Pursuing American Ideals | Sample Chapter

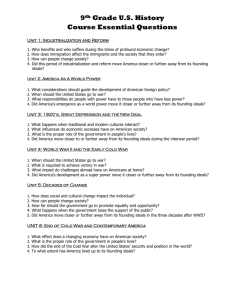

advertisement

Sample Lesson Sample Lesson Welcome to History Alive! Pursuing American Ideals. This document contains everything you need to teach the sample lesson “Defining and Debating America’s Founding Ideals.” We invite you to use this sample lesson today to discover how the TCI Approach can make history come alive for your students. Contents Overview: Sample Lesson 2: Defining and Debating America’s Founding Ideals 2 Student Text 5 Procedures12 Notebook Guide 17 Guide to Reading Notes 19 Assessment21 Differentiating Instruction 22 Enhancing Learning 24 1. Watch a lesson demonstration 2. Learn about strategies behind the program 3. Discover the new and improved Teacher Subscription and Student Subscription 1 info@teachtci.com | 800-497-6138 www.teachtci.com www.teachtci.com/historyalive-pai Establishing an American Republic 1492–1896 Expanding American Global Influence 1796–1921 1 What Is History? 19 Foreign Policy: Setting a Course of Expansionism 2 Defining and Debating America’s Founding Ideals 3 Setting the Geographic Stage 4 The Colonial Roots of America’s Founding Ideals 5 Americans Revolt History Alive! Pursuing American Ideals centers on the five founding ideals from the Declaration of Independence: equality, rights, liberty, opportunity, and democracy. Each generation has struggled with these ideals. Some have made little progress toward achieving them. Others have made great progress. This program invites students to become engaged in this struggle, from establishing an American republic to the making of modern America. Sample Lesson: 2 Defining and Debating America’s Founding Ideals 6 Creating the Constitution 7 An Enduring Plan of Government 8 Changes in a Young Nation 21 Acquiring and Managing Global Power 22 From Neutrality to War 23 The Course and Conduct of World War I 24 The Home Front 25 The Treaty of Versailles: To Ratify or Reject? 9 A Dividing Nation 10 The Civil War 11 Reconstruction The Roaring Twenties and the Great Depression 1914–1944 26 Understanding Postwar Tensions Industrialism and Reform 1840–1920 12 Change and Conflict in the American West 13The Age of Innovation and Industry 14Labor’s Response to Industrialism 15 Through Ellis Island and Angel Island: The Immigrant Experience 16 Uncovering Problems at the Turn of the Century 17 The Progressives Respond 18 Progressivism on the National Stage 2 20 The Spanish-American War 27 The Politics of Normalcy 28 Popular Culture in the Roaring Twenties 29 The Clash Between Traditionalism and Modernism 30 The Causes of the Great Depression 31 The Response to the Economic Collapse 32 The Human Impact of the Great Depression 33 The New Deal and Its Legacy Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Overview World War II and the Cold War 1917–1960 34 Origins of World War II 35 The Impact of World War II on Americans 36 Fighting World War II Tumultuous Times 1954–1980 47 The Age of Camelot The Making of Modern America 1980–Present 48 The Great Society 55 A Shift to the Right Under Reagan 49 The Emergence of a Counterculture 56 Ending the Cold War 37 The Aftermath of World War II 50 The United States Gets Involved in Vietnam 38 Origins of the Cold War 51 Facing Frustration in Vietnam 39 The Cold War Expands 52 Getting Out of Vietnam 40 Fighting the Cold War at Home 53 The Rise and Fall of Richard Nixon The Search for a Better Life 1945–1990 54 Politics and Society in the “Me” Decade 57 U.S. Domestic Politics at the Turn of the 21st Century 58 U.S. Foreign Policy in a Global Age 59 9/11 and Its Aftermath: Debating America’s Founding Ideals 41 Peace, Prosperity, and Progress 42 Two Americas 43 Segregation in the Post–World War II Period 44 The Civil Rights Revolution: “Like a Mighty Stream” 45 Redefining Equality: From Black Power to Affirmative Action 46 The Widening Struggle F R E E 3 0 DAY T R I A L Test-drive with a 30 Day Trial With the Teacher Subscription, teachers can get an entire class interacting with one computer, an internet connection and a projector. Students thrive on the immediate feedback they get using the Student Subscription’s Reading Challenges. www.teachtci.com/trial 3 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Overview (continued) Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning USHS_SE_02.qxp:USHS_SE_TemplateReference 3/8/07 3:41 PM Page 15 Defining and Debating America’s Founding Ideals What are America’s founding ideals, and why are they important? 2.1 Introduction We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. —Thomas Jefferson, Declaration of Independence, 1776 In these two sentences, Jefferson set forth a vision of a new nation based on ideals. An ideal is a principle or standard of perfection that we are always trying to achieve. In the years leading up to the Declaration, the ideals that Jefferson mentioned had been written about and discussed by many colonists. Since that time, Americans have sometimes fought for and sometimes ignored these ideals. Yet, throughout the years, Jefferson’s words have continued to provide a vision of what it means to be an American. In this chapter, you will read about our nation’s founding ideals, how they were defined in 1776, and how they are still being debated today. 5 An early edited draft of the Declaration of Independence The Granger Collection, New York On a June day in 1776, Thomas Jefferson set to work in a rented room in Philadelphia. His task was to draft a document that would explain to the world why Great Britain’s 13 American colonies were declaring themselves to be “free and independent states.” The Second Continental Congress had appointed a five-man committee to draft this declaration of independence. At 33, Jefferson was one of the committee’s youngest and least experienced members, but his training in law and political philosophy had prepared him for the task. He picked up his pen and began to write words that would change the world. Had he been working at home, Jefferson might have turned to his large library for inspiration. Instead, he relied on what was in his head to make the declaration “an expression of the American mind.” He began, In many ways Thomas Jefferson, shown here with his fellow committee members Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, was an odd choice to write the Declaration of Independence. Not only was Jefferson young and inexperienced, he was also a slaveholder. For all his fine words about liberty and equality, Jefferson proved unwilling to apply his “self-evident” truths to the men and women he held in bondage. 15 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Chapter 2 3/8/07 3:34 PM Page 16 2.2 The First Founding Ideal: Equality “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” When Jefferson wrote these words, this “truth” was anything but self-evident, or obvious. Throughout history, almost all societies had been divided into unequal groups, castes, or social classes. Depending on the place and time, the divisions were described in different terms—patricians and plebeians, lords and serfs, nobles and commoners, masters and slaves. But wherever one looked, some people had far more wealth and power than others. Equality, or the ideal situation in which all people are treated the same way and valued equally, was the exception, not the rule. Defining Equality in 1776 For many Americans of Jefferson’s time, the ideal of equality was based on the Christian belief that all people are equal in God’s eyes. The colonists saw themselves as rooting this ideal on American soil. They shunned Europe’s social system, with its many ranks of nobility, and prided themselves on having “no rank above that of freeman.” This view of equality, however, ignored the ranks below “freeman.” In 1776, there was no equality for the half million slaves who labored in the colonies. Nor was there equality for women, who were viewed as inferior to men in terms of their ability to participate in society. In 1848, a group of women used the Declaration of Independence as a model for their own Declaration of Sentiments on women’s rights. They declared that “all men and women are created equal.” Achieving equality, however, has been a tremendous struggle. This photograph shows a woman, some 70 years later, still marching for the right to vote. For much of our history, African Americans were treated as less than equal to whites. No one knew that better than these Memphis sanitation workers when they went on strike in 1968. Their signs reminded the nation that each person in our society should be treated with equal respect. 16 Chapter 2 6 Debating Equality Today Over time, Americans have made great progress in expanding equality. Slavery was abolished in 1865. In 1920, a constitutional amendment guaranteed all American women the right to vote. Many laws today ensure equal treatment of all citizens, regardless of age, gender, physical ability, national background, and race. Yet some people—both past and present—have argued that achieving equal rights does not necessarily mean achieving equality. Americans will not achieve equality, they argue, until we address differences in wealth, education, and power. This “equality of condition” extends to all aspects of life, including living standards, job opportunities, and medical care. Is equality of condition an achievable goal? If so, how might it best be achieved? These and other questions about equality are likely to be hotly debated for years to come. Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning USHS_SE_02.qxp:USHS_SE_TemplateReference USHS_SE_02.qxp:USHS_SE_TemplateReference 11/5/07 4:22 PM Page 17 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning 2.3 The Second Founding Ideal: Rights “They are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.” The idea that people have certain rights would have seemed self-evident to most Americans in Jefferson’s day. Rights are powers or privileges granted to people either by an agreement among themselves or by law. Living in British colonies, Americans believed they were entitled to the “rights of Englishmen.” These rights, such as the right to a trial by jury or to be taxed only with their consent, had been established slowly over hundreds of years. The colonists believed, with some justice, that having these rights set them apart from other peoples in the world. Defining Rights in 1776 Jefferson, however, was not thinking about specific legal or political rights when he wrote of “unalienable rights.” He had in mind rights so basic and so essential to being human that no government should take them away. Such rights were not, in his view, limited to the privileges won by the English people. They were rights belonging to all humankind. This universal definition of rights was strongly influenced by the English philosopher John Locke. Writing a century earlier, Locke had argued that all people earned certain natural rights simply by being born. Locke identified these natural rights as the rights to life, liberty, and property. Locke further argued that the main purpose of governments was to preserve these rights. When a government failed in this duty, citizens had the right to overthrow it. Debating Rights Today The debate over what rights our government should preserve began more than two centuries ago, with the writing of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights, and continues to this day. The Constitution (and its amendments) specifies many basic rights, including the right to vote, to speak freely, to choose one’s faith, and to receive fair treatment and equal justice under the law. However, some people argue that the government should also protect certain economic and social rights, such as the right to health care or to a clean environment. Should our definition of rights be expanded to include new privileges? Or are there limits to the number of rights a government can protect? Either way, who should decide which rights are right for today? This celebration of the Bill of Rights was painted by Polish American artist Arthur Szyk in 1949. It includes a number of Revolutionary War–era symbols, such as flags, Minutemen, and America’s national bird, the bald eagle. Szyk wanted his work to promote human rights. “Art is not my aim,” he maintained, “it is my means.” Defining and Debating America’s Founding Ideals 7 17 USHS_SE_02.qxp:USHS_SE_TemplateReference 3/8/07 3:59 PM Page 18 “That among these [rights] are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” By the time Jefferson was writing the Declaration, the colonists had been at war with Britain for more than a year—a war waged in the name of liberty, or freedom. Every colony had its liberty trees, its liberty poles, and its Sons and Daughters of Liberty (groups organizing against the British). Flags proclaimed “Liberty or Death.” A recently arrived British immigrant to Maryland said of the colonists, “They are all liberty mad.” Defining Liberty in 1776 Liberty meant different things to different colonists. For many, liberty meant political freedom, or the right to take part in public affairs. It also meant civil liberty, or protection from the power of government to interfere in one’s life. Other colonists saw liberty as moral and religious freedom. Liberty was all of this and more. However colonists defined liberty, most agreed on one point: the opposite of liberty was slavery. “Liberty or slavery is now the question,” declared a colonist, arguing for independence in 1776. Such talk raised a troubling question. If so many Americans were so mad about liberty, what should this mean for the one fifth of the colonial population who labored as slaves? On the thorny issue of slavery in a land of liberty, there was no consensus. Every year, millions visit the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia’s Independence National Historic Park. The huge bell was commissioned by the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1753. Its every peal was meant to proclaim “liberty throughout all the land.” Badly cracked and battered, the bell is now silent. But it remains a beloved symbol of freedom. 18 Chapter 2 8 Debating Liberty Today If asked to define liberty today, most Americans would probably say it is the freedom to make choices about who we are, what we believe, and how we live. They would probably also agree that liberty is not absolute. For people to have complete freedom, there must be no restrictions on how they think, speak, or act. They must be aware of what their choices are and have the power to decide among those choices. In all societies, there are limits to liberty. We are not, for example, free to ignore laws or to recklessly endanger others. Just how liberty should be limited is a matter of debate. For example, most of us support freedom of speech, especially when it applies to speech we agree with. But what about speech that we don’t agree with or that hurts others, such as hate speech? Should people be at liberty to say anything they please, no matter how hurtful it is to others? Or should liberty be limited at times to serve a greater good? If so, who should decide how, why, and under what circumstances liberty should be limited? Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning 2.4 The Third Founding Ideal: Liberty USHS_SE_02.qxp:USHS_SE_TemplateReference 3/8/07 4:00 PM Page 19 “That among these [rights] are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Something curious happened to John Locke’s definition of natural rights in Jefferson’s hands. Locke had included property as the third and last right in his list. But Jefferson changed property to “the pursuit of Happiness.” The noted American historian Page Smith wrote of this decision, The change was significant and very American . . . The kings and potentates, the powers and principalities of this world [would not] have thought of including “happiness” among the rights of a people . . . except for a select and fortunate few. The great mass of people were doomed to labor by the sweat of their brows, tirelessly and ceaselessly, simply in order to survive . . . It was an inspiration on Jefferson’s part to replace [property] with “pursuit of happiness” . . . It embedded in the opening sentences of the declaration that comparatively new . . . idea that a life of weary toil . . . was not the only possible destiny of “the people.” —Page Smith, A New Age Now Begins, 1976 The Granger Collection, New York Horatio Alger, author of Strive and Succeed, wrote more than 100 “dime novels” in the late 1800s. Many of these inexpensive books were about opportunity. They showed how a poor boy might achieve the American dream of success through hard work, courage, and concern for others. The destiny that Jefferson imagined was one of endless opportunity, or the chance for people to pursue their hopes and dreams. Defining Opportunity in 1776 The idea that America was a land of opportunity was as old as the colonies themselves. Very soon after colonist John Smith first set foot in Jamestown in 1607, he proclaimed that here “every man may be master and owner of his owne labour and land.” Though Jamestown did not live up to that promise, opportunity was the great lure that drew colonists across the Atlantic to pursue new lives in a new land. Debating Opportunity Today More than two centuries after the Declaration of Independence was penned, the ideal of opportunity still draws newcomers to our shores. For most, economic opportunity is the big draw. Here they hope to find work at a decent wage. For others, opportunity means the chance to reunite families, get an education, or live in peace. For all Americans, the ideal of opportunity raises important questions. Has the United States offered equal opportunity to all of its people? Or have some enjoyed more opportunity to pursue their dreams than have others? Is it enough to “level the playing field” so that everyone has the same chance to succeed in life? Or should special efforts be made to expand opportunities for the least fortunate among us? Defining and Debating America’s Founding Ideals 9 19 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning 2.5 The Fourth Founding Ideal: Opportunity USHS_SE_02.qxp:USHS_SE_TemplateReference 3/8/07 4:01 PM Page 20 “That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” In these few words, Jefferson described the basis of a democracy—a system of government founded on the simple principle that the power to rule comes from the consent of the governed. Power is not inherited by family members, as in a monarchy. Nor is it seized and exercised by force, as in a dictatorship. In a democracy, the people have the power to choose their leaders and shape the laws that govern them. Defining Democracy in 1776 The colonists were familiar with the workings The right to vote is so basic to a democracy that most Americans today think little about it. For much of our history, however, that right was denied to women and most African Americans. Their “consent” was not considered important to those who governed. of democracy. For many generations, the people had run their local governments. In town meetings or colonial assemblies, colonists had learned to work together to solve common problems. They knew democracy worked on a small scale. But two questions remained. First, could democracy be made to work in a country spread over more than a thousand miles? In 1776, many people were not sure that it could. The second question was this: Who should speak for “the governed”? In colonial times, only white, adult, property-owning men were allowed to vote or hold office. This narrow definition of voters did not sit well with many Americans, even then. “How can a Man be said to [be] free and independent,” protested citizens of Massachusetts in 1778, “when he has not a voice allowed him” to vote? As for women, their voices were not yet heard at all. Debating Democracy Today The debate over who should speak for the governed was long and heated. It took women more than a century of tenacious struggle to gain voting rights. For many minority groups, democracy was denied for even longer. Today, the right to vote is universal for all American citizens over the age of 18. Having gained the right to vote, however, many people today do not use it. Their lack of participation raises challenging questions. Why do so many Americans choose not to make their voices heard? Can democracy survive if large numbers of citizens decide not to participate in public affairs? The stars on the official American flag symbolize the 50 states that make up our country. The faces on this painting symbolize the many peoples who have come together to create a democratic society in the United States. 20 Chapter 2 10 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning 2.6 The Fifth Founding Ideal: Democracy USHS_SE_02.qxp:USHS_SE_TemplateReference 3/8/07 4:01 PM Page 21 “Ideals are like stars,” observed Carl Schurz, a German American politician in the late 1800s. “You will not succeed in touching them with your hands, but like the seafaring man on the ocean desert of waters, you choose them as your guides, and, following them, you reach your destiny.” In this book, the ideals found in the Declaration of Independence will serve as your guiding stars. You will come upon these ideals again and again—sometimes as points of pride, sometimes as prods to progress, and sometimes as sources of sorrow. Living up to these ideals has never been a simple thing. Ideals represent the very highest standards, and human beings are far too complex to achieve such perfection. No one illustrates that complexity more clearly than Jefferson. Although Jefferson believed passionately in the Declaration’s ideals, he was a slaveholder. Equality and liberty stopped at the borders of his Virginia plantation. Jefferson’s pursuit of happiness depended on depriving the people who labored for him as slaves the right to pursue happiness of their own. Soon after the Continental Congress approved the Declaration of Independence, it appointed a committee to design an official seal for the United States. The final design appears on the back of the one-dollar bill. One side shows an American eagle holding symbols of peace and war, with the eagle facing toward peace. The other shows an unfinished pyramid, symbolizing strength and endurance. Perhaps another reason for the unfinished pyramid was to show that a nation built on ideals is a work in progress. As long as our founding ideals endure, the United States will always be striving to meet them. The front of the Great Seal features a bald eagle and a shield with 13 red and white stripes, representing the original 13 states. The scroll in the eagle’s beak contains our national motto, E Pluribus Unum, which means “Out of Many, One.” The motto refers to the creation of one nation out of 13 states. Summary Throughout their history, Americans have been inspired and guided by the ideals in the Declaration of Independence—equality, rights, liberty, opportunity, and democracy. Each generation has struggled with these ideals. The story of their struggles lies at the heart of our nation’s history and who we are as Americans. Equality The Declaration of Independence asserts that “all men are created equal.” During the past two centuries, our definition of equality has broadened to include women and minority groups. But we are still debating the role of government in promoting equality today. Rights The Declaration states that we are all born with “certain unalienable Rights.” Just what these rights should be has been the subject of never-ending debates. Liberty One of the rights mentioned in the Declaration is liberty—the right to speak, act, think, and live freely. However, liberty is never absolute or unlimited. Defining the proper limits to liberty is an unending challenge to a free people. Opportunity This ideal lies at the heart of the “American dream.” It also raises difficult questions about what government should do to promote equal opportunities for all Americans. Democracy The Declaration of Independence states that governments are created by people in order to “secure these rights.” Governments receive their “just powers” to rule from the “consent of the governed.” Today we define such governments as democracies. Defining and Debating America’s Founding Ideals 11 21 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning 2.7 In Pursuit of America’s Ideals Overview and Objectives Suggested time: This lesson will take approximately two 50-minute periods. Overview Students learn about the significance of the founding ideals in the Declaration of Independence and are introduced to the Essay Writing Program. Preview Students respond to and discuss a “Survey on American Ideals.” Reading Students read about and discuss the origins and significance of the five founding ideals: equality, rights, liberty, opportunity, and democracy. Activity In a Writing for Understanding activity, students examine 18 placards, which contain images and quotations spanning American history, to discover the influence of the five founding ideals of the Declaration of Independence. Students then write a five-paragraph essay on the question, Have Americans lived up to the ideals expressed in the Declaration of Independence? Processing The five-paragraph essay functions as this lesson’s Processing assignment. Objectives Students will • investigate the Essential Question: What are America’s founding ideals, and why are they important? • read and analyze primary and secondary sources to understand the meaning and significance of the five founding ideals. • write a five-paragraph essay analyzing how well Americans have lived up to the ideals in the Declaration of Independence. • learn and use the Key Content Terms for this lesson. Vocabulary Key Content Terms equality, rights, liberty, opportunity, democracy Social Studies Terms ideal, self-evident, social class, natural rights, monarchy, dictatorship 12 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Procedures 1 Before class, prepare materials. • Post Information Master A: Ideals and Definitions in the classroom or make copies to be distributed to the class. • Arrange Placards A–R: Introduction to History about 3 to 4 feet apart, either on the classroom walls or someplace with more room, such as a hallway or the cafeteria. 2 Distribute a copy of the Notebook Guide to each student. Give students time to complete the Preview assignment in their notebooks. 3 Discuss student responses to the Preview assignment. Have volunteers share their responses with the class or have students pair up and share with a partner. This Preview is not designed to lead students to any predetermined conclusions but to encourage discussion and debate. 4 Review the five ideals and their definitions on Information Master A. Tell students that each question on the “Survey on American Ideals” relates to one of the five ideals on Information Master A. Review each ideal. Explain that an ideal is different from an idea: an idea can be just about anything that pops into one’s head, whereas an ideal is something truly outstanding that one strives for. 5 Explain the purpose of this lesson. Tell students that in this lesson they will learn about the five ideals, including where they came from and why they are so important to Americans. Students will also begin the Essay Writing Program for this course by writing a five-paragraph essay in response to the question, Have Americans lived up to the ideals expressed in the Declaration of Independence? 13 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Preview 1 Introduce the Essential Question. In your presentation, project Draft of the Declaration of Independence. Have students locate the photograph and Essential Question at the beginning of this lesson. Ask, • What do you see here? • What are some observations you can make about the document? • Why are parts of the document scratched out? What do the scratches tell you about the document? • What document is this? • Where in the document can you find references to each of the five founding ideals: equality, rights, liberty, opportunity, and democracy? (Note: All of these ideals are referred to in the quotation in Section 1, The First Founding Ideals: Equality. They can also be located on Draft of the Declaration of Independence. 2 Read aloud the Essential Question: What are America’s founding ideals, and why are they important? Discuss, explain, or clarify the question as appropriate. 3 Introduce the Key Content Terms and social studies terms for this lesson. Preteach the boldfaced vocabulary terms in the lesson, as necessary, before students begin reading. 4 Have students read Sections 1-7 of the Student Text and complete the corresponding Reading Notes. Use the Guide to Reading Notes to review the answers as a class. (Note: You might want to assign the reading as homework.) 14 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | TGuide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Reading 1 Introduce the activity. Tell students that they will examine a series of images and quotations that span American history, from colonial times to today. Each image and quote relates to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence: they demonstrate either a belief in an ideal, a struggle for an ideal, or a con­flict over an ideal. The placards provide an overview of the importance of the ideals throughout American history. They also preview the content students will study in this course. Explain that after they examine the images and quotations, they will write their five-paragraph essays. 2 Put students in mixed-ability pairs. 3 Distribute Student Handout A: Discovering American Ideals in Primary Sources and review the directions. 4 Monitor students as they work on Student Handout A: Discovering American Ideals in Primary Sources. Before students begin working independently with their partners, you might want to model how to complete the notes for one placard. To encourage students to work quickly and with purpose, consider imposing a time limit for each placard and for the entire activity. If class time is limited, students do not need to complete all the placards. Tell students that after a specified time, they will become an “expert” on the most recent placard they completed. As such, they might be asked to share their expertise with the class. 5 Use a human timeline to debrief the activity. After the specified time, ask students to complete their notes for their current placard and then have them remove the placard from the wall. Assign one student from each pair to be the “expert” for that placard. Everyone else should sit down. Tell the student experts to organize themselves in chronological order, holding the placards in front of their chests so everyone in class can see them. Have the experts per­form the following tasks, as appropriate: • Ask students to step forward if their placard relates to equality in any way. Repeat this for each remaining ideal: rights, liberty, opportunity, and democracy. Discuss why some ideals appear more often than others. • Ask students to step forward if their placard illustrates events or ideas that moved the nation toward the ideals in the Declaration. Ask several students to explain how it shows this. • Ask students to step forward if their placard illustrates events or ideas that moved the nation away from the ideals in the Declaration. Ask several students to explain how it shows this. • Ask students to step forward if they believe their placard shows that Amer icans do live up to the ideals in the Declaration. Ask several students to explain how it shows this. Repeat with examples of how Americans do not live up to the ideals in the Declaration. 15 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | TGuide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Writing for Understanding that during the course of the year, they will learn and practice the elements of writing a five-paragraph essay. They will write four essays in conjunction with four particular lessons and will practice key elements of essay writing throughout the rest of the year. Project Information Master B: Writing an Essay About American Ideals Today and introduce the essay requirements. (Note: The results of this assignment can be used as a baseline to measure individual students’ writing abilities at the start of the year.) 7 Distribute Student Handout B: Graphic Organizer for a Five-Paragraph Essay. Explain that this graphic organizer will help students organize their thoughts and ideas for their essays. Briefly review the graphic organizer with students and make sure they understand what to do for each step. Give stu­dents time to complete their graphic organizers. 8 Have students use notes from their graphic organizer to write a draft of their essays. Have students complete their drafts either in class or for home­work. (Note: Depending on how much time you want to spend on this first essay, you may want to teach or reinforce specific steps in the writing process, such as revising and editing. The Writing Toolkit has specific handouts you can use to guide this process.) 16 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning 6 Introduce the Essay Writing Program and the first writing assignment. Tell students N O T E B O O K G U I D E What Is History? What is history, and why should we study it? K e y C o n t e n t T e r m s As you complete the Reading Notes, use these Key Content Terms in your answers: evidence point of view primary source historical interpretation Section 3 What are the four reasons for studying history? List and rank them from 1 to 4—number 1 represents the reason that is most important and number 4 represents the reason that is least important. Write a brief explanation of why you chose your top ranking. secondary source P R O C E S S I N G R E A D I N G N O T E S Read Sections 2 to 3. After reading each section, complete the following activities in your notebook. Section 2 Copy the following table into your notebook. Use the information from the reading to write a definition for each term in the table. Then explain how each term was represented during the in-class activity. Definition Evidence Primary source Secondary source In-Class Activity Create a timeline of your life from the time you were born to the age you are now. 1. Draw a timeline, with a mark for each year of your life. 2. Use one color to write the three most important events of your life on the timeline. Label each event with your age and a brief description of what happened and why it was important. 3. Ask family members what they think are the three most important events of your life. Use a different color to place those events on the timeline. Label each event with your age and a brief description of what happened and why they think it was important. 4. Beneath the timeline, write a reflection that describes the similarities and differences between the events you chose and those your family chose. Explain why you think you and your family members interpreted the past similarly or differently. Point of view Historical interpretation © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute 17 What Is History? 1 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Notebook Guide G U Í A D E E S T U D I O ¿Qué es la historia? ¿Qué es la historia y por qué debemos estudiarla? P a l a b r a s C l a v e A medida que completes las Notas de la lectura, usa estas Palabras clave en tus respuestas: evidencia punto de vista fuente primaria interpretación histórica fuente secundaria N O T A S Sección 3 ¿Cuáles son las cuatro razones para estudiar historia? Anótalas y ordénalas del 1 al 4; 1 representa la más importante y 4 representa la menos importante. Escribe una explicación breve de por qué elegiste ese orden. P R O C E S A R D E L A L E C T U R A Lee las Secciones 2 a 4. Después de leer cada sección, completa las siguientes actividades en tu cuaderno. Sección 2 Copia la siguiente tabla en tu cuaderno. Usa la información de la lectura para escribir una definición para cada término de la tabla. Después, explica cómo se representó cada término durante la actividad en clase. Definición Evidencia Fuente primaria Fuente secundaria Actividad en clase Crea una línea cronológica de tu vida desde que naciste hasta la edad que tienes ahora. 1. Dibuja una línea cronológica con una marca para cada año de tu vida. 2. Usa un color para escribir los tres sucesos más importantes de tu vida en la línea cronológica. Rotula cada suceso con tu edad y una breve descripción de lo que sucedió y por qué fue importante. 3. Pregúntale a los miembros de tu familia cuáles creen que son los tres sucesos más importantes de tu vida. Usa un color diferente para ubicar esos sucesos en la línea cronológica. Rotula cada suceso con tu edad y una breve descripción de lo que sucedió y por qué creen que fue importante. 4. Debajo de la línea cronológica, escribe una reflexión que describa las similitudes y diferencias entre los sucesos que elegiste tú y aquellos que eligió tu familia. Explica por qué crees que tú y los miembros de tu familia interpretaron el pasado de modo similar o diferente. Punto de vista Interpretación histórica © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute 18 ¿Qué es la historia? 1 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Spanish Notebook Guide G u i d e t o R e a d i n G Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Guide to Reading Notes n o t e s Following are possible answers for each section of the Reading Notes. Section 1 1. These ideals are found in the following phrases: Equality: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” Rights: “That they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.” Liberty: “That among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Opportunity: “That among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Democracy: “That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” 2. The Declaration expresses important ideals that have inspired and challenged Americans for more than 200 years. 3. The ideals were familiar to Americans of the time and had been written about and discussed in the years leading up to the Declaration. Sections 2 to 6 Ideal and Excerpt from the Declaration of Independence Equality “All men are created equal.” Influence of the Ideal in 1776 and Today Definition The ideal situation in which all people are treated the same and valued equally 1776: Christianity taught that all people are equal in God’s eyes. The colonists rejected the inequality found in Europe. Still, some held slaves, and women were treated unequally. Today:Progress has been made in expanding equality, but some argue that “equality of condition” needs to be provided to all. Rights “They are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.” © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute 19 Powers or privileges granted to people either by an agreement among themselves or by law 1776: Jefferson argued in favor of natural, or universal, rights belonging to all humankind. Today: Americans have many rights that are found in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. However, some people still argue for an expansion of rights. defining and debating america’s Founding ideals 1 t o R e a d i n G Ideal and Excerpt from the Declaration of Independence Liberty “That among these [rights] are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” n o t e s Influence of the Ideal in 1776 and Today Definition Liberty can mean different things: • political freedom • civil liberty • moral and religious freedom • the opposite of slavery Opportunity “That among these [rights] are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Democracy “That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” The chance for people to pursue their hopes and dreams 1776: Liberty was extremely important to the colonists, and they fought for freedom from Great Britain. However, one fifth of the population was enslaved. Today: Americans agree that liberty provides the ability to make choices and that limits must be placed on those choices. Americans debate about where to set those limits. 1776: Americans held a strong belief in opportunity from the early colonial period. Opportunity encouraged new settlers. Today: Opportunity still brings newcomers, but some wonder whether true opportunity is available to all. A system of government based on the consent of the governed 1776: Americans used democracy on a local level throughout the colonial period. Yet some wondered whether democracy could work on a larger scale and who should speak for “the governed.” Today: All citizens over the age of 18 can now vote, yet not everyone participates. © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute 20 defining and debating america’s Founding ideals 2 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning G u i d e To protect the integrity of assessment questions, this feature has been removed from the sample lesson. These videos will help you learn more about our print and online assessment tools. Creating Printable Assessments (2:33 min) Creating Online Assessments (2:25 min) 21 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Assessment English Language Learners Provide an alternative Preview assignment. • Before beginning the Preview, bring students’ attention to Information Master A. Ask them to write each word and its definition on one of five separate cards, which you provide or which they make from notebook paper. • On index cards, create a class set of simple, clear symbols for each word. Have students match the symbols with the words and then have them draw the symbols on their cards. • Put students into mixed-ability pairs. Ask each pair of students to rank the ideals according to how important they are to Americans. Ask, Which ideal is most important? Least important? (Note: There are no right or wrong answers. Students should base their rankings on their own beliefs and experience.) • Discuss and debate the following questions, using student cue cards: Which of these ideals does America stand for most? Least? Do you think some Americans would fight and die for any of these ideals? If so, which ones? Which ones would you be willing to die for? Allow some students to respond nonverbally by choosing cards, pointing, or using short phrases. Encourage students who are more fluent to respond in complete sentences. Learners Reading and Writing Below Grade Level Option 1 Create a visual of Student Handout B: Graphic Organizer for a Five-Paragraph Essay. Review the graphic organizer and provide a concrete example for each step. Have students brainstorm additional evidence in small groups or as a class. List student responses on the visual and edit as necessary. Option 2 Instead of completing the entire graphic organizer on Student Handout B: Graphic Organizer for a Five-Paragraph Essay, have students write a thesis statement and complete the steps for body paragraph 1. Modify the requirements on Information Master B, and have students write a paragraph that answers this question: Have Americans lived up to the ideals expressed in the Declaration of Independence? Tell students their paragraph must include (1) a strong topic sentence that states their view and tells the reader what the paragraph is about, (2) at least two pieces of evidence supporting their view, and (3) at least two sentences explaining how their evidence supports their topic sentence. 22 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Differentiating Instruction Concentrate on those placards with the strongest visual components. Make sure all students can view the placards well enough to complete the activity. Advanced Learners On April 3, 1917, William Tyler Page, a clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives, wrote “The American Creed” (reprinted below) as part of an essay writing contest. Provide “The American Creed” for students to read. Define a creed as a statement of belief. Ask students to use what they learned in this lesson about the Declaration’s ideals to write their own creed for all Americans. Then ask them to think beyond the Declaration to how Americans act and behave today. Have them write a second creed that answers this question: What does America really stand for? Require students to write a paragraph explaining the difference between their two creeds. The American Creed I believe in the United States of America as a government of the people, by the people, for the people; whose just powers are derived from the con­sent of the governed, a democracy in a republic, a sovereign Nation of many sovereign States; a perfect union, one and inseparable; established upon those principles of freedom, equality, justice, and humanity for which American patriots sacrificed their lives and fortunes. I therefore believe it is my duty to my country to love it, to support its Constitution, to obey its laws, to respect its flag, and to defend it against all enemies. —William Tyler Page, clerk for the U.S. House of Representatives, 1917 23 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Learners with Special Education Needs Primary Sources for Civic Learning You may wish to have students investigate primary source documents relevant to this lesson. The “Our Documents” initiative is a cooperative effort of the National Archives and Records Administration, National History Day, and the USA Freedom Corps. At its Web site, www. ourdocuments.gov, you can download images and transcripts of the 100 milestone documents chosen for the initiative, along with teaching tools and resources. The documents most relevant to this lesson are the following: The Declaration of Independence, 1776 On July 19, 1776, Congress ordered an engrossed, or handwritten, copy of the Declaration on parchment. It is now one of our treasured Charters of Freedom on display at the National Archives. Original Design of the Great Seal of the United States, 1782 It took three committees to develop the winning design for the Great Seal, which is still in use today. The seal appears on official government buildings and on the back of the one-dollar bill. Using Technology Use a word-processing program to convert Student Handout B: Graphic Organizer for a FiveParagraph Essay into a template that students can use to guide their writing practice while composing their essays. Before the activity, copy the template to a flash drive and save it in a folder on the computers students will use. In class, use a pro­jector to demonstrate how students can use the template to write and edit their five-paragraph essays. 24 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Enhancing Learning www.justicelearning.org/ The innovative site, Justice Learning: Civic Education in the Real World, takes an issues-based approach to the sometimes-contradictory values and ideals of American democracy. Use the “Constitution Guide” to start your exploration of the site; here, each article of the Constitution is explained in detail. Expand your investigation by clicking on the “Issues” link to explore how the ideals expressed in the Constitution have been applied to such issues as affirmative action, education, voting rights, and women’s rights. Each issue has links to New York Times articles and National Public Radio audio files that will further expand your understanding of the Constitution Reading Like a Historian: Declaration of Independence http://sheg.stanford.edu/declaration-independence In 1776, the Founding Fathers wrote the Declaration of Independence, but historians have disagreed over why the authors created this document. 25 Overview | Student Text | Procedures | Notebook Guide | Guide to Reading Notes | Assessment | Differentiating Instruction | Enhancing Learning Justice Learning: Civic Education in the Real World