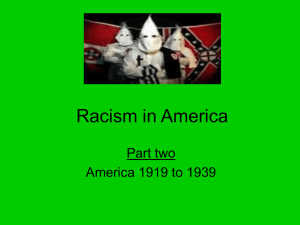

THE KU KLUX KLAN COMES TO KOWLEY KOUNTY, KANSAS: ITS

advertisement