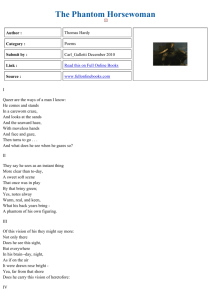

The Position of Women in Thomas Hardy's Poetry

advertisement