Christina Rossetti

advertisement

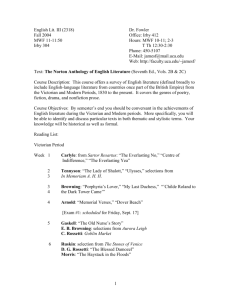

Christina Rossetti Possible Lines of Approach Rossetti as poet of gender and sexuality Rossetti as religious poet (Anglican or Tractarian) Rossetti as part of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood movement: A sister in the brotherhood (combined biographical and aesthetic approach) Rossetti’s social activism Rossetti’s marriage plots Rossetti’s “divided self” Family biographical readings Rossetti’s poetic craft Rossetti as “multimedia” poet Christina Rossetti and Dante Gabriel Rossetti Connection with other writers Notes on Approaching Particular Works Goblin Market “An Apple-Gathering” “Remember” “After Death” “Song” “A Birthday” “Monna Innominata” Questions for Discussion Critical Viewpoints/Reception History Appendix: Web Sources Possible Lines of Approach Rossetti as poet of gender and sexuality Most of Rossetti’s poems offer a critical lens on heterosexual relationships, specifically on women’s position in romance and courtship, and overall on the objectification of women. The poems also posit—most obviously, in Goblin Market—forms of female power within gender relationships and in larger cultural economies, such as the marketplace. Rossetti as religious poet (Anglican or Tractarian) With her elder sister Maria (who became an Anglican nun) and her Anglo-Italian mother Frances Polidori Rossetti, Rossetti was a devout Anglican who actively struggled to reconcile her engagement in the world, including human relations and the beauty of nature, with devotion to the divine. 1 Rossetti as part of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood movement: A sister in the brotherhood (combined biographical and aesthetic approach) Rossetti was not merely Dante Rossetti’s sister but also a close associate of the men (and some of the women) of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. She studied drawing with Ford Madox Brown and remained a writer whose concern for the relations of visuality and textuality mirrored that of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood movement. Her stylistic and thematic concerns (both with representing the visible world clearly and accurately, and with seeing the visible world as a conduit to the spiritual one) harmonized with the approaches of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. In fact, Lorraine Jansen Kooistra sees Rossetti’s illustrated books as fulfilling, in ways that none of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhoods did, their goal of creating illuminated texts that fully integrated word and image. Christina Rossetti and Dante Rossetti’s collaborations are a particularly interesting subject to focus on within the larger issue of Christina Rossetti’s relation to the movement. For example: • • • Christina Rossetti modeled for Dante Rossetti, notably as the Virgin Mary. Dante Rossetti illustrated Christina Rossetti’s work: as Christina Rossetti put it, “your protecting woodcuts help me to face my small public …” She was as pleased with his 1862 Goblin Market illustrations as she was dismayed by those by Laurence Housman for the 1893 edition of Goblin Market. Dante Rossetti advised Christina Rossetti regularly on her writing and publishing, providing her with the solidarity—especially on their collaborative work—to allow both of them to maintain artistic control over the final product. Teaching Christina Rossetti and Dante Rossetti together, as well as bringing in visuals from the Rossetti Archive and other online sources, may engage students’ interest in these relationships. Further, this approach allows instructors to introduce the collaborative context for many literary works that students would otherwise read as the products of isolated individuals. Finally, teaching the two siblings together can present a manageable and enjoyable way of integrating the textual and the visual literary and artistic movement in which paintings literally bear sonnets on their backs, and poems paint vivid pictures of landscapes both earthly and supernatural. Rossetti’s social activism Christina Rossetti was a regular contributor to the Tractarian journal of the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, but her contributions and concerns for the social problems of her time were hardly limited to religious issues. She wanted to go to the Crimea as one of Florence Nightingale’s nurses, but was rejected because of her youth. She volunteered at Highgate Penitentiary for fallen women, notably during the 1860s, the same time as she was writing Goblin Market, which has led some scholars (see, for example, Scott Rogers) to speculate that the women penitents were her intended audience. 2 Rossetti’s marriage plots Like Jane Austen, Rossetti has sometimes been pigeonholed in terms of failed engagements and ultimate spinsterhood. Rossetti’s first engagement, to painter and Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood James Collinson in the 1850s, fell apart because of his commitment to Roman Catholicism. In 1866, Christina Rossetti refused an offer of marriage from Dante translator and beloved family (and personal) friend Charles Cayley, purportedly because of his religious skepticism. Students may gravitate towards this aspect of the biography—as have critics before them—as a lens through which to read the poems, which are frequently focused on disjunctures within gender relationships. It is helpful to encourage them to think both with and beyond the biography. If they have been exposed to ideas about poetic personae elsewhere in the course (as they read Blake or Browning, for example), a reminder of the dangers of reading the persona as transparent to the author will be timely; if not, the case of Rossetti presents a great occasion for this discussion. It may be further useful to let them know that Rossetti and Cayley remained close friends after she rejected his proposal, and that when he died, he left her a small legacy, including a beautiful writing-desk, and made her his literary executrix. Rossetti’s “divided self” As Alison Chapman anatomizes in her “History, Hysteria, Histrionics: The Biographical Representation of Christina Rossetti” (Victorian Literature and Culture 24 (1998): 193-209), a powerful critical and biographical current until the late twentieth century was directed towards reading Rossetti as a divided poet and person, expressing rapture in the physical and sensory universe in her verse, but adamantly withdrawing from it in her life; a spinster, saint, hysteric, and/or invalid, “dead before death.” Rossetti’s recurrent ill health (Graves’ disease and later, the breast cancer that ultimately killed her) will further encourage students to read her as a recluse and “nun” figure and support the notion of repression, especially if they are put off by her religious devotion. It is now generally acknowledged that such readings inappropriately simplify both Rossetti and Victorian women as a whole, portraying them narrowly as repressed and oppressed by middleclass values and the patriarchy. Instructors can draw on the letters, photographs, and cartoons (specifically, “Christina Rossetti in a Tantrum”) to resist students’ urge to make Rossetti (and Victorian women) less complex than they were, and to consider that Rossetti might be devout and also playful, spiritual and also fond of jam, toffees, flowers, her young relatives, and trips to the zoo. Woolf’s essay “‘I am Christina Rossetti’” captures this play of opposites (although it tends toward a thesis of enigma and repression). 3 Family biographical readings As well as participants in a literary/artistic “circle” (like the Wordsworth circle or the Byron/Shelley circle—both groups that students may have encountered in other courses or earlier in a British Literature survey), the Rossettis were an intensely creative family, whose productivity may have been incrementally increased by continual collaborations among the children. In this regard, they may be compared to the Brontës, another family that students may have encountered. While Dante and Christina Rossetti were the best known of the group, Maria was a Dante scholar and William Michael, who not only edited his siblings’ works and letters but also wrote memoirs of them, was also a prolific writer on his own behalf. The question of family creative relations may be an interesting one for students to pursue independently. Rossetti’s poetic craft • • • • Christina Rossetti’s intentional allusiveness (Plato, the Bible, Dante, Petrarch). Particularly useful in this regard is Anthony Harrison’s book Christina Rossetti in Context (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1998), especially chapters 4 and 5, which address allusions to Plato, Augustine, Dante, and Petrarch. Rossetti’s work with the sonnet form and sonnet sequence (“Monna Innominata”). Useful for purposes of comparison may be the work of Elizabeth Barrett Browning (for a discussion, see the Elizabeth Barrett Browning chapter of this Instructor’s Guide). Goblin Market and irregular meter/line. The catalogue and/or simile string (“A Birthday”; Goblin Market). Both poems are useful for teaching metaphor; Goblin Market is also particularly useful for inviting more complex analyses of how metaphors build an associative fabric over an entire long poem. Rossetti as “multimedia” poet • While Christina Rossetti never published her own illustrations to her work, the texts’ appeal to visual artists resulted in more than one request to illustrate them. In addition, composers set many of her poems to music; the best-known example may be Holst’s accompaniment to “In the Bleak Midwinter,” included in the Pilgrim and other hymnals. Students may enjoy listening to this enactment of lyric poetry—and it of course provides an opportunity to remind them of the original meaning of the term. Christina Rossetti and Dante Gabriel Rossetti Interesting points of comparison may include: • Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s “The Blessed Damozel” with Christina Rossetti’s poems that reach beyond the grave (“Remember,” “After Death,” “Song”). • Christina Rossetti’s “In an Artist’s Studio” with excerpts from Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s “Jenny” and/or with Dante Rossetti’s portraits of women, especially Lizzie Siddall. 4 • Dante Rossetti’s painting-poem pairs (such as The Blessed Damozel/The Blessed Damozel, or Body’s Beauty/Lady Lilith), with Goblin Market and its illustrations. Connection with other writers • • • • • • • Christina Rossetti and Elizabeth Barrett Browning: Representations of gender/love relationships and different use of sonnet form and its associations with romantic conventions. Paired women in Goblin Market and Coleridge’s “Christabel.” Goblin Market and Shelley’s “To a Skylark” (simile strings). Goblin Market and Hopkins’s “Spring and Fall” (themes of innocence and experience). Rossetti’s poems on relations across the grave with selections from Tennyson’s In Memoriam: secular/sacred love and how it may be negotiated in different ways. Rossetti’s representations of heterosexual courtship plots and miseries, and women’s subjectivity in them, compared/contrasted to woman seen from outside in Tennyson’s “Mariana” or, looking earlier, Keats’s “La Belle Dame Sans Merci.” Homosocial relations/desire in Goblin Market, Coleridge’s “Christabel,” and Tennyson’s In Memoriam: plusses and minuses of queer readings; see Carroll Smith-Rosenberg’s essay “The Female World of Love and Ritual” (in Disorderly Conduct: Visions of Gender in Victorian America [New York: Oxford University Press, 1985]). Notes on Approaching Particular Works Goblin Market Form: long narrative poem with lines of irregular length and meter. Rossetti’s most frequently taught work, and the one that has catalyzed the most critical scholarship, Goblin Market invites a seemingly inexhaustible range of critical approaches. One debate is whether to read the poem literally or allegorically. Should goblins, fruit, desire, suffering, and redemption be read as all representative of larger issues such as sexual temptation and desire, drug addiction and its consequences, and the overall vanity of the physical world? Or can we read the fruit as actual fruit and the market as an actual market? Critics working from both of these directions have variously theorized Rossetti’s purposes as: • advocating communities of women without men • warning against the damages of temptation and desire in general • warning against extramarital sexuality and fallenness • rewriting the Miltonic “bogey” (as Gilbert and Gubar named it) of Paradise Lost and/or Christian theology, in part by creating female Christ-figures and heroines who can save themselves • expressing alternative/feminist forms of desire, from lesbian eros to the desire for power within a male-constructed marketplace that includes not only goods from around the British empire, but also women themselves 5 • • exploring various “Others” through the representation of goblin men as human/animal hybrids: sexual adult males; racialized Others of the British empire critiquing the literal marketplace, particularly a marketplace that drew on the entire British empire, and women’s growing place as consumers. One of the challenges of a poem this generative is to encourage students to build thoughtful analyses with textual evidence while resisting the impulse to try to pin down the poem too firmly or reductively. Genre: The poem actively draws on at least two genres that combine entertainment and didacticism—the fairy/folk tale and the parable. Twins as a Formal Element: The formal element of the paired or twinned sisters, emphasized by Dante Rossetti’s woodcut, exemplifies and then disrupts a recurrent literary pattern of “twinning.” It is interesting to compare Rossetti’s use of two women as foils for each other to other such uses. This may be done both in texts that may be familiar to students, such as fairy tales (Snow White and Rose Red), and in canonical and non-canonical texts they may have read in the British Literature survey, from Una and Duessa in Spenser’s Faerie Queen, to Shakespeare’s many twin plots, to Rebecca and Rowena in Scott’s Ivanhoe, to Christabel and Geraldine in Coleridge’s “Christabel,” to LeFanu’s Carmilla. The twins seem, both in Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s illustrations and in the poem’s description of them, to be nearly identical. The effect of such twinning will be something students are in part familiar with from other cultural representations; “evil twin” plots are a staple of popular culture. With the convention firmly in mind, as well as how it may be used, it may be good to ask what does Rossetti do with it? Also, how does Rossetti triple the convention? (Compare Lizzie, Laura, and Jeanie.) Rossetti’s twins invoke two different ideas about women predominant in the nineteenth century: the “angel in the house” and the “natural” woman. The angel in the house (see Coventry Patmore): • moral beacon—elevates others • spiritual rather than sensual • passionless except for her maternal qualities • spirit rather than body • usually a middle-class figure. The natural woman • variously figured as primitive/savage, animal, sensual, emotional, sexual, monstrous • all body and emotion: physically and emotionally responsive • pre-logical, irrational • childlike • usually a working-1.class figure 6 It is clearly difficult to reconcile the two ideas about women. Many Victorian texts in effect compartmentalize the two, placing everything on the first list in one character, and everything on the second list in another, thus neatly keeping them apart. Often the “animal” woman comes to a bad end. In Lizzie, Rossetti draws a somewhat representative “angel in the house,” at least until the end; in Laura, she gives us a modified version of the natural woman. But while in other texts the “animal” woman functions as a scapegoat or whipping girl and is regularly expelled from the text through death, etc., in Goblin Market both sisters are given a happy ending, complete with marriage and motherhood. Further, because Lizzie becomes a venturesome, heroic figure at the end—and enjoys it—“Laura, make much of me!”—she moves out of our expectations for an angel in the house. The twin golden heads, which at the start might have emphasized the sisters’ character differences in contrast to their physical sameness, at the end are borne out as markers of two women who, through the courage of one, can have similar outcomes. (If Rossetti wanted to entirely emphasize their differences, one would think she would have left Laura’s hair gray.) Style: The initial appeal of the catalogues of pleasing and concrete sensory details of fruit positions the reader in a similar relationship to the fruit as the sisters: surprised, overcome by the sheer abundance and variety, and attracted. The two are described together in lines 184-191: Golden head by golden head, Like two pigeons in one nest Folded in each other's wings, They lay down in their curtained bed: Like two blossoms on one stem, Like two flakes of new-fall’n snow, Like two wands of ivory Tipped with gold for awful kings. Laura is described alone in lines 81-85, and again in lines 495-502: Laura stretched her gleaming neck Like a rush-imbedded swan, Like a lily from the beck, Like a moonlit poplar branch, Like a vessel at the launch When its last restraint is gone. …. Writhing as one possessed … Her locks streamed like the torch Borne by a racer at full speed, Or like the mane of horses in their flight, 7 Or like an eagle when she stems the light Straight toward the sun, Or like a caged thing freed, Or like a flying flag when armies run. Lizzie, in contrast, is described in this string of similes in 407-420: White and golden Lizzie stood, Like a lily in a flood,— Like a rock of blue-veined stone Lashed by tides obstreperously,— Like a beacon left alone In a hoary roaring sea, Sending up a golden fire,— Like a fruit-crowned orange-tree White with blossoms honey-sweet Sore beset by wasp and bee,— Like a royal virgin town Topped with gilded dome and spire Close beleaguered by a fleet Mad to tug her standard down. The content of the metaphors—nautical, military, natural, etc.—builds over the course of the poem, creating a landscape that consistently underpins the denotative one. Themes of Gender and Sexuality: A poem in which both of the females are maidens and all the males are goblins obviously invites multiple analyses on the basis of gender and sexuality. Many readers see a buried, occulted, or spectral lesbianism in this poem. What do we do with this? For one, we can compare it to the more openly claimed and affirmed lesbian sexuality of the poetry of Michael Field. How are they alike? How different? We should also not forget the dangers of anachronistic thinking (there was no such category as “lesbianism” until later in the century; furthermore, the conventions of same-sex relationships were quite different in the Victorian era; see Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, “The Female World of Love and Ritual,” in her book Disorderly Conduct). Ask students to try to describe the relationship between Laura and Lizzie without ever using the key words “homoerotic” or “lesbian.” This will force them to articulate the relationship qualitatively rather than through convenient labels. Religious Themes: A poem in which fruit is the source of prohibition, desire, and suffering is surely an allusion to Genesis; however, Rossetti’s references to Genesis are not always straightforward. The forbidden fruit (“We must not look at goblin men, / We must not buy their fruits:”) is sweet only initially, with an aftermath of sorrow: this much is consistent with Genesis. However, in Genesis the punishment for eating forbidden fruit is to be sent out of Eden and into the world to labor and suffer, and Rossetti’s poem does not follow that narrative. There is no change of location; the only major transformation that occurs is the loss of the ability to hear and 8 see the goblin men—and of the pleasure that sensory awareness engenders. The poem also fails to match Milton’s collapsing of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament in Paradise Lost, where a sacrifice brings redemption from death. In Rossetti’s poem, the hero is not Christ but Lizzie, who becomes the redemptive fruit, returning after her beating by the goblin men to ask her sister to Hug me, kiss me, suck my juices Squeezed from goblin fruits for you, Goblin pulp and goblin dew. Eat me, drink me, love me; Laura, make much of me: For your sake I have braved the glen And had to do with goblin merchant men. In its most literal terms, then, what saves and redeems Laura is not Christ, but her sister Lizzie. As the moral of the story reminds us, “there is no friend like a sister.” Lizzie may indeed be imitating Christ, but the pleasures the poem attributes to her—and they are clear—are not simply of sacrifice but of action, agency, and control. When Laura is “at death’s door,” … Lizzie weighed no more Better and worse; But put a silver penny in her purse, Kissed Laura, crossed the heath with clumps of furze At twilight, halted by the brook: And for the first time in her life Began to listen and look. Returning home covered with fruit, Lizzie experiences the pleasure of not having participated in the market with her hair, tears, or desires—or even her money. She … heard her penny jingle Bouncing in her purse,— Its bounce was music to her ear. Further, Lizzie’s prioritizing action and love over moral reflection brings the same kind of pleasure Laura experienced, that of experience: listening and looking, which is not by definition sinful in the poem. Giving up oneself for the wrong reasons, and in service to another’s desires, may be the problem. For Rossetti, as for Blake before her, the key opposition is innocence and experience, not innocence and guilt. No simplistic explanation of the poem as a religious allegory, then, really fits. 9 There are a number of useful critical texts that explore the challenge of how to read the devotional messages in Goblin Market—particularly in context of Christian theology, Tractarianism, and gender conventions, and how to address the erotic and even homoerotic message that seems intertwined with it. These include • • • • Diane D’Amico, Christina Rossetti: Faith, Gender, and Time (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1999). Mary Arseneau's article “Incarnation and Interpretation: Christina Rossetti, the Oxford Movement, and Goblin Market” (Victorian Poetry 31 [1993]: 79-93) Mary Wilson Carpenter, “‘Eat Me, Drink Me, Love Me’: The Consumable Female Body in Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market,” Victorian Poetry 29 (1991), argues that Rossetti produces “a uniquely feminocentric view of women’s sexuality” where “salvation is to be found not in controlling [female] appetite but in turning to another woman” (417). MaryLu Hill’s provocative “‘Eat Me, Drink Me, Love Me’: Eucharist and the Erotic Body in Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market” (Victorian Poetry 43.4 [2005]: 455-72) argues for the necessary integration of the devotional and erotic readings of the poem, and particularly of the scene of Lizzie’s return. According to Hill, The amazing quality of Goblin Market is that it allows the seemingly contradictory forces of sexuality and spirituality to co-exist in a mutually beneficial manner. By resisting the impulse to reduce these forces to an either/or configuration, and by letting the imagery of the Eucharist’s physical and spiritual realities speak for themselves, Rossetti offers a masterful illustration of how the forces of the erotic and the spiritual might be yoked together to reveal the body as something desirable yet also the very stuff of sacrifice and redemption. As such, only by reading Goblin Market with an eye to both the sensual and the spiritual can we understand the nuances of Rossetti’s sophisticated yet concrete vision of the subtleties of the Eucharistic mystery. (p. 470) • See also Lynda Palazzo, Christina Rossetti’s Feminist Theology (New York: Palgrave, 2002). Economic Themes: The fact that the story takes place in relation to a market continues to generate exciting new critical readings, whether we read the market as metaphorical, literal, or both. Key critical texts include: • • Elizabeth K. Helsinger’s “Consumer Power and the Utopia of Desire: Christina Rossetti’s ‘Goblin Market’,” in Victorian Women Poets: Emily Bronte, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Christina Rossetti, ed. Joseph Bristow (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995), 189-222. Terrence Holt, “‘Men sell not such in any town’: Exchange in Goblin Market,” Victorian Poetry 28.1 (1990): 51-67. Victor Roman Mendoza argues persuasively in “‘Come Buy’: The Crossing of Sexual and Consumer Desire in Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market” (ELH 73.4 [2006]: 913-947) that “the poem’s language of economics as well as its economics of language rehearse a form of desire and a mode of enjoyment based on self-negation.” Mendoza references William Michael 10 Rossetti’s oft-quoted description of his sister’s poetry as “replete with the spirit of selfpostponement” and suggests that the points of pleasure for the speaker of the poem are at “the very moments of self-denial during the erotic exchanges at market. Ultimately, if Rossetti intended that the poem be read as a critical renunciation of capitalist commerce and sexuality, as critics have suggested, then we must consider that it is that very act of renunciation that allows for the text's own production—and enjoyment—in the first place.” Krista Lysack’s “Goblin Markets: Victorian Women Shoppers at Liberty’s Oriental Bazaar” (Nineteenth-Century Contexts 27.2 [June 2005], 139-165) contributes an important focus on the imperial layers in Rossetti’s marketplace critique. Lingering questions Goblins and Animals: Rossetti’s love of animals, shared with her brother Dante Rossetti (famous for his household menagerie), is well documented in her letters, which tell of visits to the zoo and advocate anti-vivisectionism to her friend Mrs. Heiman. Virginia Woolf writes that Christina Rossetti “loved the ‘obtuse and furry’—the wombats, toads, and mice of the earth—and called Charles Cayley ‘my blindest buzzard, my special mole.’” Do these facts problematize readings of the human-animal hybridity of the goblin men as a sign of their badness? In other words, what does animality have to do with being a goblin? Note that while Lizzie and Laura are repeatedly compared to animals through similes, they are not hybridized. Audience(s): Christina Rossetti wrote for both adults and for children. Goblin Market, however, was clearly not directed at a child audience, as Lorraine Janzen Kooistra has documented. All the same, the poem has presented a classification challenge for readers, as demonstrated by the fact that some later scholars labelled it as Victorian children’s fantasy, a phenomenon that Kooistra anatomizes in her book (Christina Rossetti and Illustration: A Publishing History [Athens: Ohio University Press, 2002]). As she notes, the combination of fairy-tale conventions and illustrations are habitually read in the twentieth century as signaling a child audience. Students may be fascinated and troubled by their own sense that the text offers mixed signals and suggests the hard-to-reconcile combination of a putative child audience with sensual imagery and possibly homoerotic themes. This makes for a rich discussion focus. “An Apple-Gathering” Form: Quatrains of iambic pentameter (lines 1-3) and trimeter (4). As in Goblin Market, “Song” (“She sat and sang …”) and other works, Rossetti looks not only at a single persona but at women’s various experiences across a narrowly defined range. Disappointment is the outcome for all three in “Triad,” just as both song and tears result in silence at the end of “Song.” Students may productively consider what the effect is of including more than one woman in these poems. “An Apple-Gathering’s” setting, use of fruit, and tone may remind students of Goblin Market. 11 “Remember” Form: Sonnet, rhymed abba abba cddece. “After Death” Form: Sonnet, rhymed abba abba cdeedc. “Song” Form: Lyric. All three poems speak from a position beyond the grave. Angela Leighton argues that Rossetti’s poems about being dead are not “suicide notes”; neither are they imaginary deferrals of poetic fame toward a more receptive posterity. Instead, they are poems about being dead as a condition for speaking at all. They do not express a memento mori at all, and they offer few traditional warnings about saving or wasting time. Instead, they play with time, jokingly, absurdly. Being dead allows the speaker to be in and out of time, to be now and then, which is Rossetti’s favorite lyrical place. “When I am dead, my dearest” thus pitches, with idiomatic ease, an imaginary then into now, when “I am.” It sets out to puzzle the historical imagination, to confuse rather than measure time. In it, the future is foreshortened into a present which then goes on. In a sense, this mimes what all lyrics do: they make time their own, which is the time in which they simply “Sing” (Angela Leighton, “In Time, and Out: Women's Poetry and Literary History,” Modern Language Quarterly 65.1 [2004]: 131-148). “A Birthday” Form: Lyric. Meter: stanza 1, iambic tetrameter; stanza 2, anapests followed by trochees. Compare “A Birthday” to “Song of Solomon.” Like Goblin Market and “Triad,” this poem provides a useful text for discussing metaphor. “Monna Innominata” Form: Christina Rossetti calls this poem a “Sonnet of Sonnets”: a sequence of 14 sonnets, most beginning abba abba followed by irregular combinations for the sestet. Sonnet 14, for example, has the following scheme: abba acac dce ecd. Backgrounds: Rossetti’s prefatory note makes it clear that the sonnet sequence is spoken by the persona of an imagined “unnamed lady” who might have preceded Laura and Beatrice, and who differed from them in “sharing her lover’s poetic aptitude.” She connects her project to her admired contemporary Elizabeth Barrett Browning, speculating that this is the sonnet sequence “the Great Poetess of our own day and nation” might have written had she been “unhappy instead of happy.” William Rossetti, however, states in his memoir that “[i]t is indisputable that the real veritable speaker in those sonnets is Christina herself, giving expression to her love for Charles Cayley.” The question of the relationship between the persona and the poet, as well as more generally of the multiple voices in the sequence (which include, of course, the epigraphs from Dante and Petrarch that begin each sonnet), is explored by many critics; see Billone for a useful overview. 12 Without privileging either the poet or her brother as offering the “authoritative” position on the sonnet sequence, students can be invited to consider a both/and approach. They will find it useful to know that Cayley and Christina Rossetti remained close friends until his death. Useful critical works include: • Amy Billone, Little Songs: Women, Silence, and the Nineteenth-Century Sonnet (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2007). • Sharon Bickle, “A Woman of Women for ‘A Sonnet of Sonnets’: Exploring Female Subjectivity in Christina Rossetti’s ‘Monna Innominata’,” in Tradition and the Poetics of Self in Nineteenth-Century Women’s Poetry, ed. Barbara Garlick (New York: Editions Rodopi B.V., 2002). • Alison Chapman, “Sonnet and Sonnet Sequence,” in A Companion to Victorian Poetry, eds. Richard Cronin, Antony H. Harrison, and Alison Chapman (Blackwell, 2002). • Marjorie Stone, “‘Monna Innominata’ and Sonnets from the Portuguese: Sonnet Traditions and Spiritual Trajectories,” in The Culture of Christina Rossetti: Female Poetics and Victorian Contexts, eds. Mary Arseneau et al. (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1999). Questions for Discussion 1. In Goblin Market, pay close attention to who can hear and see the goblin men and who cannot at different points in the poem. What logic seems to be behind this? What controls who can sense them and who cannot? 2. What seem to be the rules of the fruit in Goblin Market? How do you buy it? Where can you eat it? How does eating it make you feel? How do these things change as the poem progresses, and how might we explain the changes? 3. In Goblin Market, what are the terms on which the goblin marketplace operates? How does one buy the fruit? What different goods or benefits do Laura, Jeannie, and Lizzie want to get from it? Compare Lizzie’s encounter with the goblin men to Laura’s. 4. At various places in Goblin Market, Rossetti uses a string of similes to describe the sisters. How do the similes develop the sisters as distinct characters and elaborate the theme of the poem? 5. Two significant purposes of works of art are to educate (often morally) and to entertain. What is the balance between didacticism and pleasure in Goblin Market? What do you think the poem wants the reader to learn, and how? What do we learn—and how? 6. The tone of “Remember,” “After Death,” and “Song” (“When I Am Dead”) is ambiguous. Is the speaker bitterly ironic or sincere? How can we tell? 7. Compare the overall exploration of love in “Monna Innominata” to that in Sonnets from the Portuguese. 13 8. Rossetti’s prefatory note to “Monna Innominata” speculates about how Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s sonnets would be different had she herself not been happy, thus equating the persona in Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s work with the author. In what ways does Rossetti resist such identification herself, despite her brother’s insistence that the transparency is there? Critical Viewpoints/Reception History Review of Goblin Market and Other Poems. British Quarterly Review 36 (July 1862): 230-31. Mrs. Charles Eliot Norton, “‘The Angel in the House’ and ‘The Goblin Market,’” Macmillans Magazine 8 (September 1863): 398-404. Mrs. Charles Eliot Norton, “Miss Rossetti’s Poems,” The Nation 3 (19 July 1866): 47-48. Edmund Gosse, “Christina Rossetti.” Century Magazine 46 (June 1893): 211-17. Virginia Woolf, “‘I am Christina Rossetti,’” from The Common Reader, Second Series (1932). NB. This essay is now in the public domain in Canada, where this website originates, but remains in copyright in many other jurisdictions, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. If you are teaching in a jurisdiction where a work is in copyright, please be aware that you may be obliged to obtain permission from copyright holders as a condition of photocopying material for students or otherwise reproducing the material. Rossetti was well-received by her contemporaries, as Norton and Gosse demonstrate, and throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth she garners exceptionally high praise from other poets. Gerard Manley Hopkins writes (in a letter to his mother, dated 5 March 1872) that “Miss Christina … has been, I am afraid, thrown rather into the shade by her brother … but for pathos and pure beauty of her work I do not think he is her equal: in fact the simple beauty of her work cannot be matched” (3). The novelist and Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood descendant Ford Madox Ford, similarly, saw her as “downtrodden by roaring Victorians” and championed her in comparison to Dante Gabriel, as recorded by Ezra Pound in a series of his letters to Olivia Rossetti Agresti, William Michael’s daughter: not that F[ord] ever did any harm to Dante Gabe’s glory, but that [he] adored Christina’s way of writing/and was furious with the greater attention given the jewels and velvet. In fact the lucidity and clarity of English verse today (when it has any) comes very largely from Ford’s ranting about Christina [illegible deletion] and the kind of simplicity of language he found in some of her verse, which did NOT hit the front page in the Swinburne plus ’90 furores, or twilit Celts…. Fordie … used to stomp round insisting, and quoting her in inaudible voice. (I Cease Not to Yowl: Ezra Pound’s letters to Olivia Rossetti Agresti [Virginia, 1997], 28-9; 182) 14 In the twentieth century, Woolf’s essay excepted, Rossetti criticism was mostly dormant until second-wave feminist criticism in the 1970s reinvigorated interest in her. Feminist literary critics, notably Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar (The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination [New Haven: Yale UP, 1979]) and Margaret Homans reclaimed Rossetti as one of those nineteenth-century women writers who struggled with “Milton’s Bogey.” They locate alternate modes of cultural power in her poetry that work against the combined repressions of the patriarchy and Victorian culture at large. Since then, both the criticism and the biography of Rossetti have continued to explore new areas of her life, contexts, literary relations, and poetics. Anthony Harrison’s study, Christina Rossetti in Context (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1988), counters an approach to Rossetti as a spontaneous or instinctive poet with a detailed exposition of how she used and developed her extensive literary training and awareness of textual precedents, working consciously and in sophisticated ways with earlier scriptural, philosophic, and poetic traditions. Mary Arseneau’s Recovering Christina Rossetti: Female Community and Incarnational Poetics (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004) emphasizes the need to read Rossetti in two heretofore overshadowed contexts: the community of single women (both in her family and in her church relations) that formed a significant and consistent element of her life, and Tractarian aesthetics. For example, she reads Goblin Market more in terms of the influence of Rossetti women (Frances and Maria) than in terms of Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Rossetti men William and Dante Gabriel, and explores the poem’s use of figurative language as expressive of Anglo-Catholic ideologies of nature and art, particularly in terms of the purpose of creating awareness and growth in the reader. Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, in Christina Rossetti and Illustration: A Publishing History (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2002), adds a significant layer to exploration of Rossetti both as individual writer, collaborator and colleague, and as “commodity” repackaged over time. Her ideas are especially useful for exploring the issue of Rossetti’s audience and the status of Goblen Market as literature for adults or children. Appendix: Web Sources The Victorian Web: http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/crossetti/index.html The Rossetti Archive: http://www.rossettiarchive.org/ The publisher gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Martha Stoddard-Holmes of California State University, San Marcos, for the preparation of the draft material. 15