Essays About 'The Elements of Journalism,' Nieman Reports

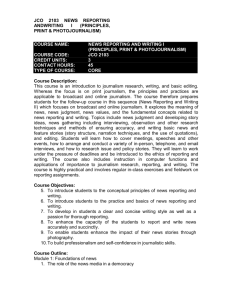

advertisement