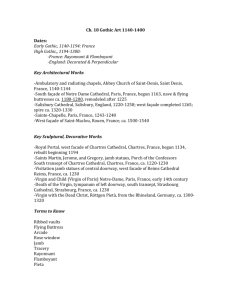

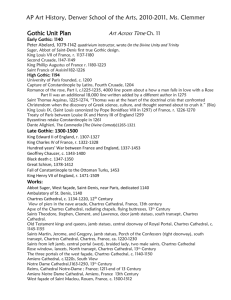

Recent Literature on the Chronology of Chartres Cathedral

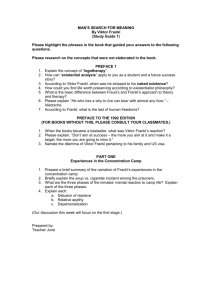

advertisement