A Doll's House - Auckland Theatre Company

advertisement

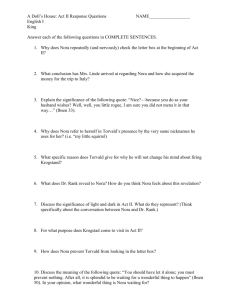

A DOLL’S HOUSE BY EMILY PERKINS ADAPTED FROM IBSEN'S ORIGINAL EDUCATION PACK CONTENTS PARTNERS A U C K L A N D T H E AT R E C O M PA N Y R E C E I V E S P R I N C I PA L A N D C O R E F U N D I N G F R O M : S U B S I D I S E D S C H O O L M AT I N E E S A R E M A D E P O S S I B L E BY A G R A N T F R O M Synopsis P.04 Set and Lighting Design P.20 About Henrik Ibsen P.06 Costume Design P.26 About Emily Perkins P.08 Resources and Readings P.28 Nora and Her Legacy P.10 ATC Education P.29 A Classic Adaptation P.12 Curriculum Links P.29 New DIrections P.16 ATC Education also thanks the ATC Patrons and the ATC Supporting Acts for their ongoing generosity. VENUE: Maidment Theatre, Alfred Street, Auckland City. PLEASE NOTE • Schools’ performances are followed by a Q&A Forum lasting for 20 – 30 minutes in the theatre immediately after the performance. • Eating and drinking in the auditorium is strictly prohibited. • Please make sure all cell phones are turned off prior to the performance and, if possible, please don’t bring school bags to the theatre. • Photography or recording of any kind is STRICTLY PROHIBITED. SCHOOL MATINEE PERFORMANCES: Thursday 14 and Thursday 21 May at 11am. RUNNING TIME: 100 minutes without an interval. SUITABILITY: This production is especially suitable for Year Levels 12 and 13. ADVISORY: Contains frequent use of strong language and adult sexual themes. 01 1 CAST Nora Helmer — LAUREL DEVENIE Theo Helmer — DAMIEN AVERY Christine Linde — NICOLA KAWANA Aidan — PAUL GLOVER Gerry — PETER ELLIOTT Billy — ZACHARY COX / CASSIDY SCOONES Bee — MADELEINE WALKER / EMILY ARCHER CREATIVE Director — COLIN McCOLL Dramaturg — PHILIPPA CAMPBELL Set Designer & Lighting Designer — TONY RABBIT Sound Designer — JOHN GIBSON Costume Designer — NIC SMILLIE PRODUCTION Production Manager — ANDREW MALMO Acting Company Manager — ELAINE WALSH Technical Manager — KATE BURTON Stage Manager — ELIZA JOSEPHSON-RUTTER Chaperone — VIRGINIA FRANKOVICH Technical Operator — ROCHELLE BOND Sound Effects Programmer — THOMAS PRESS Props Master — NATASHA PEARL Wardrobe Assistant — PENELOPE PRATT Set Construction — 2CONSTRUCT Production Intern — NICOLE ARROW EDUCATION PACK CREDITS Editor — LYNNE CARDY Writer — AMBER MCWILLIAMS Design images — courtesy of TONY RABBIT and NIC SMILLIE Production Images — MICHAEL SMITH Design — SAUCY HOT DESIGN SCHOOL WORKSHOP TEAM Director — JANE YONGE Actor/Facilitator — VIRGINIA FRANKOVICH Actor/Facilitator — JADE DANIELS 2 02 03 SYNOPSIS Christmas Eve. Theo receives news that he has just won a big new contract to build an eco-village. His wife Nora is excited and full of plans; he tells her to settle down, and then goes back to work. She wakes the children to have someone to celebrate with. Theo’s old friend Christine turns up unexpectedly and finds Nora at home. The women discuss Christine’s divorce and the tough economic times. Christine makes some remarks about Nora’s house, husband and history that suggest she is jealous of Nora’s ‘charmed life’. Nora reveals that all is not as rosy as it seems: without telling Theo, she has borrowed lots of money to underpin their business, and is paying it off on her own. She also tells Christine about the contract. Christine asks Nora to find out if Theo can give her (Christine) a job as site manager, and Nora agrees. Theo comes in: Nora suggests the job, to Christine’s embarrassment, but Theo agrees. An unexpected guest, Aidan, arrives. Theo and Nora pretend that they are just heading out to their neighbours’ party – it is Aidan who has lent Nora the money. Theo 04 goes to the party. Nora tells Aidan she will repay her debt in January, and says Theo’s got a big contract. Aidan asks for the site manager’s job; Nora says it’s taken. Aidan walks her to the party, and says goodbye. Nora goes back to check on the sleeping children and finds Aidan still at her house. When she tells him to get out, he hassles her and discovers she hasn’t told Theo about the loan. Aidan blackmails Nora: unless she makes Theo employ him, he will tell Theo of her debt. She brings up an accident that has ruined Aidan’s reputation, but he brushes it off and leaves. Later, Nora suggests that Theo should hire Aidan. Theo says Aidan caused the accident and can’t be trusted. Christmas Day. Nora plays with the children. Theo and his wealthy friend Gerry arrive. Gerry enjoys the love and comfort of Nora’s family life. Nora stops Theo from answering his cell phone in family time. She checks the number when Theo and Gerry take the kids out: its Aidan calling. Theo comes back without the children. Nora panics. However, the kids return just as Christine arrives. She talks about seeing the man paralysed in the accident. Nora changes the subject to Christmas rituals, and conducts one for luck, but remains on edge. Later, Christine urges Nora to tell Theo the truth. Christine thinks Gerry has loaned Nora the money, as he clearly fancies Nora. Nora suggests Christine should look for another job as the site manager position isn’t certain. Christine goes to buy cigarettes. Theo takes the kids out. Gerry and Nora discuss the past. Gerry says goodbye; he’s ill, and needs treatment in Mexico. Then he tells Nora he’s in love with her, and asks her to run away with him. She says no. He pushes her for a kiss; she fights him off. He leaves, saying she has been teasing him in the hope of inheriting his money. Christine comes back with Aidan, whom she met at the shops. She goes to find Theo and the kids; Nora tells Aidan he can’t stay, but that he has got the job– and he leaves happy. Later, Nora tells Theo they should go on holiday, to get him out of Aidan’s reach. Theo gets tetchy; Christine feels awkward; Gerry blunders back, drunk. The situation becomes tense. Theo makes Nora show off her ‘party piece’ dance. She does, on the condition that Theo will go away with her the next day. Boxing Day. Christine is minding the kids. Aidan turns up, and Christine discovers he lent Nora the money. Aidan tells Christine what happened in the accident: a worker fell off the roof, and instead of ringing the ambulance, Aidan rang the boss, who told him there was no accident insurance at their site, and to take the worker to Theo’s building site, which was insured. Theo and Nora come home, drunk. Theo tries to throw Aidan out. Aidan thanks him for the job, then sees Theo is confused and tells him about Nora’s loan. The truth comes out: Nora has forged Theo’s name on a bank loan to clear her debt; Theo has turned down a kickback from Aidan for his role in the accident fraud. Christine convinces Aidan to leave, threatening vengence. Theo and Nora face each other over the fallout of their lies and the wreckage of their lives – and Nora has to decide what to do next. 05 ABOUT HENRIK IBSEN Father of realist theatre (and two children) Henrik Johan Ibsen (1828 – 1906) was born and raised in Skein, Norway. His first job was as an apothecary’s apprentice, and at the age of 18, he fathered a son, Hans, after an affair with his employer’s maid. Ibsen wrote his first play, Catiline, at the age of 20. Though rejected by the Christiania Theatre, it was privately published in 1850 under the pseudonym Brynjolf Bjarme. Christiana Theatre accepted his second play, The Burial Mound, which was staged in 1850 under the same pseudonym. Having failed his university entrance exams, Ibsen spent the early 1850s working in the Norwegian Theatre in Bergen and writing plays; some were staged, but none successful. In 1857 he took 06 6 a job at the Christiania Theatre. In 1858, his play The Vikings of Helgeland was rejected by The Royal Theatre, Copenhagen, because of its ‘crudeness’, so Ibsen produced it himself at the Christiania National Theatre later that year. He also married Suzannah Thoresen, and they had a son, Sigurd, in 1859. The 1860s began badly for Ibsen: he was attacked by the theatre’s Board for “lack of enterprise” and in 1862 the theatre company went bankrupt so Ibsen lost his job. However, he continued to write – not just plays, but poems and articles, some of which found willing publishers. In 1863, Ibsen was awarded a grant to study art and literature in Rome, which he took up in 1864 after producing another of his own plays, The Pretenders, in Christiania. The “Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, Ibsen wrote numerous plays, including some of his most famous: The Wild Duck, Ghosts, Hedda Gabler, The Master Builder and Little Eyolf. ” Italian trip inspired a ‘dramatic poem’, Brand, which was published in 1866 and well-received. Ibsen was awarded an annual government grant, allowing him to focus on his writing with greater financial freedom. The next few years were spent travelling (from homes in Italy and Germany) and writing: works from this time include Peer Gynt and The League of Youth. In 1871, Ibsen’s book Poems was successfully published. During the 1870s, his work attracted international attention, and he was awarded honours in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. A Doll’s House was published in 1879, the second of 12 plays that were later grouped as his ‘Realist Cycle’. Its first production was in Copenhagen on 21 December 1879. In 1880, ‘Quicksands’, an adaptation of Pillars of Society, was produced in London – the first presentation of an Ibsen play on the English stage. In 1882, ‘The Child Wife’, an adaptation of A Doll’s House, was performed in Milwaukee – the first presentation of an Ibsen play on the American stage. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, Ibsen wrote numerous plays, including some of his most famous: The Wild Duck, Ghosts, Hedda Gabler, The Master Builder and Little Eyolf. Though many were produced to acclaim, some critics continued to dismiss Ibsen as a dramatist during his lifetime. In 1900, Ibsen suffered a stroke, which ended his writing career. He died six years later, aged 78. 07 7 ABOUT EMILY PERKINS Modern writer (and mother of three) Born in Christchurch, Emily Perkins was raised in Auckland and Wellington. She began her working life as a TV actor in the series OPEN HOUSE, before starting tertiary study at Toi Whaakari: New Zealand Drama School. She later attended Victoria University where she studied creative writing with Bill Manhire. In 1996, her first book — Not Her Real Name and Other Stories — was published by Picador. It was shortlisted for the New Zealand Book Awards, won the Best First Book (Fiction) Award and later won the Faber Award in the UK. Emily Perkins is now best known as a novelist; her books include Leave Before You Go (1998), 08 8 The New Girl (2001 – shortlisted for the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize), and Novel About My Wife (2008 – winner of the Montana Medal for Fiction at the 2009 Montana New Zealand Book Awards). The latter novel was largely written while Emily was the 2006 Buddle Findlay Sargeson Fellow. In 2011, Emily won an Arts Foundation of New Zealand Laureate Award. Her most recent novel, The Forrests, was published in 2012 to critical acclaim. Emily is married, has three children, and lives in Wellington, where she teaches writing at Victoria University’s International Institute of Modern Letters. This adaptation of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House is her first major work for the theatre. 09 9 ABOUT A DOLL Nora and her legacy Nora is one of the most famous female figures in modern drama. George Bernard Shaw famously described Nora’s final exit from A Doll’s House as “the door slam heard ‘round the world”. Here are some critical perspectives on Nora and the ‘feminism’ of A Doll’s House, in its own time and today: "I thank you for your toast but must disclaim the honour of having consciously worked for women's rights. I am not even quite clear what this women’s rights movement really is. To me it has seemed a problem of humanity in general." Henrik Ibsen in a speech to the Norwegian Society for Women's Rights, 1898 “A Doll’s House is a tragedy in which Nora ultimately leaves by a door to a world of new possibilities. Even though the main dramatic conflict between the partners to the marriage remains unresolved, the end of the play sees the tragic element muted.” Bjørn Hemmer in The Cambridge Companion to Ibsen, 2004 10 “The heroine of A Doll House (sic) evolves from a conventional housewife into a social rebel. Her sustaining home is exposed as a spiritual prison.” “… it is hard to ignore the play's strong feminist resonances in a [modern] culture where it is blindingly obvious that any woman who puts herself in the public eye will become a target for abuse… it seems difficult to deny that virulent prejudice against women and the pressure on them to behave in certain ways still exist. Ibsen himself wrote in a note on his work-inprogress that women can't be themselves in an ‘exclusively male society, with laws made by men and with prosecutors and judges who assess feminine conduct from a masculine standpoint’.” Susanna Rustin in The Guardian, 2013 Rick Davis and Brian Johnston in Ibsen in an Hour, 2009 “Obviously in the original play, society is very different, much more overtly patriarchal, and I’m interested in how society has and hasn’t changed. In Ibsen’s version, it’s about somebody for whom change is coming inevitably and inexorably, although she doesn’t know how or where it’s coming from or what form it’s going to take. The questions we’re asking are: can I engender change in my own life, how would I do it and have I got the imagination and courage to do it?” Emily Perkins in a NZ Listener interview, 2015 TALKING POINTS • Ibsen says that his play deals with the matter of “humanity” rather than specifically “women’s rights”. What do you think he means by this? How might this statement apply to A Doll’s House? • How do you think the role of women in society has changed since the turn of the twentieth century? Look for domestic and personal examples, as well as large-scale public and political ones. • Susanna Rustin says that in today’s society “any woman who puts herself in the public eye will become a target for abuse”. If you check today’s news, what evidence is there to support this view? 11 CHANGES AND CHALLENGES A classic adaptation So how does Emily Perkins’ adapted version of A Doll’s House differ from Henrik Ibsen’s original play? A DOLL’S HOUSE – 1879 A DOLL’S HOUSE – 2015 • The play is set at Christmas in Scandinavia — in the northern hemisphere’s winter • The play is set at Christmas in New Zealand — in the southern hemisphere’s summer • Nora lives in a comfortable suburban house with her husband and three children • Nora lives in an eco-house on a life‑style block with her husband and two children • Nora’s husband Torvald is a bank lawyer • Nora’s husband Theo is a builder • Torvald gets a promotion and a raise in salary, which will come into effect in January • Nora’s friend Kristine, a widow and office worker, asks Nora to ask Theo to make her his clerk now he is bank manager – and he agrees • Nora has borrowed money from Torvald’s clerk and old school mate (Krogstad) to take Torvald on a holiday after Torvald has a breakdown • Krogstad has a reputation for being dishonest, having “done 12 • Theo gets a big building contract for a new subdivision, contract coming in January • Nora’s friend Christine, a divorcee and failed business woman, asks Nora to ask Theo to give her a job as site-manager – and he agrees • Nora has borrowed money from Theo’s old school friend and contractor (Aidan) to save Theo’s business and renovate the family home • Aiden has a reputation for being dishonest, because 4 years ago at a building site accident something rash” and then taken to crime to protect himself from consequences • Nora claims she has got the money as an inheritance from her father • Nora has forged her father’s signature on the loan guarantee, but accidentally dates the signature after her father’s death • Krogstad blackmails Nora to get Torvald to let him keep his job instead of giving it to Kristine • Nora wants to ask Dr. Rank to lend her money, but backs out when he declares his love for her where someone was gravely injured, he took orders from his and Theo's boss in a cover up relating to insurance. • Nora claims she has got the money from a trust fund set up by her grandmother • Nora has forged Theo’s signature on the bank loan application she is taking out to clear her debt to Aidan • Aidan blackmails Nora to get Theo to give him, rather than Christine, the sitemanager’s job • Nora denies Gerry’s accusation that she flirts with him because he’s rich, and pushes him off 13 • Kristine, who once had a relationship with Krogstad, pleads for him to release Nora from the blackmail threat, but he refuses • Christine, who was friends with Aidan at school, discovers Aidan lent Nora the money and begs him to leave Theo and Nora alone • The truth comes out: Torvald is worried he will be implicated in Nora’s fraud and is furious with Nora for making a deal with Krogstad • The truth comes out: Theo is implicated in the accident scam and is furious with Nora for her dealings with Aidan behind his back • Nora realises that her husband will not take any measures to save her reputation, and that her marriage is based on false expectations • Nora realises that her husband will not take any measures to save her reputation, and that her marriage is based on false expectations • Nora leaves her husband and children to go into the world, ‘grow up’ and become a woman in her own right, not a man’s plaything • Nora leaves her husband and children to go into the world, ‘grow up’ and become a woman in her own right, not just a social ‘mask’ TALKING POINTS • Look at this chart of changes between the original and the adapted versions of the play. Which do you think are the most significant? What do the changes say about how social aspirations have altered? • Choose one character from the play, and write a ‘compare and contrast’ piece detailing the characteristics and traits that are similar and different in that character in the two versions of the play. • The adapted play maintains the original play’s classic three-act structure, with the acts taking place on Christmas Eve, Christmas Day and Boxing Day. What is the ‘climax point’ of each act? • Read p 17 of the ATC production script. How does the language inform you of the period and setting of this version? Identify the specific words and phrases that locate this version in place and time. 14 15 Colin McColl NEW DIRECTIONS Bringing Ibsen to modern New Zealand This production of A Doll’s House (in a version by New Zealand author Emily Perkins) will be the first Henrik Ibsen play to be presented by Auckland Theatre Company. The company’s Artistic Director, Colin McColl, believes that Ibsen “has been much neglected by New Zealand theatre,” but that the playwright’s work has plenty to offer contemporary audiences. Here, Colin discusses the importance of Ibsen, and his own approach to A Doll’s House as the production’s director. “Ibsen is the father of modern theatre. What was so revolutionary about Ibsen (and Chekhov) in their time was that suddenly people were hearing and seeing people on 16 stage that looked and sounded just like them. Before that, there was kind of heightened way of acting on stage, and a heightened way of speaking on stage. But with Ibsen and Chekhov it was like it was real. There was no barrier between what the audience was seeing on stage and the way they lived their lives. Maybe they didn’t have lives quite like some of the characters, but it wasn’t artificial. “I think the English theatre has a lot to answer for in the way that they’ve kept Ibsen corralled in a nineteenth-century, old-fashioned idiom: no European production of Ibsen today is ever presented in nineteenth-century clothes. It’s always presented absolutely contemporarily, because they’re honouring Ibsen’s intention that “I’m a huge fan of Ibsen – he asked so many great questions about life and how we live, and A Doll’s House is particularly striking in that way… for me it’s a fascinating story about values and the pressure we put on ourselves and what happens when change is not only necessary but imaginable.” Emily Perkins in an interview in the NZ Listener, April 2015 the people on stage should be recognisable and real to the people in the audience. The language is changed to contemporary language – even in Norway, the plays are done in contemporary Norwegian, not the Norwegian of Ibsen’s day. We tend to get these rather stilted translations that have been done for productions with a Victorian setting. But that’s not honouring Ibsen’s intention. “A Doll’s House is the most performed of Ibsen’s plays. He called it ‘a play of modern life’ when he was writing to a friend about it while he was working on the production. “It’s hard for us today to understand and appreciate the sensation that the play caused when it was first done. In nineteenth-century Europe, the idea of a woman forsaking her marriage and her unquestioning obedience to her husband, and leaving her family, was pretty darn shocking. But if you think about it, how many women today leave their husbands and children in one sweep? They would probably come to some sort of arrangement about the children: to just up and leave your husband AND children is still pretty unusual. “Classic plays are usually classics because they have very solid dramaturgy: the story-telling is really good. Great characters and psychological truths mean that we can respond to these plays even a couple of centuries after they were written. “About 25 years ago, when I was 17 at the first Ibsen festival in Norway, it was fascinating to see all the different interpretations of Ibsen’s plays, and the way that European directors were interested not so much in the drawing-room settings (because if you read the scripts of these Ibsen plays, they’re all set in a ‘living-room’ environment), but in playing around with the form. What the actors were doing and saying was completely real and naturalistic, but the settings were abstract. And that style has increased and increased. The most recent example is from Simon Stone – an Australian director – who did a fabulous Australian version of Ibsen’s Wild Duck. He cut the play down from 13 actors to just five, and really streamlined the script, getting it back to the basic storyline… It was fantastically successful; it played all over the world, including in Norway. “The other thing I think is really important about Ibsen’s work is that underneath this ‘drawing-room’ exterior the work seethes with Norse wildness and witchery. That’s really hard for us to understand in translation. Here in New Zealand, maybe those kind of connections only show in Maori work, where the story is linked to Maori mythology. All of Ibsen’s work is linked to the earth and Norse mythology. Even the names of the characters mean something in Norwegian, and Norwegian audiences understand the links to mythological archetypes. That’s 18 impossible to get in translation. “That’s why I was interested in commissioning a writer to come up with a contemporary and unapologetically Kiwi response to Ibsen’s A Doll’s House. Emily [Perkins] seemed the perfect person for the job. She is not a playwright, but like Ibsen she started in the theatre, as a theatre-maker. Her books – Not Her Real Name and Novel About My Wife – show she’s very interested in the psychology of relationships between husbands and wives. She knows about the joys and irritations of modern relationships… She’s come up with some terrific stuff, particularly for the male characters. I expected her to be able to handle the female characters, but her male characters are fabulous; they’re quite difficult to make work today as they were presented in the original text, but Emily’s managed make them recognisable and contemporary whilst honouring Ibsen. “Emily hasn’t slavishly followed Ibsen’s plot, but she’s been serious and scrupulous about the spirit and the intent of this work.” TALKING POINTS • In an interview with the NZ Listener, Emily Perkins says of her version, “I’m not sure whether to call in an updating, an adaptation or a reframing.” Which term do you think is most appropriate? Why? • Colin indicates that the character’s names were originally intended to suggest links to Norse mythology. Find out the meanings of Nora, Torvald Helmer, Kristine, etc, and research their mythological connections. How does this knowledge affect your perception of each character? • Now look at the names Emily Perkins has chosen for her version. (Torvald becomes Theo, for example.) What do these names mean, or what might they suggest, within a New Zealand context? • One reason the play’s ending was so shocking to its original audiences was that Nora’s departure is not resolved – the playwright does not show whether her extreme behaviour is punished or rewarded, or whether she returns to her family. This was so unusual for plays in Ibsen’s era that early audiences didn’t realise the play was over: instead of clapping, they waited in silence for the explanatory final scene! How to you respond to this lack of resolution in the play? If you had to write an additional final scene to follow Nora’s departure, what would happen in it? 19 Tony Rabbit SET AND LIGHTING DESIGN Robert Therrien's No Title (Table and Four Chairs) 2003, which was part of the ARTIST ROOMS collection at Tate Modern. Picture courtesy Tate. As both Set and Lighting Designer, Tony Rabbit is responsible for creating the visual world of A Doll’s House. He explains his production concepts – from panda pits to pipelines. “The main thing is that the space in which the play takes place is not realistic in any sense at all. It’s a psychic space, slanted to Nora’s point of view. “There’s no furniture. There’s only a soft pit construction, with a whole lot of soft toys in it. It’s an uncomfortable place to perform, but it allows possibilities that you wouldn’t necessarily get in a more standard sort of set. It forces Colin 20 and the actors to find new ways to do stuff. “One image in my mind when I started this process came from a poem by Fleur Adcock. She describes this woman in this ordinary house, but underneath this house is a huge chasm with a river flowing through it. I thought that was such a great image: you’re in this domestic situation, everything seems nice and cosy, you’re doing all the right things, everything’s ticking over – but just underneath the floorboards is this huge dark river. Two of the key things in developing this design were repetition and scale. One of the depth-charges that started this process is a photograph I took in the Tate Gallery in London; it’s an installation by Robert Therrien, and it’s this huge table and chairs. Therrien has gone on and done a whole series of things like this; they’re just extraordinary. For a while I got quite excited about actually doing this in the theatre… you know, taking furniture and scaling it right up. We moved beyond that idea, but it is interesting. It’s a great image. “Another interesting thing I came across is by a Dutch artist, Florentijn Hofman, who put this huge inflatable duck in the harbour in Hong Kong. You look at that thing, and it just messes with your head. It’s witty, but it’s disturbing. “Also there’s this idea of repetition. If you have an ordinary trivial object you can give it ultrasignificance by multiplying it over and over and over again. It can be anything – let’s take a biscuit… One biscuit sitting on a plate is nothing. Ten biscuits lined up, yeah, whatever. A hundred biscuits is quite good, but six thousand of those biscuits all lined up is something completely different. “Now to the set itself… We had the idea of this pit, and having something in it which repeats over and over. We decided we’d do 21 “Ibsen created a ‘poetry of the theatre’ for those modern plays. The stage space does not create just a plausible ‘setting’ or milieu; it is a potent source of metaphors that are integral and active elements of the plot.” Rick Davis and Brian Johnston Ibsen in an Hour that with a soft toy. More soft toys are better. And many more soft toys are better again. And 1,500 soft toys are really, really good! So our central ‘pit’ is full of soft toy pandas. They’ve come from China, and they’re a little bunch of sweeties. “Also on stage is a large dead tree. It will be a real tree, like a pine tree. You see them all over the place, where they’ve been blown over by the wind. Their roots come right up and they’ve got big broken branches that stick out. The idea is to get one of those and waterblast the dirt off it, so 22 it’s this great big sculpture lying on its side that is an incredibly organic thing, as opposed to these pandas arranged in this pit, which is very structured and not organic at all. The pandas are industrial and deliberate, whereas the tree is wild, and rough, and a completely different thing. “In the script, there’s talk about how they’re living on land that has been pushed up and carved over, and there’s rubble and rubbish around the place. Realistically, if you like, the tree stands for that – but it’s much more than that. It’s to do with the outside world: the things that you’re afraid of in your life; the things that go bump in the night. “The other thing on stage is a big thick water pipe. In the script, the water becomes a big deal. The pipe on stage is much bigger than an ordinary water pipe – we’re going to take it right up to the roof. Realistically, it would just be a tap, but here it’s a much bigger than normal, because it’s from Nora’s point of view, and it’s a big deal to her. “The other thing we’ve done with the stage is to take the first two rows of seats out of the auditorium, and hang the set 1.8m over the edge of the stage floor. It’s thrust into the audience. It brings this quite intimate piece right into the room with the audience. “The colour of the set is just a neutral grey, so with the black and white pandas the whole thing is very monochromatic. The actors provide the interest. One of the reasons we chose pandas is that the black and white provides a really good contrast against skin. When I light this, I’ve got a completely neutral space to light, so that the actors will really ‘pop’ against the background.” 23 LIGHTING ATC Production Manager Andrew Malmo describes how Lighting Designer Tony Rabbit will light A Doll's House using only four main theatre lights. "Three of these lights are very sophisticated intelligent lights with the ability to change the shape, colour and beam-angle of the light. This gives Tony the ability to change the mood of the scene through colour changes, and to choose where the audience should look by changing the shape of the light and isolating the subject. At times he may make the stage look quite pretty, or he may also flood the stage in coloured (or white) light, opening the space out and exposing the brutal reality of the stage set (and the characters’ predicament). The fourth light is used at the end, but to avoid a spoiler you’ll need to see the show to know what that light is used for. There may be some other incidental lights added in for highlighting a specific area or piece of scenery, however at the time of writing these have not been decided on." TALKING POINTS • In Ibsen’s original play, Nora says to Torvald that she feels she has spent her life “in a play-pen”. How does this set, and the way the actors make use of it, highlight or reinforce this idea? • Key ideas in this production design are repetition and scale. Create your own design for Nora’s home, using one of these ideas in a completely different way from Tony Rabbit’s design. • How does the lighting change the location / mood / time during the performance? Identify a particular scene where the lighting played a strong role, and explain what techniques were used and their effect. • Make a case for or against the use of the soft-toy pandas in this production. 24 25 Nic Smillie COSTUME DESIGN Dressing the dolls Costume designer Nic Smillie says that with her design she wants “to honour the Nordic roots of this play, and incorporate ideas Ibsen would want to incorporate”, even within the revised context of a modern New Zealand summer holiday. “We are taking a rather 'organic' approach to the costumes. That often happens with new work… it’s about seeing what unfolds during the rehearsal process. “Colin and I have been making design decisions based on what the actors are discovering about their characters, taking into account everyone's response to the set and their interpretations of the script. “Our current take is that the 26 characters are costumed in the way that Nora sees or remembers them, as a sort of stylised summary of each person. The set is abstract and has been designed to represent her version of her world; therefore it seems obvious that the costumes would be that way too. “This means that although we still want to portray all the things that are mentioned in the script (such as that it is summer and Christmastime in New Zealand) the costumes are not really a marker of time, but a symbol of each character. “We plan to dress children in clothes that kids are often keen to stay in (their favourite outfit perhaps, or pyjama bottoms) but that do not necessarily fit with it being day or night, bedtime or not. “Theo is relatively simply attired but his clothes have quality and integrity. His shirt is soft and feels nice; he wears things that have a good aesthetic but are not necessarily brand new..... “Gerry is a bit more flashy, showing his wealth and position. Aidan is simply dressed; he is neither super-stylish nor roughlooking, allowing for his different character traits to come through. “Christine is stylish. She's an interior designer, and even though she has fallen on hard times, she still looks great. Nora herself is well-presented and dressed in a 1950s-style dress. It could be vintage, or something she has made for herself from an old pattern. Whatever it is, it is about her making the best from something that did not cost her much. “In the design for this show, I have also severely limited the colour palette. Everything is the same world or language as the set: black, white and grey, with just small spots of colour. Basically I have reflected the world of the set back onto the characters.” TALKING POINTS • Which aspects of the costumes most effectively connect the characters to New Zealand summer AND to the symbolic world of the ‘doll’s house’ from Nora’s point of view? • The characters in this production wear the same costumes throughout. What might be some of the practical and conceptual reasons for this choice? • How do the ‘spots of colour’ Nic mentions work to emphasise particular aspects of each character? When are they brought into play, and to what effect? 27 RESOURCES AND READINGS ls, Hilton. “The Marrying Kind – A new production of A Doll’s House”. The New Yorker Online. http://www.newyorker.com/ magazine/2014/03/10/the-marrying-kind Published 10-03-2014. Accessed 10-04-2015. Web. Davis, Rick and Brian Johnston. Ibsen in an Hour. Smith and Kraus: Hanover, 2009. Print. Ferguson, Robert. Henrik Ibsen: A New Biography. Richard Cohen Books: London, 1996. Print. ATC EDUCATION ATC Education promotes and encourages teaching and participation in theatre and acts as a resource for secondary and tertiary educators. It is a comprehensive and innovative education programme designed to nurture young theatre practitioners and future audiences. ATC Education has direct contact with secondary school students throughout the greater Auckland region with a focus on delivering an exciting and popular programme that supports the Arts education of Auckland students and which focuses on curriculum development, literacy and the Arts. Auckland Theatre Company acknowledges that the experiences enjoyed by the youth of today are reflected in the vibrancy of theatre in the future. Hopkins, Hagen. “House Work”. NZ Listener. April 18-24 2015. Bauer Media Group: Auckland, 2015. Print. Ibsen, Henrik. (Trans: Rolf Fjelde). Ibsen: Four Major Plays Volume I. Signet Classics: New York, 2006. CURRICULUM LINKS McFarlane, James (Ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Ibsen. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2004. Print. Reis Mayer, Laura. “A Teacher’s Guide to the Signet Classics Edition of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House.” Penguin Group. http://www.penguin. com/static/pdf/teachersguides/DollshouseTG.pdf Published 2008. Accessed 02-03-2015. Web. Rustin, Susanna. “Why A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen is more relevant than ever.” The Guardian Online. http://www.theguardian.com/ stage/2013/aug/10/dolls-house-henrik-ibsen-relevant Published 10-082013. Accessed 02-03-2015. Web. 28 ATC Education activities relate directly to the PK, UC and CI strands of the NZ Curriculum from levels 5 to 8. They also have direct relevance to many of the NCEA achievement standards at all three levels. All secondary school Drama students (Years 9 to 13) should be experiencing live theatre as a part of their course work, Understanding the Arts in Context. Curriculum levels 6, 7 and 8 (equivalent to years 11, 12 and 13) require the inclusion of New Zealand drama in their course of work. The NCEA external examinations at each level (Level 1 – AS90011, Level 2 – AS91219, Level 3 – AS91518) require students to write about live theatre they have seen. Students who are able to experience fully produced, professional theatre are generally advantaged in answering these questions. 29 ENGAGE JOIN THE CONVERSATION Post your own reviews and comments, check out photos of all our productions, watch exclusive interviews with actors and directors, read about what inspires the playwrights we work with and download the programme and education packs. Places to find out more about ATC and engage with us: www.atc.co.nz facebook.com/TheATC @akldtheatreco AUCKLAND THEATRE COMPANY 487 Dominion Road, Mt Eden PO Box 96002, Balmoral, Auckland 1342 Ph: 09 309 0390 Fax: 09 309 0391 Email: atc@atc.co.nz 30