Caught in the (One-)Act: Staging Sex in Late Medieval French Farce

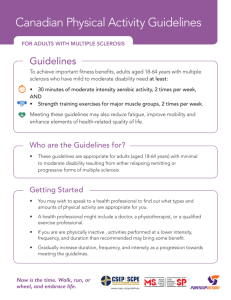

advertisement