here

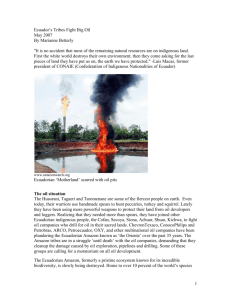

advertisement