the economic impact of seattle's music industry

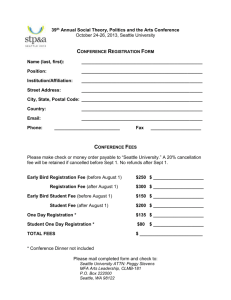

advertisement