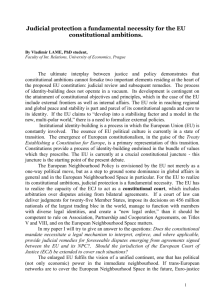

Individual Rights, Judicial Deference, and Administrative Law Norms

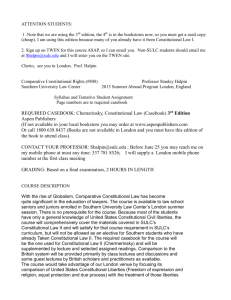

advertisement