavian Print Cultures 1450-1525: A Dissertation

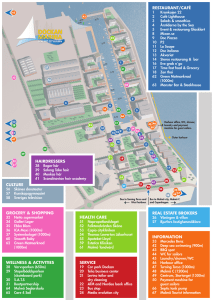

advertisement