Revenue Sharing - George Washington Regional Commission

advertisement

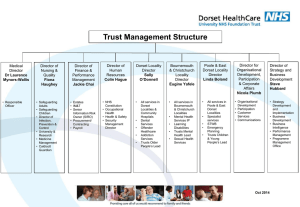

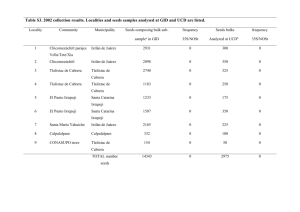

George Washington Regional Commission An Overview of Revenue Sharing Programs in Virginia Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 A. Agreements Subject to Review by Commission on Local Governments ....................................................... 3 1. Voluntary Settlement Agreements ........................................................................................................................... 3 2. Voluntary Economic Growth‐Sharing Agreements ........................................................................................... 4 B. Approaches Exempt from Review by Commission on Local Governments ................................................. 4 C. 1. Regional Industrial Facilities Authorities ............................................................................................................. 4 2. Legislative Enactments ................................................................................................................................................. 5 3. Joint Exercise of Powers Act ....................................................................................................................................... 5 4. Regional Industrial Development Authorities Act ............................................................................................ 6 Economic Impact .................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Table 1. Summary of Revenue Transfers by Type of Sharing Program and Funding Source ................... 6 Table 2. Major and Minor Inter‐Local Revenue‐Sharing Payments by Type, Funding and Recipient Jurisdictions, FY 2009‐2011 ................................................................................................................................................. 7 APPENDIX A: Virginia Regional Industrial Facility Authority Act ........................................................................... 11 APPENDIX B: Revenue Sharing: An Important Economic Development Tool For Virginia Localities .... 19 Acknowledgements: We want to recognize and express appreciation for the contributions of Ted McCormack with VACo and former Director of the Virginia Commission on Local Government, and Susan Williams, current Local Government Policy Manager with the Commission on Local Government, for their assistance in providing historical and current information about revenue‐sharing programs in Virginia. 2 INTRODUCTION Revenue sharing1, achieved through many alternative forms of inter‐governmental agreement, has been found to provide a mechanism to foster regional and inter‐governmental cooperation to promote economic and community development. Researchers have recognized three primary forms of revenue sharing: state, metropolitan and local. State revenue‐sharing, exemplified in many forms (e.g. state aid for education, roads, corrections, etc.) is considered outside the purview of this summary. Metropolitan revenue‐sharing is fairly uncommon and is notably exemplified by the tax base growth revenue sharing program in the Minneapolis‐St. Pail, MN metropolitan area which has “… the most mature program of metropolitan revenue sharing in the United States which was started in 1975. Other variations of this metropolitan effort have also been developed and are operating in Rochester, NY; Hackensack Meadows, NJ; Dayton, OH, and elsewhere, all with their respective merits and lessons learned.”2 However, the metropolitan approach is also considered beyond the purview of this study, partially because Virginia localities and metro areas lack the enabling legislation from the Virginia General Assembly to implement such an approach, or would need to have a series of local referendums to authorize a long‐term debt obligation between counties and cities within such a “metropolitan” revenue‐sharing region. Local revenue sharing, as the primary focus of this report, has been practiced in Virginia under many forms of implementation since at least 1983. Revenue‐sharing agreements associated with annexation disputes, political boundary adjustments or those that function as voluntary growth‐sharing agreements all fall under the purview of the Virginia Commission on Local Government3. These types of agreements, and reference examples of each, are summarized below in Section I. Table 2, which appears before the Appendices, summarized the types of agreements, the major terms of each agreement and the recent history of transfer payments affected by the revenue‐sharing provisions of each agreement. A. Agreements Subject to Review by Commission on Local Governments 1. Voluntary Settlement Agreements Localities are authorized to include provisions establishing long‐term revenue‐sharing arrangements in inter‐local agreements used to settle annexation or other boundary change or governmental transition issues. Since 1983, such agreements require formal review by the Commission on Local Government and approval by a special three‐judge court before they may be implemented. If the agreement calls for the sharing of revenues from a county to a municipality, it is considered a long‐ term general obligation debt and the question must be approved by county voters. (Code, §§15.2‐3400 and 15.2‐3401). The 1987 passage of Virginia legislation imposing a moratorium (expiring in 2018, unless extended by the General Assembly) on annexations of county land area and tax base by cities in Virginia dramatically changed inter‐governmental (city‐county) relationships.4 A partial list of annexation‐related revenue sharing agreements includes: 1 John S. West and Carter Glass IV, Revenue Sharing: An Important Economic Development Tool for Virginia Localities, Virginia Lawyer, the official publication of the Virginia State Bar, April 2000, describes the genesis and effects, somewhat limited, of local revenue sharing programs throughout Virginia. (Re‐printed here as Appendix B). 2 Regionalist Paper No. 12: “Revenue Sharing as a Component of Regionalism‐ What are the Issues?”, see: http://fhrinc.org/Sections/Publications/RegionalistPapers/index.html 3 See http://www.dhcd.virginia.gov/index.php/commission‐on‐local‐government/about‐the‐commission.html 4 See: http://www.coopercenter.org/publications/VANsltr0112 3 City of Charlottesville‐Albemarle County (1983); City of Franklin‐Isle of Wight County (1987); City of Franklin‐Southampton County (1986, 2000); City of Lexington‐Rockbridge County (1987); City of Radford‐Montgomery County (1993); Town of Hillsville‐Carroll County (1996); Bedford County & Bedford City (1997); City of Bedford‐Bedford County (1998); City of Bristol‐Washington County (1999); Town of Vinton‐Roanoke County (2000). 2. Voluntary Economic Growth­Sharing Agreements Localities are also authorized to enter into voluntary economic growth‐sharing agreements for purposes other than the settlement of a boundary change or transition issue, subject only to an advisory review by the Commission on Local Government. If the agreement calls for the sharing of revenues from a county to a municipality, it is considered a long‐term general obligation debt and the question must be approved in a local referendum vote by county voters. (Code of Virginia, §15.2‐ 1301). While there may be others, GWRC staff was only able to identify one example of a voluntary economic growth‐sharing agreement (i.e. Town of Christiansburg‐Montgomery County (2009)). B. Approaches Exempt from Review by Commission on Local Governments 1. Regional Industrial Facilities Authorities In 1997, the Virginia General Assembly passed Senate Bill 1019, enacting the Virginia Regional Industrial Facilities Act. This law has been modified 7 times5 since it was first enacted. Localities are authorized to enter into revenue and economic growth‐sharing agreements with respect to revenues generated by an industrial park owned by a regional industrial facility authority (RIFA). Such regional industrial facility authorities and revenue sharing may be established pursuant solely to action by the governing bodies of the participating localities. (Code, §15.2‐6400 et seq.). This is a partial list of RIFA entities established in Virginia since 1997: Virginia’s First RIFA [Bland, Craig, Giles, Montgomery, Roanoke, Pulaski, and Wythe Counties; the Cities of Roanoke, Radford, and Salem; and the Towns of Christiansburg, Dublin, Narrows, Pearisburg, and Pulaski] (1998); Crossroads RIFA [Bland and Wythe Counties and the Town of Wytheville] (1999); Smyth‐Washington RIFA (2000); Virginia Heartland RIFA (Counties of Amelia, Brunswick, Charlotte, Cumberland, Lunenburg, and Prince Edward) (2000); Virginia Lakeside Commerce Park (Towns of Chase City & Clarksville, County of Mecklenburg) (2000) Danville‐Pittsylvania RIFA (2001); Carroll, Grayson, Galax RIFA (City of Galax & Counties of Carroll and Grayson) (2002) 5 Those modifications are cataloged by “The Acts of Assembly,” a state publication, by year and chapter. Those modifications are as follows: in 1999, chapters 540, 804, 820, 837, 882; in 2000, chapters 892, 915, 960, 965; in 2001, chapters 391, 404; in 2003 chapter 874; in 2004, chapters 603, 640; in 2007, chapters 941, 947; in 2009 chapter 616. 4 Legal researchers (and the Virginia Attorney General) have opined that the provisions of the RIFA legislation that allow counties to enter into a long‐term debt obligation to share revenues with a municipality without a local referendum under a RIFA agreement violate the Virginia Constitution.6 2. Legislative Enactments In the past, the General Assembly has enacted statutes that contain revenue‐sharing provision for specific localities. Examples of these include: Alleghany Highlands Economic Development Authority [Town of Clifton Forge‐Alleghany County] (Code, §15.2‐6200 et seq.); City of Radford‐Pulaski County (Ch. 316, Acts of the Assembly, 1978). 3. Joint Exercise of Powers Act Any local government may enter into an agreement with any other political subdivision of the Commonwealth to exercise jointly any power, privilege, or authority the local government possesses, including the appropriation of funds for a joint undertaking. Such agreements require only the approval of the participating localities. (Code, §15.2‐1300) Roanoke County‐Botetourt County (1988); Cities of Buena Vista and Lexington‐Rockbridge County (1997); Patriot Center Revenue Sharing (City of Martinsville & Henry Co); and City of Lynchburg‐Campbell County (2005). A review of one example is illustrative of the potential shortcomings to this approach. The Rockbridge Area Economic Development Commission (RAEDC) was created in 1980, later re‐named The Rockbridge Partnership, as an instrument of a joint exercise of powers agreement. After several years of debate about the benefits of the program, the City of Buena Vista decided to withdraw from the Partnership. Lexington and Rockbridge County later determined that the Partnership should be abolished and that each jurisdiction would manage its own economic development initiatives. The Partnership was formally disbanded in 2009. Thus this attempt at a regional economic development approach lasted about three decades. Since 2009, Lexington, Buena Vista, and Rockbridge County have managed their own economic development efforts. An ad hoc committee composed of the manager or administrator of each jurisdiction as well as the city/county staff person assigned to conduct that locality's program serve as the core of area economic development efforts. These paid staff are joined by representatives from the Chamber of Commerce (the Chamber), the Regional Tourism Program, the Shenandoah Valley Partnership (SVP), and Central Shenandoah Planning District Commission (CSPDC), to ensure coordination among the governments and other regional agencies in economic development. 6 See Glass & West discussion of RIFAs, page 19 of this report. Apparently, attorney Jim Cornwell, with the SandsAnderson law firm office in Radford, has devised a process that has enabled other RIFAs to form without concern for the noted constitutional limitation. Contact: JCornwell@SandsAnderson.com; (540) 260‐9011, SandsAnderson, 150 Peppers Ferry Rd NE, Christiansburg, VA 24073 5 4. Regional Industrial Development Authorities Act Localities also have the option to form a regional industrial development authority (IDA) as provided under the Code of Virginia7 by having their existing local industrial development authorities jointly act to create a regional authority (effectively merging) for their mutual benefit. The potential for this option to affect revenue sharing is unclear as it would depend upon the circumstances of the powers given to the original authorities and whether any local referendum might be needed to approve tax revenues being re‐distributed beyond the service area of the component local IDAs incurring local‐ term obligation on behalf of the larger regional area and affecting a transfer of revenue to municipalities therein. GWRC staff were unable to identify any such regional IDA created by joint action of existing local IDAs and their corresponding local governments. C. Economic Impact Table 1 summarizes the revenue transfers over the last several years among all the various mechanisms to affect inter‐governmental revenue‐sharing. Greater detail on individual agreement results is provided in Table 2. Table 1. Summary of Revenue Transfers by Type of Sharing Program and Funding Source Agreement Type Annexation-Related/Reviewed by CLG Economic Growth-Sharing Regional Industrial Facilities Authority VA Legislative Enactments Joint Exercise of Powers Payment in Lieu of Taxes Funding Source Jurisdiction County Total City Total Town Total Statewide Total $ $ $ $ $ $ $ FY 2009 16,280,848 772,888 2,304,433 78,380 272,459 890 19,709,899 $ $ $ $ $ $ $ FY 2010 20,835,003 817,786 2,404,449 66,940 352,342 1,985 24,478,505 $ $ $ $ $ $ $ FY 2011 20,561,670 830,993 2,612,796 47,330 180,268 1,170 24,234,227 $ $ $ $ 3,185,183 16,251,367 273,349 19,709,899 $ $ $ $ 3,306,229 20,817,949 354,327 24,478,505 $ $ $ $ 3,491,119 20,561,670 181,438 24,234,227 Source: Virginia Commission on Local Government, Fiscal Stress Index calculations based on data submitted by local governments. Agreement type summary compiled by GWRC staff. See Table 2 for full detail. 7 § 15.2‐4916. Authorities acting jointly. The powers herein conferred upon authorities created under this chapter may be exercised by two or more authorities acting jointly. Two or more localities may jointly create an authority, in which case each of the directors of such authority shall be appointed by the governing body of the respective locality which the director represents. 6 APPENDIX A: Virginia Regional Industrial Facility Authority Act § 15.2­6400. Definitions. As used in this chapter the following words have the meanings indicated: "Authority" means any regional facility authority organized and existing pursuant to this chapter. "Board" means the board of directors of an authority. "Facility" means any structure or park, including real estate and improvements as applicable, for manufacturing, warehousing, distribution, office, or other industrial, residential, recreational or commercial purposes. A facility specifically includes structures or parks that are not owned by an authority or its member localities, but are subject to a cooperative arrangement pursuant to subdivision 13 of § 15.2‐6405. "Governing bodies" means the boards of supervisors of counties and the councils of cities and towns which are members of an authority. "Member localities" means the counties, cities, and towns, or combination thereof, which are members of an authority. "Region" means the area within the boundaries of the member localities. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1710; 1999, cc. 540, 804, 820, 837, 882; 2000, cc. 892, 915, 960, 965; 2001, cc. 391, 404; 2003, c. 874; 2004, cc. 603, 640; 2007, cc. 941, 947; 2009, c. 616.) § 15.2­6401. Findings; purpose; governmental functions. A. The economies of many localities within the region have not kept pace with those of the rest of the Commonwealth. Individual localities in the region often lack the financial resources to assist in the development of economic development projects. Providing a mechanism for localities in the region to cooperate in the development of facilities will assist the region in overcoming this barrier to economic growth. The creation of regional industrial facility authorities will assist this area of the Commonwealth in achieving a greater degree of economic stability. B. The purpose of a regional industrial facility authority is to enhance the economic base for the member localities by developing, owning, and operating one or more facilities on a cooperative basis involving its member localities. C. The exercise of the powers granted by this chapter shall be in all respects for the benefit of the inhabitants of the region and other areas of the Commonwealth, for the increase of their commerce, and for the promotion of their safety, health, welfare, convenience and prosperity. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1711.) § 15.2­6402. Procedure for creation of authorities. The governing bodies of any three or more localities within the region, provided that two or more of the localities are cities or counties or a combination thereof, may, in conformance with the procedure set forth herein, create a regional industrial facility authority by adopting ordinances proposing to create an authority which shall: (i) set forth the name of the proposed regional industrial facility authority (which shall include the words "industrial facility authority"); (ii) name the member localities; (iii) contain findings that the economic growth and development of the locality and the comfort, convenience and welfare of its citizens require the development of facilities and that joint action through a regional industrial facility authority by the localities which are to be members of the proposed authority will facilitate the development of the needed facilities; and 11 (iv) authorize the execution of an agreement establishing the respective rights and obligations of the member localities with respect to the authority consistent with the provisions of this chapter. However, with regard to Planning Districts 2, 3, 10, 11 and 12, the governing bodies of any two or more localities within the region, provided that one or more of the localities is a city or county, may adopt such an ordinance. Such ordinances shall be filed with the Secretary of the Commonwealth. Upon certification by the Secretary of the Commonwealth that the ordinances required by this chapter have been filed and, upon the basis of the facts set forth therein, satisfy such requirements, the proposed authority shall be and constitute an authority for all of the purposes of this chapter, to be known and designated by the name stated in the ordinances. Upon the issuance of such certificate, the authority shall be deemed to have been lawfully and properly created and established and authorized to exercise its powers under this chapter. Each authority created pursuant to this chapter is hereby created as a political subdivision of the Commonwealth. At any time subsequent to the creation of an authority under this chapter, the membership of the authority may, with the approval of the authority's board, be expanded to include any locality within the region that would have been eligible to be an initial member of the authority. The governing body of a locality seeking to become a member of an existing authority shall evidence its intent to become a member by adopting an ordinance proposing to join the authority that conforms, to the extent applicable, to the requirements for an ordinance set forth in clauses (i), (iii), and (iv) of this section. 1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1712; 1999, cc. 820, 882; 2000, c. 892; 2001, c. 391; 2002, c. 691; 2006, c. 324.) § 15.2­6403. Board of the authority. A. All powers, rights and duties conferred by this chapter, or other provisions of law, upon an authority shall be exercised by a board of directors. A board shall consist of two members for each member locality. The governing body of each member locality shall appoint two members to the board. Any person who is a resident of the appointing member locality may be appointed to the board. However, if an authority has only two member localities, the governing body of each locality may appoint three members each. However, in any instance in which the member localities are not equally contributing funding to the authority, and upon agreement by each member locality, the number of appointments to be made by each locality may be based upon the percentage of local funds contributed by each of the member localities. Each member of a board shall serve for a term of four years and may be reappointed for as many terms as the governing body desires. However, the board may elect to provide for staggered terms, in which case some members may draw an initial two‐year term. If a vacancy occurs by reason of the death, disqualification or resignation of a board member, the governing body of the member locality that appointed the authority board member shall appoint a successor to fill the unexpired term. However, with regard to any authority created by Planning Districts 10, 11 and 12, only members of the appointing governing body of each member locality shall be appointed to the board. In the event such board members feel it is necessary to have an odd number of members, they may establish a rotation system that will allow one locality to appoint one extra member to serve for up to two years. Each locality will, in turn, appoint such extra member. Once the cycle is completed, the rotation shall be repeated. Each member locality may appoint up to two alternate board members. Alternates shall be selected in the same manner as board members, and may serve as an alternate for either board member from the member locality that appoints the alternate. Alternates shall be appointed for terms that coincide with one or more of the board members from the member locality that appoints the alternate. If a board member is not present at a meeting of the authority, the alternate shall have all the voting and other rights of the board member not present and shall be counted for purposes of determining a quorum. Alternates are required to take an oath of office and are entitled to reimbursement for expenses in the same manner as board members. B. Each member of a board shall, before entering upon the discharge of the duties of his office, take and subscribe to the oath prescribed in § 49‐1. Members shall be reimbursed for actual expenses incurred in the performance of their duties from funds available to the authority. C. A quorum shall exist when a majority of the member localities are represented by at least one member of the board. The affirmative vote of a quorum of the board shall be necessary for any action taken by the board. No vacancy in the membership of a board shall impair the right of a quorum to exercise all the rights and perform all 12 the duties of the board. The board shall determine the times and places of its regular meetings, which may be adjourned or continued, without further public notice, from day to day or from time to time or from place to place, but not beyond the time fixed for the next regular meeting, until the business before the board is completed. Special meetings of a board shall be held when requested by members of the board representing two or more localities. Any such request for a special meeting shall be in writing, and the request shall specify the time and place of the meeting and the matters to be considered at the meeting. A reasonable effort shall be made to provide each member with notice of any special meeting. No matter not specified in the notice shall be considered at such special meeting unless all the members of the board are present. Special meetings may be adjourned or continued, without further public notice, from day to day or from time to time or from place to place, not beyond the time fixed for the next regular meeting, until the business before the board is completed. D. Each board shall elect from its membership a chairman for each calendar year. The board may also appoint an executive director and staff who shall discharge such functions as may be directed by the board. The executive director and staff shall be paid from funds received by the authority. E. Each board, promptly following the close of the fiscal year, shall submit an annual report of the authority's activities of the preceding year to the governing body of each member locality. Each such report shall set forth a complete operating and financial statement covering the operation of the authority during such year. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1713; 1999, cc. 820, 882; 2000, c. 892; 2001, cc. 7, 15, 390, 391; 2002, c. 691; 2006, c. 758.) § 15.2­6404. Office of authority; title to property. Each board shall maintain the principal office of the authority within a member locality. All records shall be kept at such office. The title to all property of every kind belonging to an authority shall be titled to the authority, which shall hold it for the benefit of its member localities. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1714.) § 15.2­6405. Powers of the authority. Each authority is vested with the powers of a body corporate, including the power to sue and be sued in its own name, plead and be impleaded, and adopt and use a common seal and alter the same as may be deemed expedient. In addition to the powers set forth elsewhere in this chapter, an authority may: 1. Adopt bylaws, rules and regulations to carry out the provisions of this chapter; 2. Employ, either as regular employees or as independent contractors, consultants, engineers, architects, accountants, attorneys, financial experts, construction experts and personnel, superintendents, managers and other professional personnel, personnel, and agents as may be necessary in the judgment of the authority, and fix their compensation; 3. Determine the locations of, develop, establish, construct, erect, repair, remodel, add to, extend, improve, equip, operate, regulate, and maintain facilities to the extent necessary or convenient to accomplish the purposes of the authority; 4. Acquire, own, hold, lease, use, sell, encumber, transfer, or dispose of, in its own name, any real or personal property or interests therein; 5. Invest and reinvest funds of the authority; 6. Enter into contracts of any kind, and execute all instruments necessary or convenient with respect to its carrying out the powers in this chapter to accomplish the purposes of the authority; 7. Expend such funds as may be available to it for the purpose of developing facilities, including but not limited to (i) purchasing real estate; (ii) grading sites; (iii) improving, replacing, and extending water, sewer, natural gas, electrical, and other utility lines; (iv) constructing, rehabilitating, and expanding buildings; (v) constructing parking facilities; (vi) constructing access roads, streets, and rail lines; (vii) purchasing or leasing machinery and tools; and (viii) making any other improvements deemed necessary by the authority to meet its objectives; 13 8. Fix and revise from time to time and charge and collect rates, rents, fees, or other charges for the use of facilities or for services rendered in connection with the facilities; 9. Borrow money from any source for any valid purpose, including working capital for its operations, reserve funds, or interest; mortgage, pledge, or otherwise encumber the property or funds of the authority; and contract with or engage the services of any person in connection with any financing, including financial institutions, issuers of letters of credit, or insurers; 10. Issue bonds under this chapter; 11. Accept funds and property from the Commonwealth, persons, counties, cities, and towns and use the same for any of the purposes for which the authority is created; 12. Apply for and accept grants or loans of money or other property from any federal agency for any of the purposes authorized in this chapter and expend or use the same in accordance with the directions and requirements attached thereto or imposed thereon by any such federal agency; 13. Make loans or grants to, and enter into cooperative arrangements with, any person, partnership, association, corporation, business or governmental entity in furtherance of the purposes of this chapter, for the purposes of promoting economic and workforce development, provided that such loans or grants shall be made only from revenues of the authority that have not been pledged or assigned for the payment of any of the authority's bonds, and to enter into such contracts, instruments, and agreements as may be expedient to provide for such loans, and any security therefor. The word "revenues" as used in this subdivision includes grants, loans, funds and property, as set out in subdivisions 11 and 12; 14. Enter into agreements with any other political subdivision of the Commonwealth for joint or cooperative action in accordance with § 15.2‐1300; and 15. Do all things necessary or convenient to carry out the purposes of this chapter. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1715; 2002, c. 691; 2003, c. 874.) § 15.2­6406. Donations to authority; remittance of tax revenue. A. Member localities are hereby authorized to lend or donate money or other property to an authority for any of its purposes. The member locality making the grant or loan may restrict the use of such grants or loans to a specific facility owned by the authority, within or without that member locality. B. The governing body of the member locality in which a facility owned by an authority is located may direct, by resolution or ordinance, that all tax revenue collected with respect to the facility shall be remitted to the authority. Such revenues may be used for the payment of debt service on bonds of the authority and other obligations of the authority incurred with respect to such facility. The action of such governing body shall not constitute a pledge of the credit or taxing power of such locality. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1716; 2004, cc. 42, 603, 640.) § 15.2­6407. Revenue sharing agreements. Notwithstanding the requirements of Chapter 34 (§ 15.2‐3400 et seq.) of this title, the member localities may agree to a revenue and economic growth‐sharing arrangement with respect to tax revenues and other income and revenues generated by any facility owned by an authority. Such member localities may be located in any jurisdiction participating in the Appalachian Region Interstate Compact or a similar agreement for interstate cooperation for economic and workforce development authorized by law. The obligations of the parties to any such agreement shall not be construed to be debt within the meaning of Article VII, Section 10 of the Constitution of Virginia. Any such agreement shall be approved by a majority vote of the governing bodies of the member localities reaching such an agreement but shall not require any other approval. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1717; 2007, cc. 941, 947.) 14 § 15.2­6408. Applicability of land use regulations. In any locality where planning, zoning, and development regulations may apply, an authority shall comply with and is subject to those regulations to the same extent as a private commercial or industrial enterprise. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1718.) § 15.2­6409. Bond issues; contesting validity of bonds. A. An authority may at any time and from time to time issue bonds for any valid purpose, including the establishment of reserves and the payment of interest. In this chapter, "bonds" includes notes of any kind, interim certificates, refunding bonds, or any other evidence of obligation. B. The bonds of any issue shall be payable solely from the property or receipts of the authority, including, but not limited to: 1. Taxes, rents, fees, charges, or other revenues payable to the authority; 2. Payments by financial institutions, insurance companies, or others pursuant to letters or lines of credit, policies of insurance, or purchase agreements; 3. Investment earnings from funds or accounts maintained pursuant to a bond resolution or trust agreement; and 4. Proceeds of refunding bonds. C. Bonds shall be authorized by resolution of an authority and may be secured by a trust agreement by and between the authority and a corporate trustee or trustees, which may be any trust company or bank having the powers of a trust company within or without the Commonwealth. The bonds shall: 1. Be issued at, above, or below par value, for cash or other valuable consideration, and mature at a time or times, whether as serial bonds or as term bonds or both, not exceeding forty years from their respective dates of issue; 2. Bear interest at the fixed or variable rate or rates determined by the method provided in the resolution or trust agreement; 3. Be payable at a time or times, in the denominations and form, and carry the registration and privileges as to conversion and for the replacement of mutilated, lost, or destroyed bonds as the resolution or trust agreement may provide; 4. Be payable in lawful money of the United States at a designated place; 5. Be subject to the terms of purchase, payment, redemption, refunding, or refinancing that the resolution or trust agreement provides; 6. Be executed by the manual or facsimile signatures of the officers of the authority designated by the authority, which signatures shall be valid at delivery even for one who has ceased to hold office; and 7. Be sold in the manner and upon the terms determined by the authority including private (negotiated) sale. D. Any resolution or trust agreement may contain provisions which shall be a part of the contract with the holders of the bonds as to: 1. Pledging, assigning, or directing the use, investment, or disposition of receipts of the authority or proceeds or benefits of any contract and conveying or otherwise securing any property rights; 2. Setting aside loan funding deposits, debt service reserves, capitalized interest accounts, cost of issuance accounts and sinking funds, and the regulation, investment, and disposition thereof; 15 3. Limiting the purpose to which, or the investments in which, the proceeds of the sale of any issue of bonds may be applied and restrictions to investments of revenues or bond proceeds in government obligations for which principal and interest are unconditionally guaranteed by the United States of America; 4. Limiting the issuance of additional bonds and the terms upon which additional bonds may be issued and secured and may rank on a parity with, or be subordinate or superior to, other bonds; 5. Refunding or refinancing outstanding bonds; 6. Providing a procedure, if any, by which the terms of any contract with bondholders may be altered or amended and the amount of bonds the holders of which must consent thereto, and the manner in which consent shall be given; 7. Defining the acts or omissions which shall constitute a default in the duties of the authority to bondholders and providing the rights of or remedies for such holders in the event of a default which may include provisions restricting individual right of action by bondholders; 8. Providing for guarantees, pledges of property, letters of credit, or other security, or insurance for the benefit of the bondholders; and 9. Addressing any other matter relating to the bonds which the authority determines appropriate. E. No member of an authority, member of a board, or any person executing the bonds on behalf of an authority shall be liable personally for the bonds or subject to any personal liability by reason of the issuance of the bonds. F. An authority may enter into agreements with agents, banks, insurers, or others for the purpose of enhancing the marketability of, or as security for, its bonds. G. A pledge by an authority of revenues as security for an issue of bonds shall be valid and binding from the time the pledge is made. The revenues pledged shall immediately be subject to the lien of the pledge without any physical delivery or further act, and the lien of any pledge shall be valid and binding against any person having any claim of any kind in tort, contract or otherwise against an authority, irrespective of whether the person has notice. No resolution, trust agreement or financing statement, continuation statement, or other instrument adopted or entered into by an authority need be filed or recorded in any public record other than the records of the authority in order to perfect the lien against third persons, regardless of any contrary provision of public general or local law. H. Except to the extent restricted by an applicable resolution or trust agreement, any holder of bonds issued under this chapter or a trustee acting under a trust agreement entered into under this chapter, may, by any suitable form of legal proceedings, protect and enforce any rights granted under the laws of Virginia or by any applicable resolution or trust agreement. I. An authority may issue bonds to refund any of its bonds then outstanding, including the payment of any redemption premium and any interest accrued or to accrue to the earliest or any subsequent date of redemption, purchase or maturity of the bonds. Refunding bonds may be issued for the public purposes of realizing savings in the effective costs of debt service, directly or through a debt restructuring, for alleviating impending or actual default and may be issued in one or more series in an amount in excess of that of the bonds to be refunded. J. For a period of thirty days after the date of the filing with the circuit court having jurisdiction over any of the political subdivisions that are members of the authority and in which the facility or any portion thereof being financed is located a certified copy of the initial resolution of the authority authorizing the issuance of bonds, any person in interest may contest the validity of the bonds, the rates, rents, fees and other charges for the services and facilities furnished by, for the use of, or in connection with, the facility or any portion thereof being financed, the pledge of revenues pledged to payment of the bonds, any provisions that may be recited in any resolution, trust agreement, indenture or other instrument authorizing the issuance of bonds, or any matter contained in, 16 provided for or done or to be done pursuant to the foregoing. If such contest is not given within the thirty‐day period, the authority to issue bonds, the validity of any other provision contained in the resolution, trust agreement, indenture or other instrument, and all proceedings in connection with the authorization and the issuance of the bonds shall be conclusively presumed to have been legally taken and no court shall have authority to inquire into such matters and no such contest shall thereafter be instituted. Upon the delivery of any bonds reciting that they are issued pursuant to this chapter and a resolution or resolutions adopted under this chapter, the bonds shall be conclusively presumed to be fully authorized by all the laws of the Commonwealth and to have been sold, executed and delivered by the authority in conformity with such laws, and the validity of the bonds shall not be questioned by a party plaintiff, a party defendant, the authority, or any other interested party in any court, anything in this chapter or in any other statutes to the contrary notwithstanding. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1719; 2002, c. 691.) § 15.2­6410. Investments in bonds. Any financial institution, investment company, insurance company or association, and any personal representative, guardian, trustee, or other fiduciary, may legally invest any moneys belonging to them or within their control in any bonds issued by an authority. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1720.) § 15.2­6411. Bonds exempt from taxation. An authority shall not be required to pay any taxes or assessments of any kind whatsoever, and its bonds, their transfer, the interest payable on them, and any income derived from them, including any profit realized in their sale or exchange, shall be exempt at all times from every kind and nature of taxation by this Commonwealth or by any of its political subdivisions, municipal corporations, or public agencies of any kind. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1721.) § 15.2­6412. Tax revenues of the Commonwealth or any other political subdivision not pledged. Nothing in this chapter shall be construed as authorizing the pledging of the faith and credit of the Commonwealth of Virginia, or any of its revenues, or the faith and credit of any other political subdivision of the Commonwealth, or any of its revenues, for the payment of any bonds issued by an authority. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1722.) § 15.2­6412. Tax revenues of the Commonwealth or any other political subdivision not pledged. Nothing in this chapter shall be construed as authorizing the pledging of the faith and credit of the Commonwealth of Virginia, or any of its revenues, or the faith and credit of any other political subdivision of the Commonwealth, or any of its revenues, for the payment of any bonds issued by an authority. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1722.) § 15.2­6414. Tort liability. No pecuniary liability of any kind shall be imposed on the Commonwealth or on any other political subdivision of the Commonwealth because of any act, agreement, contract, tort, malfeasance or nonfeasance by or on the part of an authority, its agents, servants or employees. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1724.) § 15.2­6415. Dissolution of authority. A member locality of an authority may withdraw from the authority only (i) upon dissolution of the authority as set forth herein, or (ii) with the majority approval of all other members of such authority, upon a resolution adopted by the governing body of a member locality and after satisfaction of such member locality's legal obligations, including repayment of its portion of any debt incurred, with regard to the authority, or after making contractual provisions for 17 the repayment of its portion of any debt incurred, with regard to the authority, as well as pledging to pay general dues for operation of the authority for the current and succeeding fiscal year following the effective date of withdrawal. No member seeking withdrawal shall retain, without the consent of a majority of the remaining members, any rights to contributions made by such member, to any property held by such authority or to any revenue sharing as allowed by §§ 15.2‐6406 and 15.2‐6407. Upon withdrawal, the withdrawing member shall also return to the authority any dues or other contributions refunded to such member during its membership in the authority. Whenever the board determines that the purpose for which the authority was created has been substantially fulfilled or is impractical or impossible to accomplish and that all obligations incurred by the authority have been paid or that cash or a sufficient amount of United States government securities has been deposited for their payment, or provisions satisfactory for the timely payment of all its outstanding obligations have been arranged, the board may adopt resolutions declaring and finding that the authority shall be dissolved. Appropriate attested copies of such resolutions shall be delivered to the Governor so that legislation dissolving such authority may be introduced in the General Assembly. The dissolution of an authority shall become effective according to the terms of such legislation. The title to all funds and other property owned by such authority at the time of such dissolution shall vest in the member localities which have contributed to the authority in proportion to their respective contributions. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1725; 2010, c. 531.) § 15.2­6416. Chapter liberally construed. This chapter, being necessary for the welfare of the Commonwealth and its inhabitants, shall be liberally construed to effect the purposes thereof. (1997, cc. 276, 587, § 15.1‐1726.) 18 APPENDIX B: Revenue Sharing: An Important Economic Development Tool For Virginia Localities Historically, Virginia’s unique and fractured system of local government—with its independent cities and counties— has made regional economic development efforts among Virginia localities extremely rare. In more recent years, however, local government leaders have come to realize that they must find ways to work with neighboring jurisdictions to pool available resources if they are to succeed at bringing new businesses and jobs to their communities. As a result, revenue sharing agreements have emerged as an important tool available to local governments in their efforts to establish successful regional economic development projects. The Urban Partnership and the Virginia Chamber of Commerce have strongly endorsed revenue sharing as a means of promoting cooperation among localities that will make regions within Virginia more competitive in the economic development field. The chamber of commerce has noted that regions that work together are stronger and more successful. Often, a single jurisdiction working alone is not able to attract a business or industry. Furthermore, in many regions of Virginia, counties have the land, while cities have the capital. The chamber of commerce has also reported that without revenue sharing, the benefits of attracting a business prospect to an area may be distributed very unevenly. One locality may reap most of the tax revenue rewards because it has much more land suitable for development, while another locality may absorb most of the added costs for transportation and education services. Background The statutory authority for revenue sharing agreements among Virginia localities was originally enacted as part of the 1979 compromise that resulted in a major revision of the annexation and governmental status provisions of the Virginia Code. Former Virginia Code § 15.1‐1166 and §15.1‐1667 authorized cities and towns to enter into agreements to share in the “benefits of the economic growth of their jurisdictions.” Such an agreement was permitted if a city relinquished its annexation authority for all or any part of an adjacent county or for “any other purpose,” including the regional provision of one or more “public services or facilities.”1 After the moratorium on city annexations was lifted in 1979, revenue sharing was used almost exclusively in a defensive manner as an alternative to annexation. For example, some of the initial agreements using this authority: Charlottesville‐ ‐ Albemarle County, Franklin‐Isle of Wight County, and Lexington‐Rockbridge County—involved a permanent waiver of annexation rights in exchange for a “tax base” sharing. With the reenactment of a city annexation moratorium in 1987 and the increased interest in economic development among all Virginia localities, the focus of revenue sharing arrangements has shifted in recent years to joint efforts to pool resources to compete for commercial and industrial businesses and to share in the revenues generated by such new development. Statutory Authority For Revenue Sharing Two general law provisions grant broad revenue sharing authority to all Virginia localities.2 In addition, several other provisions grant more narrow revenue sharing powers that are applicable to a limited number of jurisdictions.3 Voluntary Settlement Agreements The first broad grant of authority to share revenues established by the General Assembly, and the one most often utilized by localities, is found in Virginia Code §§ 15.2‐3400 through 15.2‐ 3401. Under these two statutes, any two or more localities may enter into an agreement to settle matters involving any annexation or governmental status proceeding provided for in Subtitle III of Title 15.2. As originally enacted in 1983, § 15.2‐3400 authorizes: waiver or modification of annexation, transition, immunity or other rights provided in Subtitle III; fiscal arrangements; revenue and economic growth sharing; dedication of all or any portion of tax revenues to a revenue and economic growth sharing 19 account; boundary line adjustments; acquisition of real property and buildings; and joint exercise or delegation of powers.4 In 1990, an amendment to the statute broadened considerably the scope of such agreements by also permitting the parties to include provisions regarding land use, zoning, subdivision, and infrastructure arrangements, as well as “such other provisions as the parties deem in their best interest.”5 In its present form, the statute gives localities virtually unlimited authority regarding the types of provisions they may include in a settlement, subject to any constitutional limitations, and subject to the court’s determination that the agreement is in the best interests of the parties.6 A previous amendment to the statute also permitted the parties to provide in the agreement for “subsequent court review” by a three‐judge court.7 This language presumably authorizes a mechanism to enforce the terms and conditions of the order approving the agreement, although it might also allow the court to amend or modify the agreement in the future when one of the parties believes certain terms are no longer equitable. Under this statutory scheme, a proposed voluntary settlement agreement must be presented to the Commission on Local Government for review.8 The commission determines whether the proposed settlement is in the “best interests of the Commonwealth,” but its findings and recommendations are only advisory in nature. In reviewing proposed voluntary agreements, the commission has recommended court approval of such settlements in most cases, although it often suggests that the parties make minor modifications to the overall agreements. After the commission has issued its report, the localities may adopt the original agreement or a modified agreement after required public notification and hearing.9 Upon adoption of a voluntary settlement agreement, the localities must petition a three‐judge court for an order establishing the rights of the parties as set forth in the agreement. The statute provides that the court shall approve the agreement unless it finds either that the agreement is contrary to the best interests of the Commonwealth—including the state’s interest in promoting the orderly growth and continued viability of local governments —or that the agreement is not in the best interests of each of the parties. This standard is distinct from the requirements for individual annexation, immunity, incorporation, or transition actions. The court has the authority to either affirm or deny the agreement in its entirety, but it may not amend or alter the terms or conditions without express approval from each of the parties.10 The entry of a court order affirming an agreement makes it binding on future local governing bodies.11 The revenue sharing agreement between the City of Bedford and the County of Bedford in 199712 is a good example of localities pooling their resources to attract new businesses and sharing the resulting revenues. On the one hand, the city had a water and sewer system, but it had little vacant land suitable for a modern industrial/commercial park. On the other hand, the county had no water or sewer facilities in the areas surrounding the city, but had ample vacant land. Under the agreement, the localities agreed to jointly fund utility improvements and other infrastructure for five industrial/commercial parks and share the resulting tax revenues. Their agreement said that: the city agreed to extend its water and sewer lines to four proposed commercial/industrial parks in the county; the city’s obligation to extend its utility lines is limited to the expenses that can be funded by one‐half of the rev‐ enue sharing payments it receives from county parks; the city and the county agreed to share equally most tax revenues generated by the four county parks and one existing park located within the city; the city agreed to pay a joint industrial development authority 50% of the net revenues from the city’s sales of electric power to businesses in the county parks; and, the county’s revenue sharing obligations are subject to annual appropriations by the county; however, if the county elects not to make the payments, the city can immediately annex the four county parks. Revenue sharing arrangements established pursuant to the voluntary settlement statute present certain hurdles that localities must overcome. The most prevalent one involves the constitutional debt limitations imposed on counties. If such an agreement would obligate a county to make 20 payments that constitute debt under Article VII, Section 10(b) of the Virginia Constitution, then Virginia Code § 15.2‐3401 requires that such an arrangement be approved by the qualified voters of the county at a special referendum election before the county enters into the agreement. This Code Section was enacted as a result of “widespread recognition that the obligations of counties under voluntary revenue sharing arrangements establish debt subject to constitutional limitations.”13 transfer one‐half of the tax revenues to the city. Again, the attorney general concluded that the “special fund” exception did not apply to a “fund” consisting of tax revenues Since the enactment of this provision, localities have attempted to structure revenue sharing arrangements to avoid the referendum requirement applicable to counties. Despite their best efforts, the attorney general has opined that most such arrangements were still subject to the constitutional limitations. Two examples illustrate this point. Economic Growth Sharing Agreements An agreement made between the City of Franklin and Isle of Wight County required the county to pay a portion of local tax revenues from a limited geographical area, which contained an existing manufacturing plant. It also required the city to provide certain utility services and to waive its annexation rights. Even though the source of the payments by the county was limited to tax revenues from specific parcels of real property, the attorney general concluded that such an arrangement did not fall within the “special fund” exception to the constitutional debt limitation,14 because the revenues would otherwise have been “available for general county purposes” and did not involve the “type of revenue‐producing, self‐liquidating county project contemplated under that doctrine.”15 Likewise, the provision of certain utility services and the continuing waiver of the city’s right to seek annexation did not fall within the “service contract doctrine” recognized in Virginia, which exempts from the constitutional debt limitations those county financial obligations payable in future installments as a service is rendered. The opinion noted that the amount of tax revenues “significantly exceeded the cost or value of the services provided.”16 An agreement between the City of Clifton Forge and Alleghany County provided for the sale of city owned property to a private industry and the perpetual equal sharing of designated tax revenues generated by facilities to be constructed on the site. Because the property is located in the county, the agreement obligated the county to that the locality was otherwise “obligated to impose and appropriate” for general county purposes. Thus, the county’s obligation to transfer those revenues constituted long‐term debt subject to the constitutional limitations.17 The second statute granting broad revenue sharing powers was enacted by the General Assembly in 1996. Virginia Code § 15.2‐1301 authorizes localities to enter into a “revenue, tax base, or economic growth sharing” agreement that is not a part of an annexation or transition settlement.18 As discussed above, the statutory authority for “voluntary settlements” under Virginia Code § 15.2‐3400 requires some connection with an annexation or governmental status matter, which limits its usefulness for localities that want to provide for revenue sharing outside the scope of any annexation or similar issue. Agreements done pursuant to § 15.2‐1301, however, can be used for “any purpose otherwise permitted,” including the provision of public services or facilities or “any type of economic development project.” This statute permits all forms of revenue sharing. “Revenues” can include non‐tax receipts of a locality such as user fees or state appropriations. “Tax base” can include taxes received from all development, existing and future. “Economic growth sharing” permits an arrangement limited to taxes derived from new development. An agreement reached under Virginia Code § 15.2‐ 1301 enjoys two procedural advantages over those made under the voluntary settlement statute. As with a “voluntary settlement,” the Commission on Local Government performs an advisory review; however, the review can be accelerated because the commission is not required to hold a public hearing or to comply with certain notice requirements. More importantly, § 15.2‐1301 does not require that such an agreement be reviewed or approved by any court. Localities cannot use this procedure, however, if the revenue sharing proposal contains “any provision addressing any issue” relating to 21 annexation, immunity from annexation, incorporation of a new town, transition of a town to city status, transition of a county to a city, or transition of a city to town status. As with a “voluntary settlement,” any growth sharing agreement made pursuant to Virginia Code § 15.2‐1301 that would obligate a county to make payments that constitute debt under Article VII, Section 10(b) of the Virginia Constitution must be approved in a county referendum.19 Virginia Regional Industrial Facilities Act One of the narrower grants of revenue sharing authority is found in Chapter 64 of Title 15.2 of the Virginia Code. Commonly known as the “Virginia Regional Industrial Facilities Act,” the act authorizes the formation of regional industrial facility authorities. Under the act, any three or more qualifying localities (but at least two cities or counties) may create a regional industrial facility that may develop and operate an industrial park to be occupied by manufacturing, warehousing, distribution, office or other commercial businesses. The purpose of such an authority is to permit the localities in that region to cooperate in developing such a park because the individual localities lack the resources to pursue such economic development projects.20 The regional authority may issue bonds for the development of an industrial park.21 The act, however, is applicable only to Planning District 4 (counties of Floyd, Giles, Montgomery, and Pulaski, and the city of Radford), Planning District 5 (counties of Alleghany, Botetourt, Craig, and Roanoke, and the cities of Clifton Forge, Covington, Roanoke, and Salem), Planning District 11 (counties of Amherst, Appomattox, Bedford, and Campbell, and the cities of Bedford and Lynchburg) and Planning District 12 (counties of Franklin, Henry, Patrick, and Pittsylvania, and the cities of Danville and Martinsville), as well as the counties of Bland, Smyth and Wythe.8 The first such authority was created under the act by 15 localities in the qualifying region.22 The plan is that this new authority will allow these localities to proceed with projects, such as a new large industrial 8 GWRC Note: The general geographic limitation to specific Planning Districts no longer applies. park in Pulaski County, that could attract major new industries that currently bypass this region of the state. Because the industrial park or parks authorized by this Act may not be located in each of the participating localities, the statutes provide for a sharing of the tax benefits of a successful project. Virginia Code § 15.2‐1713 authorizes the members to agree to a “revenue and economic growth‐sharing arrangement” as to the tax revenues and other “income and revenues” generated by the industrial park. In addition, the member locality in which a facility is located may remit all machinery and tools tax revenue to the regional authority for payment of debt service of the authority.23 The General Assembly has provided that the obligations of member localities to make such revenue sharing payments “shall not be construed to be debt within the meaning of Article VII, Section 10” of the Virginia Constitution. Such an agreement must be approved by a majority vote of the governing body of each member locality, but “shall not require any other approval.”24 Similarly, the payment of machinery and tools tax revenues “shall not constitute a pledge of the credit or taxing power of such locality.”25 Based on existing opinions of the Virginia Attorney General, there appears to be a substantial question as to the validity of such revenue sharing provisions, especially where a county in which an industrial park is located is unconditionally obligated to make long‐term payments of tax revenues generated by the park. It is doubtful the General Assembly can avoid the constitutional referendum requirements merely by legislating that debt obligations do not constitute debt under the Constitution.26 A regional authority might assert, however, that the “special fund” exception to the constitutional debt limitations is applicable to such obligations, notwithstanding prior opinions by the attorney general. Alternatively, the Supreme Court has ruled that certain “contingent” obligations do not constitute debt under Article VII, Section 1027 and a regional authority might contend that an obligation to share revenues from an industrial park that might never secure an industry or business does not constitute a debt for purposes of the Virginia Constitution. 22 Indirect Revenue Sharing: Water and Sewer Rates In addition to the revenue sharing agreements authorized in the context of voluntary settlements, economic growth sharing arrangements, and through the establishment of regional industrial facilities, the General Assembly has made it possible for certain localities to share revenues indirectly. One of the best examples of such arrangements involves the Town of Front Royal and Warren County. As of 1997, the Town of Front Royal had the only municipal water and sewer service in Warren County. Certain industries and businesses were interested in locating within a portion of the unincorporated area of the county outside the town limits, but needed to have public utility services. The town proposed to extend its facilities outside its boundaries and to charge the businesses using its water/sewer services, in addition to its normal rates, an amount equivalent to the total property taxes and license fees the businesses would be required to pay if they were located within the town. The attorney general acknowledged that the town could charge out‐of‐town customers additional sums to extend Front Royal’s utilities outside its boundaries and to “assume on a continuing basis any additional costs and expenses incurred by the town in providing the service to the county users.”28 However, he concluded that a charge tied to taxes that would have been collected was improper, because there must be a “cost‐based relation between the charge imposed and the benefits conferred.”29 In an effort to address the Front Royal/Warren County situation, the General Assembly amended and reenacted Virginia Code provisions governing the rates and fees charged by localities for public water and sewer services.30 As a result of these legislative changes, any town within a 11,000 to 14,000 population bracket may now provide such services to industrial and commercial users outside its boundaries and collect “such compensation therefor as may be contracted for between the town and such user.”31 This special act apparently permits Front Royal to impose charges, with the agreement of the industry or business, that are not cost‐based. Thus, the town may indirectly collect sums beyond the actual “costs” that are equivalent to part or all of the taxes that would have been paid if the business had located within its boundaries. This indirect means of “sharing revenues” also has some benefit for the adjoining county because it does not have to share any of the county tax revenues it collects from the business. The Future Efforts in recent years to make it even easier for localities to use revenue sharing as part of their joint economic development plans have not been successful. In November 1998, two proposed constitutional amendments placed on the ballot sought to modify Virginia’s constitutional debt limitations. “Constitutional Amendment No. 4,” as it became known, provided for an amendment to Article VII, Section 10 of the Virginia Constitution to create an additional exemption from the debt limitations in that Section for contract obligations of localities to share revenues.32 In other words, it would have exempted counties from the referendum requirement and excluded such debt from the debt ceiling for cities and towns. The stated purpose of the proposal was to avoid the delay and uncertainties resulting from voter referenda which place Virginia localities at a competitive Disadvantage in courting new businesses. “Constitutional Amendment No. 3” provided for an amendment to Article VII, Section 2 of the Virginia Constitution, which would have also eliminated the debt restrictions in Article VII, Section 10, but would have also gone much further.33 The amendment would have authorized the General Assembly to provide by general or special act for the sharing of the costs of developing a “designated land area” and the tax revenue generated by the development. Such obligations to finance the development and to share the revenues would also not have been considered debt. This amendment would have also directed that, in any such legislation, the General Assembly shall provide for a special governing body for the development area whose members would be selected by the governing bodies of the participating localities. The legislature can grant the special governing body any power that can be exercised by the participating localities, including the power of 23 taxation. The apparent purpose of that provision was to permit a higher tax rate to be imposed on the industrial/commercial park, which revenues can be used for the expenses of providing the infrastructure to the site. Both amendments were defeated, however. Although proponents of the amendments argued that they were merely benign amendments to give Virginia localities more flexibility to compete for industry, opponents raised great concerns about unelected bodies having the power to tax and local governments creating a whole new category of debt not subject to voter approval. Despite these setbacks, revenue sharing agreements among localities in Virginia are likely to increase in the future as other localities see the rewards reaped by those already participating in such arrangements. Also, the General Assembly continues to be receptive to legislation that promotes cooperative action and therefore will likely support extending some of the existing special grants of authority to additional localities. Although greater use of revenue sharing Agreements will not guarantee growth and prosperity for all regions of the Commonwealth, they provide an excellent way for localities to commit to economic development projects that make the best use of a region’s available resources. Source: Virginia Lawyer, April, 2000. Endnotes: 1. 1979 Va. Acts, ch. 85, repealed by 1983 Va. Acts, ch. 523. 2. Va. Code §§ 15.2‐3400 to 15.2‐3401; Va. Code § 15.2‐1301. 3. Va. Code §§ 15.2‐6400 to 15.2‐6416; Va. Code §§ 15.2‐2119, 15.2‐2143. 4. See Va. Code §15.1‐1167.1. 5. 1990 Va. Acts ch. 62. 6. See Va. Code § 15.2‐3400. 7. 1986 Va. Acts ch. 333. 8. Va. Code § 15.2‐3400(3). 9. Va. Code § 15.23400(4). 10. Va. Code § 15.2‐3400(5). 11. Va. Code § 15.2‐3400(6). 12. The agreement was entered into pursuant to § 15.1‐1167.1, the predecessor statute of § 15.2‐3400. 13. 1990 Op. Atty. Gen. Va. 6. 14. The special fund exception provides that the constitutional debt limitations do not apply when payments are to be made solely from a specific fund derived from the revenues of a project. See Miller v. Watts, 215 Va. 836, 214 S.E.2d 165 (1975). 15. See 1984‐85 Va. Op. Atty. Gen. 96. 16. Ibid. 17. 1990 Op. Atty. Gen. Va. 6; see also 1988 Op. Atty. Gen. Va. 546 (“tax increment financing” by a county is subject to referendum requirement). 18. 1996 Va. Acts ch. 725. 19. Va. Code § 15.2‐1301(C). 20. Va. Code §§ 15.2‐6401 to 15.2‐6402. 21. Va. Code § 15.2‐6409. 22. The counties of Bland, Craig, Giles, Montgomery, Pulaski, Roanoke and Wythe, the cities of Roanoke, Radford and Salem, and the towns of Christiansburg, Dublin, Narrows, Pearisburg and Pulaski all joined to work together on joint industrial parks. 23. Va. Code § 15.2‐6406. 24. Va. Code § 15.2‐6407. 25. Va. Code § 15.2‐6406 26. See generally Concerned Residents of Gloucester County v. Board of Supervisors, 248 Va. 488, 449 S.E.2d 787 (1994) (supreme court declined to express an opinion as to the effect of a Code provision stating that certain waste disposal contracts “shall not be deemed to be a debt . . . within the meaning of any law . . . or debt limitation.”). 27. See Id. at 495, 449 S.E.2d at 792. 24 28. 1997 Va. AG LEXIS 99. 29. Id. 30. Va. Code §§ 15.2‐2119, 15.2‐2143. 31. Id. 32. 1998 Va. Acts ch. 587. 33. 1998 Va. Acts ch. 887. 25