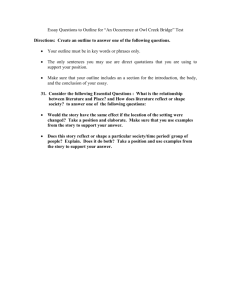

Chapter 2 - Bedford/St. Martin's

advertisement