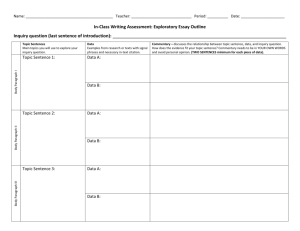

Inquiries Observation Project

advertisement