Volume 75, No. 1 Spring 2012 - Mississippi Library Association

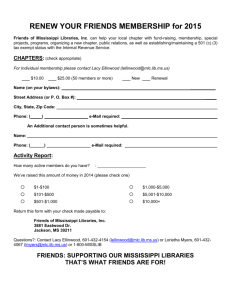

advertisement